The Valley of Dropoli, the pass up to the Pogoni plateau near Libochovo, and in the distance, the snowcapped peaks of Nemerčka, from the Monastery of the Taxiarches in Derviçani, Easter 2014 (click)

When my father used to say “ta mere mas” (literally “our parts”) he was referring to the thirty or so Greek-speaking villages in the valley (shown above) and surrounding mountains of southern Albania where he grew up. It was a term that, before I had gotten too deep into my childhood, before I could even name those places, I had understood instinctively, almost oppressively. I knew who these people from our parts were, these landsmen, exotic even to me in certain ways. I knew how they comported themselves, knew their body postures; I knew how they spoke, how they treated a guest. I knew how they danced, how they sang; I knew their weird, haunting music before I could articulate why it stirred me so deeply. I knew how they prayed; I knew how they grieved. They didn’t laugh much. Or smile easily.

Later, in graduate school, students from Greece, the Balkans, Turkey, Iran, the Arab Middle East and even South Asia seemed to instinctively gravitate towards one another, and not just because they were all working in the history or the politics of the area but, well, mostly because we partied well together. I started using my father’s “our parts” semi-ironically, a little guiltily as well because it was without the Appalachian tone of mystery with which he used it, to indicate the region that all of us were somehow connected to – the region that, however vast and varied, and where, however viciously we treated each other in past and present — seemed to bring us together in an automatic comfort and feeling of ease. The term inevitably caught on and without irony. I guess it was bound to.

This blog is about “our parts.” It’s about that zone, from Bosnia to Bengal that, whatever its cultural complexity and variety, constitutes an undeniable unit for me. Now, I understand how the reader in Bihać, other than the resident Muslim fundamentalists, would be perplexed by someone asserting his connection to Bengal. I can also hear the offended screeching of the Neo-Greek in Athens, who, despite the experiences of the past few years, or the past two centuries, not only still feels he’s unproblematically a part of Europe, but still doesn’t understand why everyone else doesn’t see that he’s the gurgling fount of origin and center of Europe.

But set aside for one moment Freud’s “narcissism of petty differences,” if we have the generosity and strength to, and take this step by step. Granted there’s a dividing line running through the Balkans between the meze-and-rakia culture and the beer-and-sausage culture (hats off to S.B. for that one), but I think there’s no controversy in treating them as a unit for most purposes; outsiders certainly have and almost without exception negatively. And the Balkans, like it or not, include Greece. And Greece, even more inextricably, means Turkey, the two being, as they are, ‘veined with one another,’ to paraphrase the beautiful words of Patricia Storace. Heading south into the Levant and Egypt, we move into the Arab heartland that shares with us the same Greek, Roman-Byzantine, Ottoman experiences, and was always a part of the same cultural and commercial networks as the rest of us. East out of Anatolia or up out of Mesopotamia I challenge anyone to tell me where the exact dividing line between the Turkic and Iranian worlds are, from the Caucasus, clear across the Iranian Plateau into Afghanistan and Central Asia.

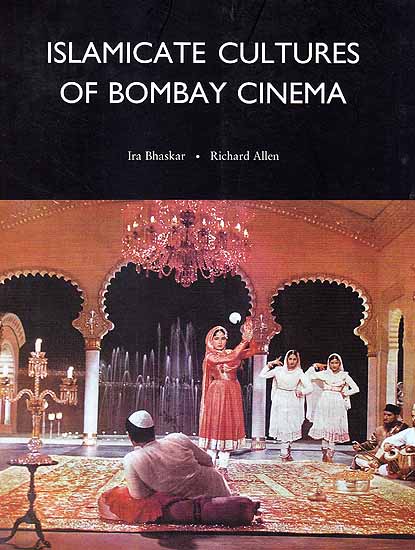

Granted, the descent into the suffocating Indo-Gangetic plain and its polytheism, from the suffocating monotheism of the highlands, is a cultural and most of all perhaps, a sensory rupture. But one has to know nothing about the “dazzlingly syncretic” civilization of north India to not know how much of it is Islamo-Persian in origin or was at least forged in an Islamic crucible, and if you do know that then the Khyber pass becomes what it always was, the Khyber link.

Are the borders of this zone kind of random? Maybe. But to step into Buddhist Burma is somehow truly a leap for me, which maybe I would take if I knew more. And in the other direction, I stop in Bosnia only because for the moment I’d like to leave Croatia to Europe – mit schlag – if only out of respect for the, er, vehemence with which it has always insisted that it belongs there. Yes, I guess this is Hodgson’s “Islamicate” world, since one unifying element is the experience of Islam in one form or another, but I think it’s most essential connections pre-date the advent of Islam. I’ll also probably be accused, among other things, of Huntingtonian border drawing, but I think those borders were always meant to be heuristic in function and not as hard-drawn as his critics used to accuse him of, and that’s the case here as well.

Ultimately what unites us more singularly than anything else, and more than any other one part of the world, is that the Western idea of the ethnic nation-state took a hold of our imaginations – or crushed them – when we all still lived in complex, multi-ethnic states. What binds us most tightly is the bloody stupidity of chilling words like Population Exchange, Partition, Ethnic Cleansing – the idea that political units cannot function till all their peoples are given a rigid identity first (a crucial reification process without which the operation can’t continue), then separated into little boxes like forks after Easter when you’ve had to use both sets – and the horrendous violence and destruction that idea caused, causes and may still do in “our parts” in the future.

What I hope this blog accomplishes, then, is to create even the tiniest amount of common consciousness among readers from the parts of the world in question. A very tall order, I understand, maybe even grandiose. Time will tell if it all ends up an unfocussed mess and I end up talking to myself; it’s very likely. But hopefully readers will respond and contribute material or comments even if they don’t feel the entire expanse of territory as their own. I hope it’ll be a place where one can learn something, including me; in fact, I expect most of my posts will end with “does anybody know anything more about…” or “can anyone explain…” I’ll be using vocabulary and making references from all over the place, sometimes footnoting them with an explanation, but if not hoping that readers will be interested enough to please, please ask when a word or topic is unfamiliar.

Clearly my intentions are more than just explicitly anti-nationalist, but please feel free to contribute even if you consider yourself ardently opposed to those intentions (just refrain from vulgarity please). Feel free to tell us how you’re the origins of civilization or how you saved it or how you restarted it or that you speak the first language that came from the Sun or that we don’t understand that you’re surrounded by enemies or that — in the language of a grammar school playground — you were here first and they started it, or how everything beautiful about your neighbors is ripped off from you and how everything ugly about you is the unfortunate result of your neighbor’s polluting influence. Feel free to express legitimate concerns and disagreements as well. Please.

I’m also sure that sooner than later the subject matter will spill over into neighboring areas (the rest of eastern Europe and southern Italy immediately come to mind), and that there’ll be occasional comments on American socio-political reality, which for better or worse affects us all. And there will probably be the more than occasional post on New York, because that’s where I live, that’s where I’m from, because it’s only from a vantage point that’s both heterogeneous and external that the phenomena I’ll be talking about can be apprehended in their fullness and because that’s where, more than any other single place or any single time in history, the cosmopolitan ideal that motivates me has manifested itself in one actual, throbbing, hopelessly chaotic and deeply sure of itself city.

I’ve been collecting material for this blog for a long time before actually sitting down to start it up, partly because life got in the way, as it tends to do, and partly cause I’m a technological spaz, so some stuff will be old (including some journal entries from a couple of years ago when I took a trip through the region), but my comments will be contemporary. If there’s any one out there in NYC who is inspired or interested enough to help me out with things like the blog’s design or things like Greek or Arabic fonts or Turkish letter markings (sorry, on a volunteer basis for now) please feel more than free to contact me at: nikobakos@gmail.com

Tags: Afghanistan, Albania, Balkans, Bengal, Bosnia, Byzantines, Ethnic Cleansing, Greece, Greeks, India, Iran, Nation-State, Nationalism, Nemerčka, Neo-Greek, New York, Partition, Patricia Storace, Population Exchange, Turkey