The Valley of Dropoli, the pass up to the Pogoni plateau near Libochovo, and in the distance, the snowcapped peaks of Nemerčka, from the Monastery of the Taxiarches in my father’s village of Derviçani, Easter 2014 (click)

The Valley of Dropoli, the pass up to the Pogoni plateau near Libochovo, and in the distance, the snowcapped peaks of Nemerčka, from the Monastery of the Taxiarches in my father’s village of Derviçani, Easter 2014 (click)

I’m honored by the fact that this really intelligent blog quotes extensively from the Jadde’s mission statement in a recent post: “Jadde — Starting off — the Mission.“

Check them out: The Classical Liberals: At least, most of the time Smart, perceptive, interesting stuff.

The author of the post below and the person I suspect is largely behind the editing of the blog is one Eoin Power, not just a fellow Balkan-freak along the lines of me or Rebecca West, but also a fellow Epirote. He demurs a bit — though not very convincingly — at being called an Epirote, because his lineage is multiple and complicated and the connection to Epiros is fairly distant historically. But he’s from one of the most archetypically and ancient Epirotiko villages — where they still own their patriko — in one of the most archetypically Epirotiko regions of Epiros and he carries himself with the requisite Epirotiko dignity and soft-spokeness and if I, NikoBakos, have conferred the title on you, it’s ’cause you deserve it.

***************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

On the Balkans, the Former Yugoslavia, and the Unity of Spaces

The other day, as she is wont to do, my mother sent me a link to something on the Internet; this time it was to Nicholas Bakos’ blog, which you can find here. If you’re reading this blog, we’re probably friends in real life (thanks for reading!), and so it’s probably obvious why something like that would be of interest to the both of us. I have admittedly only skimmed sections of his posting so far, but in his introductory one, it was especially gratifying to read this:

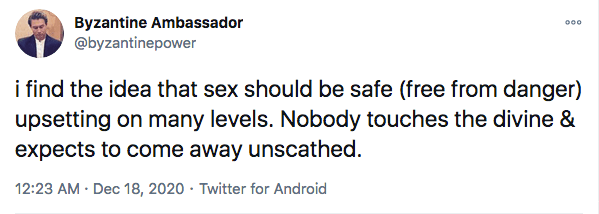

This blog is about “our parts.” It’s about that zone, from Bosnia to Bengal that, whatever its cultural complexity and variety, constitutes an undeniable unit for me. Now, I understand how the reader in Bihać, other than the resident Muslim fundamentalists, would be perplexed by someone asserting his connection to Bengal. I can also hear the offended screeching of the Neo-Greek in Athens, who, despite the experiences of the past few years, or the past two centuries, not only still feels he’s unproblematically a part of Europe, but still doesn’t understand why everyone else doesn’t see that he’s the gurgling fount of origin and center of Europe.

But set aside for one moment Freud’s “narcissism of petty differences,” if we have the generosity and strength to, and take this step by step. Granted there’s a dividing line running through the Balkans between the meze-and-rakia culture and the beer-and-sausage culture (hats off to S.B. for that one), but I think there’s no controversy in treating them as a unit for most purposes; outsiders certainly have and almost without exception negatively. And the Balkans, like it or not, include Greece. And Greece, even more inextricably, means Turkey, the two being, as they are, ‘veined with one another,’ to paraphrase the beautiful words of Patricia Storace. Heading south into the Levant and Egypt, we move into the Arab heartland that shares with us the same Greek, Roman-Byzantine, Ottoman experiences, and was always a part of the same cultural and commercial networks as the rest of us. East out of Anatolia or up out of Mesopotamia I challenge anyone to tell me where the exact dividing line between the Turkic and Iranian worlds are, from the Caucasus, clear across the Iranian Plateau into Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Bakos suggests that for people of “those parts” displaced to another environment (e.g. grad school in the West), this kind of geographical unity came, at least in a social context, fairly naturally, so perhaps I shouldn’t be all that surprised and delighted at seeing it reconstituted in blog form. But in fact I think the basic unity of the geographical zone outlined here often gets lost in the way these places are understood by outsiders and, ironically enough, in no small part due to the vehement insistence from each of the zone’s component peoples that they could not possibly be compared with those uncultured idiots with whom they share a border.*

Explaining the rationale for delineating “his parts” the way he does, Bakos writes:

But to step into Buddhist Burma is somehow truly a leap for me, which maybe I would take if I knew more. And in the other direction, I stop in Bosnia only because for the moment I’d like to leave Croatia to Europe – mit schlag – if only out of respect for the, er, vehemence with which it has always insisted that it belongs there. Yes, I guess this is Hodgson’s “Islamicate” world, since one unifying element is the experience of Islam in one form or another, but I think it’s most essential connections pre-date the advent of Islam. I’ll also probably be accused, among other things, of Huntingtonian border drawing, but I think those borders were always meant to be heuristic in function and not as hard-drawn as his critics used to accuse him of, and that’s the case here as well.

Ultimately what unites us more singularly than anything else, and more than any other one part of the world, is that the Western idea of the ethnic nation-state took a hold of our imaginations – or crushed them – when we all still lived in complex, multi-ethnic states. What binds us most tightly is the bloody stupidity of chilling words like Population Exchange, Partition, Ethnic Cleansing – the idea that political units cannot function till all their peoples are given a rigid identity first (a crucial reification process without which the operation can’t continue), then separated into little boxes like forks after Easter when you’ve had to use both sets – and the horrendous violence and destruction that idea caused, causes and may still do in “our parts” in the future.

Having not, at least north of the equator, yet made it further east than Istanbul, I am in no position to question Bakos’ perception of the fundamental apartness of Buddhist Burma. But the loose border he posits to the north and west is one I’ve crossed many times, and it’s one that is both deeply present and functionally invisible.**

At the very least it is present in people’s minds; I can vouch for the vehemence (to use Bakos’ word again) with which Slovenes and Croats will insist that their countries are European, and not Balkan. It’s also pretty visually observable – you could mistake Zagreb or Ljubljana for a city in Austria or Germany in a way you simply can’t for, say, Sarajevo or Belgrade. And on one frantic trip from Dubrovnik back to Ljubljana (the ferry which I’d intended to take from Dubrovnik to Ancona decided not to arrive from Split, leaving me nothing to do but beat a hasty retreat back north) you could, if you were looking for it, see an actual tangible difference in the way things were done in the world – bus tickets in Mostar and train tickets in Sarajevo had to be paid in cash and a conductor on the train north from Sarajevo let me pay in a mix of Croatian kuna, Bosnian marks, and euros. In Zagreb I could pay with a credit card, the train station had working and appealing amenities, and you couldn’t smoke in the train. This is a terribly squishy thing to write, but it did feel more “European-y”.

On the other hand, if the relatively old Huntingtonian dividing line between formerly Orthodox and Ottoman lands to the south, and formerly Catholic Hapsburg lands to the north is visually (and, at least in terms of credit card viability in 2009, functionally) discernible, the comparatively recent unifying experience of Yugoslavia is also unavoidable. Here, too, the first signs are in architecture and appearance; Soviet-style architecture and the legacy of 1950s industrialization has left the same physical scars on cities from Nova Gorica to Skopje. But they run deeper than that – the protestations of linguistic nationalists notwithstanding, Slovene, Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Montenegrin, Macedonian (hell, even Bulgarian a bit) all exist along a spectrum of of mutual intelligibility; state apparatuses, all having those of the former Yugoslavia as their common predecessors, share similar characteristics. Indeed, to me as a foreigner, the similarities often seem more salient than the differences.

Just on the basis of whether or not there “is” a usefully differentiating border to be drawn where Croatia meets Bosnia, it seems you can argue fairly fruitfully either way, depending on whether your sympathies lie with a sort of longue duree emphasis on deep civilizational splits or a faith in the primacy of modern political experiences. But by Bakos’ own ultimate criteria, it seems a bit odd to leave the northernmost bits of the former Yugoslavia out of things (though there is a nice alliterative symmetry to covering “from Bosnia to Bengal”) . If you’re going on the basis of, “the bloody stupidity of chilling words like Population Exchange, Partition, Ethnic Cleansing,” surely things like Jasenovac or the Istrian exodus argue for the inclusion of all of the former Yugoslavia?

Of course, any exercise in boundary-izing is a bit arbitrary, and in this case there are good reasons to put one in between Croatia and Bosnia and not, say, in between Slovenia and Austria (two countries for which there also exist plenty of historical reasons to consider them as part of a unified space). So if all of this does anything, it is perhaps to show how much more liminal are most places than we or their inhabitants often care to admit; whether or not you see a border somewhere often depends as much on your level of zoom as anything else.

*Or at least their nationalist politicians – many average people (whatever that means) in Bosnia and Serbia, for example, will quickly stress to you the fundamental similarities between the two countries and their inhabitants

**People sometimes marvel at my overstuffed passport but really something like 40% of the stamps come from the Dobova and Dobrljin border posts.

**************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Again, check these guys out; you won’t regret it: The Classical Liberals

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

Tags: "The Classical Liberals", Anatolia, Arabs, Austria, “narcissism of petty differences”, Balkans, Bengal, Bihać, Bosnia, Constantinople, Croatia, Croats, Dobova, Dobrljin, Dropoli, Dubrovnik (Ragusa)., Eoin Power, Epiros, Epirote, Ethnic Cleansing, Freud, Germany, Greece, Greeks, Huntington, Iranians, Islam, Istanbul, Libochovo, Ljubljana, Mesopotamia, Montenegrins, Nemerčka, Orthodox Christianity, Ottoman Empire, Partition, Pogoni, Population Exchange, Rebecca West, Romans, Slovenes, Turkey, Turks, Yugoslavia, Zagreb

Ein Zebde peach orchards

Ein Zebde peach orchards