The idea that Afghans are “economic migrants”…

…unlike Syrians and Iraqis, because Afghanistan is no longer a war zone, is obscene. What does the barometer for endemic violence, chronic poverty or a people’s desperation have to read for someone to be considered a “real” refugee?

**************************************************************************************

And some more recent articles on recent developments:

Europe Is Called ‘Willfully Blind’ to Risks Afghan Deportees Face

(“scathing” Amnesty report from last year)

Afghans who were deported from Germany to Afghanistan at Kabul International Airport in December. The United Nations says Europe is ignoring the dangers of their return to the strife-torn country.CreditMassoud Hossaini/Associated Press

Afghans who were deported from Germany to Afghanistan at Kabul International Airport in December. The United Nations says Europe is ignoring the dangers of their return to the strife-torn country.CreditMassoud Hossaini/Associated Press

And today or yesterday I think:

Their Road to Turkey Was Long and Grueling, but the Short Flight Home Was Crueler

About 60 Afghan men were being deported aboard a flight to Kabul from Istanbul last month, including Abdul Mohammed, right. They had spent months on a dangerous journey to Turkey, only to be returned home on a five-hour flight.CreditMujib Mashal/The New York Times

About 60 Afghan men were being deported aboard a flight to Kabul from Istanbul last month, including Abdul Mohammed, right. They had spent months on a dangerous journey to Turkey, only to be returned home on a five-hour flight.CreditMujib Mashal/The New York Times

I can’t say anything. Because this is really an “απορώ και εξίσταμαι” moment for me. It’s too shameful; it’s too cruel (cruelty compounded by Western blackmail); it’s too CHEAP and horrendously VULGAR. It’s just inconceivable. Read them.

And, of course, trigger-happy Iranian border guards are mentioned x number of times, while there’s only the mildest whiff of criticism of Turkey ethically and morally.

“They [the deportees] see it more simply: They tried, they were caught, they will try again.”

As I’ve said so often before, I can’t figure out where Afghans get their strength from. Something like Primo Levi’s insisting on your own humanity? At the end times or just when their martyrdom is over, Afghans will inherit the earth.

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

**********************************************************************************

More. See Washington Post article for photos

A ship full of refugees fleeing the Nazis once begged the U.S. for entry. They were turned back

Nine hundred thirty-seven.

That was the number of passengers aboard the SS St. Louis, a German ocean liner that set off from Hamburg on May 13, 1939. Almost all of those sailing were Jewish people, desperate to escape the Third Reich. The destination was Havana, more than two weeks away by ship.

So begins a haunting tale, one that would end tragically for hundreds of those on board — so much so that, decades later, it would be the basis for the movie “Voyage of the Damned.”

Before the St. Louis even left Hamburg, there were indications the passengers might have problems disembarking in Cuba. The ship’s owners knew many travelers were likely holding invalidated landing certificates, according to research by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Thousands of miles away, anti-Semitic protests and editorials were cropping up all over Cuba.

“Many Cubans resented the relatively large number of refugees (including 2,500 Jews), whom the government had already admitted into the country, because they appeared to be competitors for scarce jobs,” the museum noted. “Hostility toward immigrants fueled both antisemitism and xenophobia. Both agents of Nazi Germany and indigenous right-wing movements hyped the immigrant issue in their publications and demonstrations, claiming that incoming Jews were Communists.”

[‘The Holocaust did not begin with killing; it began with words.’ Museum condemns alt-right meeting.]

Still, the inhospitable circumstances awaiting them paled in comparison to what the passengers wanted to flee in Europe, and so the ship set sail. When the St. Louis arrived in Havana two weeks later, only 29 passengers were allowed into the country. The other 907 were ordered to remain on the ship. (One person had died en route of natural causes.)

As futile negotiations with the Cuban government ensued, the would-be asylum-seekers redirected their pleas to the American government. They would be in vain.

“Sailing so close to Florida that they could see the lights of Miami, some passengers on the St. Louis cabled President Franklin D. Roosevelt asking for refuge,” the Holocaust museum noted. “Roosevelt never responded.”

A State Department telegram stated, simply, that passengers must “await their turns on the waiting list and qualify for and obtain immigration visas before they may be admissible into the United States.”

Finally, the St. Louis returned to Europe. After more than a month at sea, the passengers disembarked in Antwerp, Belgium, where they were divided between four countries that had agreed to take them: Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium and France.

By the end of the Holocaust, 254 of them would be dead.

[Trump order barring refugees, migrants from Muslim countries triggers chaos, outrage]

Nearly eight decades after its doomed voyage, some drew parallels between the U.S. government’s dismissal of the St. Louis and the possible consequences of President Trump’s executive order temporarily banning immigration.

Trump on Friday signed orders not only to suspend admission of all refugees into the United States for 120 days but also to implement “new vetting measures” to screen out “radical Islamic terrorists.” Refugee entry from Syria, however, is suspended indefinitely, and all travel from Syria and six other nations — Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen — are suspended for 90 days. Trump also said he would give priority to Christian refugees over those of other religions.

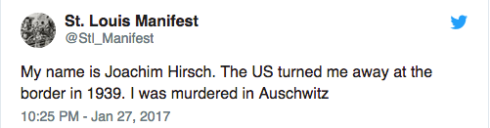

Earlier that same day, one by one, testimonials from the passengers that had been aboard the St. Louis — and who afterward died at the hands of the Nazis — began appearing on the Twitter account “St. Louis Manifest” (@Stl_Manifest).

Periodically, a cluster of tweets would indicate family members who had perished together.

My name is Arthur Weinstock. The US turned me away at the border in 1939. I was murdered in Sobibor …

My name is Charlotte Weinstock. The US turned me away at the border in 1939. I was murdered in Sobibor …

My name is Ernst Weinstock. The US turned me away at the border in 1939. I was murdered in Sobibor …

The “St. Louis Manifest” Twitter account, which gained more than 52,000 followers within two days, was the product of Russel Neiss, a Jewish activist and educator who used data from the Holocaust museum to build the bot.

Neiss said he collaborated with Rabbi Charlie Schwartz on the project in part to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Friday — but also “with an eye to our current political climate.”

“People always say that if you forget history then you will be doomed to repeat it,” Neiss told the Atlantic. “This is one of those moments where history gives us an opportunity to think about where we are now. When folks say ‘never again’ or ‘we remember,’ it is important for us to actually do so.”

(Neiss minced his words less on social media. “Anyone who says #WeRemember or #NeverAgain while sitting silently while the US closes its doors is full of s—,” he tweeted Thursday.)

The Holocaust museum spent two years trying to track down every man, woman and child aboard the St. Louis and find out what their fate was, according to a 1999 article in The Washington Post. That year, the museum opened an exhibition about the voyage that “makes you work hard, and leaves you feeling sick at heart,” reporter Michael O’Sullivan wrote in his review of the gallery.

The display included pictures of the St. Louis passengers, newspaper articles of the ship’s ordeal and “gut-churning letters that lay out disappointment after crushing disappointment,” he added.

[What Americans thought of Jewish refugees on the eve of World War II]

“Even more, the drama of dashed hopes and national shame that plays out on these few walls is itself an uneasy one, for in a half-dozen glass cases we can see reflected a bony finger of blame pointed squarely back at us,” O’Sullivan wrote.

Photographs, personal histories, artifacts and maps relating to the St. Louis are available online through the Holocaust museum’s website.

The voyage of the St. Louis is just one example in history of “what happened when people slam doors shut on refugees,” said James C. Hathaway, a law professor at the University of Michigan and director of its program in refugee and asylum law.

Reached by phone Saturday, Hathaway said it was easy to draw comparisons between the fate of those aboard the St. Louis and, fewer than three generations later, the indefinite suspension of refugees from Syria.

The current situation in Syria is “probably the easiest example in the world today of people being massacred by a political tyrant,” Hathaway said. “That we would not read the tea leaves of history and understand that the people fleeing are the enemies of our enemy is beyond comprehension to me.”

Kristine Guerra contributed to this article.

Read more:

‘I am heartbroken’: Malala criticizes Trump for ‘closing the door on children’ fleeing violence

Anne Frank and her family were also denied entry as refugees to the U.S.

Leave a comment