This goes out to my best friend in the world. We’re different — maybe it’s the complementarity that has sustained the friendship since I was eighteen — and we like to rag on each other a lot. I call him a technocrat who can’t understand anything unless it can be put on a spreadsheet; he calls me a poetry-addled flake from another planet; both contain a large dose of truth. At the same time he has the largest heart and the most profoundly musical soul of any person I have ever met. He remembers how when he first heard this song at eight years old, he fell into a crying fit that kept him awake all night; it wasn’t the lyrics, it was the melody that “turned him into rags” as we say in Greek, “my mother at my bedside asking me ‘what’s wrong, my son?,’ me sobbing uncontrollably…”

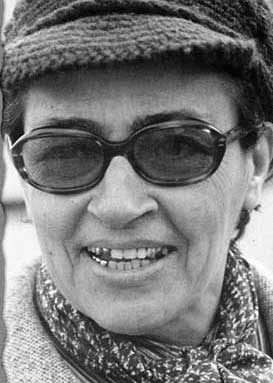

I can’t post the original 1947 video he sent me because some copyright b.s. makes it unviewable in the U.S., so I found a beautiful rendition (along with odd but interesting video) by the great Swteria Mpellou, one of the great cultural icons of modern Greece; read about her fascinating, heroic life; like with many flamenco or blues singers, it wasn’t the classical beauty or timbre of her voice that made her great; it was her voice’s indefinable character, its soul.

The lyrics:

Ξύπνα, μικρό μου, κι άκουσε

κάποιο μινόρε της αυγής,

για σένανε είναι γραμμένο

από το κλάμα κάποιας ψυχής.

Το παραθύρι σου άνοιξε

ρίξε μου μια γλυκιά ματιά

Κι ας σβήσω πια τότε, μικρό μου,

μπροστά στο σπίτι σου σε μια γωνιά.

Wake up my little one,

and hear a dawn minore,

written for you by the weeping

of some soul.

Open your window

and throw me just one sweet glance,

and then let me be extinguished, my little one

in some corner, outside your house.

Swteria Mpellou

“A Dawn Minore” is a rebetiko — though a late-style, more commercial example of that genre — music which has its origins among the Greek proletariat of Anatolian cities — more so Smyrna than Constantinople (I imagine that in C-town the classical tradition was too strong and the other alternatives were more a la Franca, though whatever more popular genres contemporary “arabesque” comes from must have been present). It took its definitive form, however, among the largely refugee proletariat of Athens, Piraeus, and Salonica, after the Population Exchange of the 1920’s. Because of its association with Turkey, the poor, crime, drugs, the underworld, but mostly because its “orientalness” didn’t sit well with the Westernizing agenda of the Neo-Greek bourgeoisie, it was subject to much discrimination, marginalization and even official bans of varying efficacy. Eventually, however, and with the recognition of geniuses like Hatzidakis, it became the basis of modern Greek music, especially that of its Golden Age between the fifties and the seventies, when Greece produced popular music that, for the quality of its compositions and high poetic standard of its lyrics, may be unmatched in any modern commercial genre, and which, along with Cavafy, I consider the great cultural achievement of twentieth-century Greek culture. Under unknown circumstances, this musical florescence suddenly expired in the early eighties at some point (Pasok and its lethal, lefty didacticism?). A craze for old rebetika (pl.) which suddenly exploded in Greece at the same time, probably represented a need to fill the gap: nostalgia is usually a symptom of creative sterility.

Irony: Tsitsanes, lionized as the greatest rebetiko composer and bouzouki player, but who I never thought was all that, published a series of virulent, racist rants against the Hindi-film influenced genre of popular music that developed in Greece in the fifties, decrying its “corrupt, oriental cheapness,” that could have been written, with the same vocabulary, by a Greek bourgeois ranting against rebetiko itself two decades earlier.

Irony: Many of the young Neo-Greeks that have fetishized rebetiko since the eighties (the little Athenian snots who will only listen to authentic rebetiko first renditons off of 78’s — that, or Miles) till the point where the aural environment of Greece became so saturated with it that it could drive you nuts, will also still express the same Orientalist, petit bourgeois anti-“easterness” towards other music that previous generations did toward rebetiko. “I can’t tolerate any form of Eastern music” a thirty-something Athenian recently told me (with the crucial condescending stress difference between “anato-li-tike” and “anatoli-ke) which for the sociological type in question almost always means any microtonal, highly chromatic music, which, freed from polyphony — except for the simple drones of Hindustani classical music or of certain Balkan folk music — and the structural complexities of Western harmonies, can throw all its craft into the highly embroidered monophonic melodic line — which essentially means all music from Greece eastwards. This was announced to me with great disgust while I was listening to a sublime Shajarian rendition of a Fereydoon Moshiri poem, disparaged as “amanedes”* (if she only knew the caliber of artists she was talking about…) “Eastern music?” I replied. “So, you mean our entire musical tradition before “Barba Yianne me tis Stamnes?”** She didn’t have an answer to that.

Heresy: Most rebetika contain neither the intriguing depth of Western harmony nor the possessing melodic intricacy of Arab or Persian classical music, or even Greek ecclesiastic music, which is why I often find them a bit tedious and am not part of the general fan club, and I consider its popular offspring of later decades (the Golden Age, a masterful combination of rebetiko, various folk genres, western forms and the best poetry of the period — prepare for a “Golden Age” series of posts) to be the by far superior music on every level.

Positive: Rebetiko, in a strangely poetic voyage back across the Aegean, became wildly popular in Turkey in the nineties, with Turks forming their own groups and everything (I’ll find an example) and has since become a happy space where much musical collaboration and explicit mutual affection is expressed.

Final YouTube comment from a Greek on another video: “Πέθανε αυτή η Ελλάδα. Ας το καταλάβουμε μπας και γλυτώσουμε από τα ΑΚΟΜΑ χειρότερα…” “That Greece is dead. If we get it through our heads maybe we’ll be spared EVEN worse.”

*”Amanedes” are a light classical Turco-Greek genre that flourished in early twentieth-century Smyrna. I don’t think it ever called itself that; the mostly negative term comes from the frequent repetition of “aman,” mercy in Turkish, in its lyrics. It’s mostly disparaging, like when used by the person above, to deprecate some kind of music as “Turkish” “Eastern” “oriental wailing” etc…

**”Barba Yianne me tis Stamnes” is an exemplary piece of an extremely silly barber-shop quartet genre that became popular in early twentieth-century Greece, based on the Italianate “cantada” tradition of the Ionian islands, which is like bad Neapolitan music without the passion, wit, complexity or subversiveness. I can’t find a recording of it. The thought that if it hadn’t been for the refugee influx of the twenties, that could have become the future of Greek music sends chills down my spine. (Here you go– from a Turkish website — go figure.)

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com