The following is reproduced by permission and with the generosity of the author from William Dalrymple’s The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty: Delhi, 1857. I’ve mentioned this brilliant book in a previous post: Favorite Blogs: The Delhi Wallah. These are from the gripping few pages where Dalrymple describes the irrational and totally vengeful destruction of much of Delhi by the British after the Uprising of 1857 had been suppressed.

The entrance to the Jama Masjid

*******************************************************************************************************************************************

Canning had already given orders to destroy the Delhi walls and defences, but Lawrence managed to get the orders rescinded, arguing that there was insufficient gunpowder in Delhi to blow up several miles of walls. By the end of 1859, Canning had agreed to his plan only to demolish what was needed to make the fort and city more defensible. By 1863, the planned demolition of the eastern half of Chandni Chowk down to the Dariba had also been stopped. Even so, great swathes of the city – especially around the Red Fort – were still cleared away, as Ghalib recorded in a series of sad letters to his correspondents across Hindustan: “The area between Raj Ghat [on the city’s eastern edge, facing the Yamuna] and the Jama Masjid is without exaggeration a great mound of bricks.”

“The Raj Ghat Gate has been filled in. Only the niched battlements of the walls is apparent. The rest has been filled up with debris. For the preparation of the metalled road, a wide open ground has been made between Calcutta Gate and the Kabul Gate. Punjabi Katra, Dhobiwara, Ramji Ganj, Sadat Khan ka Katra, the Haveli [palace, mansion, konak] of Mubarak Begum [Ochterlony’s widow], the Haveli of Sahib Ram and his garden – all have been destroyed beyond recognition.”

What had been the neighborhood around the Jama Masjid (above). The Kashmiri Gate (below).

Other letters of Ghalib’s mourned the destruction of some of the city’s finest mosques, such as the Akbarabadi Masjid and the great Masjid Kashmiri Katra [I haven’t been able to find any photos of these, but the Akbarabadi Masjid was considered a sort of twin to the Jama Masjid — my comment]; great Sufi shrines such as that of Sheikh Kalimullah Jahanabadi;* the imambara+ built by Maulvi Muhannad Baqar; and the establishment of a cleared open space 70 yards wide around the Jama Masjid. Four of Delhi’s most magnificent palaces were also completely destroyed; the havelis of the recently hanged nawabs of Jhajjar, Bahadurgarh and Farrucknagar, as well as that of the Raja of Ballabargh. The great caravanserai of Shah Jahan’s daughter Jahanara was demolished and replaced by a new town hall. Shalimar Bagh, where Aurangzeb had been crowned, was sold off for agricultural use. Even where old Mughal structures were allowed to continue, they were often renamed: Begum Bagh, for example, became the Queen’s Gardens.

Tragically the Red Fort was another area where Lawrence intervened too late to stop the wholesale destruction. He managed to save both the Jama Masjid and the Palace walls, but 80 per cent of the rest of the Fort was leveled. Harriet Tyler, who was living in an apartment above the Diwan i-Am at this time, was horrified by the decision and decided to paint a panorama of the city before it disappeared. It confirmed her in her disgust of the way the British had behaved in Delhi since the assault began on 14 September. “Delhi was now truly a city of the dead,” she wrote in her memoirs. “The death-like silence of that Delhi was appalling. All you could see were empty houses… The utter stillness…[was] indescribably sad. It seemed as if something had gone out of our lives.”

[These are some drawings I’ve been able to find of the palace and palace grounds but, though beautiful, they don’t give you much of a sense of what was destroyed — my comment]:

(the above appears in Dalrymple’s book)

The demolitions started at the Queen’s Baths in November 1857, and continued through most of the Palace, destroying an area “twice the area of the Escorial,” as the horrified historian James Ferguson pointed out twenty years later. “The whole of the area between the central range of the buildings south and eastwards from the bazaar, measuring about 1000 feet each way, was occupied by the harem apartments – twice the area of any Palace in Europe.”

“According to the native plan I possess, which I see no reason for distrusting, it contained three garden courts, and some thirteen or fourteen other courts, arranged some for state, some for convenience; but what they were like we have no means of knowing. Not one vestige of them now remains… The whole of the harem courts of the palace were swept off the face of the earth to make way for a hideous British barrack, without those who carried out this fearful piece of vandalism, thinking it even worthwhile to make a plan of what they were destroying or preserving any record of the most splendid palace in the world.”

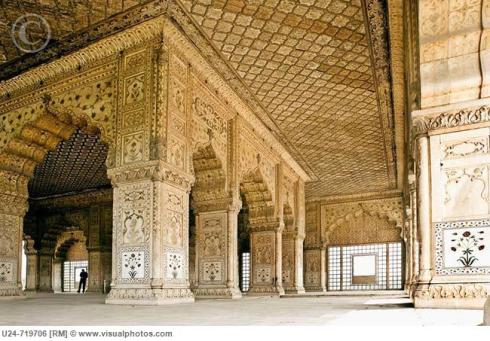

As late as March 1859 George Wagentrieber was please to record in the Delhi Gazette that “a good deal of blowing up” was still going on in the Palace. Some of the finest buildings were the first to go, such as the Chhota Rang Mahal. Even the Fort’s glorious gardens – notably Hayat Bakhsh Bagh and Mehtab Bagh – were swept away. All that was left by the end of the year was about one-fifth of the original fabric – principally a few scattered, isolated marble buildings strung out along the Yamuna waterfront. These were saved owing largely to the fact that they were in use as offices and messes by the British occupation troops, but their architectural logic was completely lost once they were shorn of the courtyards of which they were originally a part.

(click on this photo)

All the gilded domes and most of the detachable marble fittings were stripped and sold off by the Prize agents. As Fergusson noted,

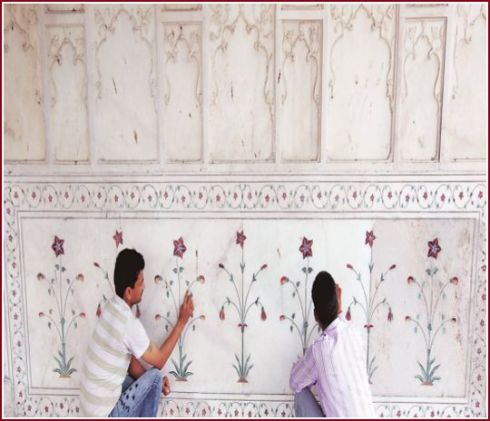

“when we took possession of the palace, everyone seems to have looted after the most independent fashion. Among others, a Captain (afterwards Sir) John Jones [who had blown in the Lahore Gate during the capture of the Fort] tore up a great part, but had the happy idea to get his loot in marble as table tops. Two of these he brought home and sold to the Government for 500 pounds, and were placed in the India Museum.”

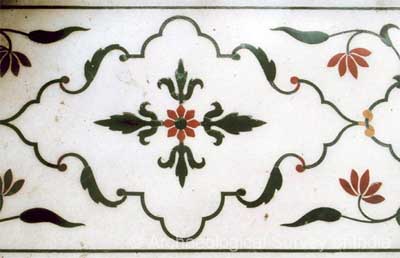

These fragments included the rightly celebrated “Orpheus panel” of pietra dura inlay which Shah Jahan had placed behind his Peacock Throne.

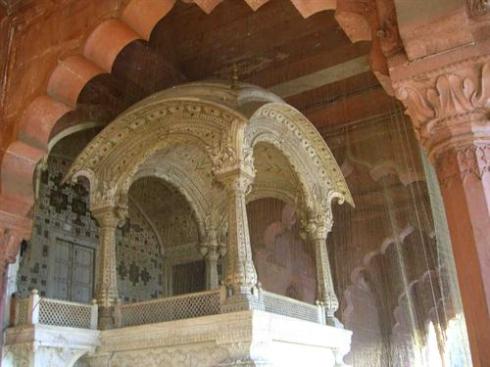

Meanwhile, what remained of the Mughal’s Red Fort became a grey British barracks. The Naqqar Khana, where drums and trumpets had once announced the arrival of ambassadors from Isfahan and Constantinople, became the quarters of a British staff sergeant. The Diwan i-Am became a became a lounge for officers, the Emperor’s private entrance a canteen, and the Rang Mahal was turned into a military prison. The magnificent Lahore Darwaza was renamed the Victoria Gate and became “a bazaar for the benefit of the Fort’s European soldiers.” Zafar’s contribution to the Palace architecture – the Zafar Mahal, a delicate floating pavilion in a large red sandstone tank – became the centerpiece of a swimming pool for officers, while the surviving pavilions of Hayat Bakhsh Bagh were turned into urinals.

* A modest tomb of the saint is, however, still extant in the Pigeon-seller’s Bazaar in Old Delhi

+ Shia religious hall used to hold mourning ceremonies during Muharram

******************************************************************************************************************************************

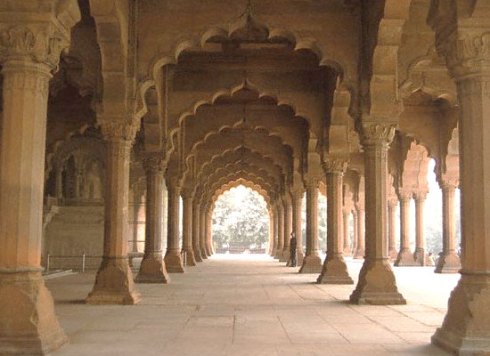

Below, I’m just posting whatever photos I can find of what’s left of the palace, without specific naming of each building, but hoping that readers constantly keep in mind that all this gorgeousness — and seen here damaged and stripped of its jewelled furnishings, gold, carpets, silken hangings, “Dacca gauzes,” running waters and the exquisitely dressed men and women of the court — is only the twenty percent of the original that survived. Some photos may be clickable:

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

My dear Nicholas, delighted to find someone from another ‘corner’ of the globe, sharing our concerns. Your passion for Delhi far exceeds that of most of us Delhiwallas..were you a Delhiwalla in a previous incarnation in those times? Mirza Ghalib?! I stumbled into your blog looking for contexts from Last Mughal, when I was writing on destruction of human heritage on my site http://www.indrayanikaathi.com..using some of your excellent snaps, hope you will not mind…

Very interesting. Good read.