Instead, he bummed around Indiana, doing odd jobs. His stepfather had him wheel their lawnmower around to neighbors’ houses and offer to mow their lawns, which he found humiliating. He made telemarketing calls for a basement-waterproofing company. He sold Kirby vacuums, or tried to—he doesn’t remember selling a single vacuum. At one point, he was driving around Chicago in the three-piece suit he wore for church, hawking stress balls and National Geographic videos about whales. “I was basically peddling shit,” he said. He convinced himself that he could use his acting skills to entice people. During one telemarketing call, he asked a woman if her husband was home. “There was a long pause, and she says, ‘My husband’s dead!’ and started crying and hung up the phone. I felt terrible.”

Joining the Marines gave Driver a sense of purpose and some distance from his conservative religious upbringing. “The nice way of saying it is, it’s not part of my life anymore,” he said of the church, though he emphasized that he considers faith and religion to be two separate things. He is wary of discussing his parents or religion. In 2014, his stepfather told the South Bend Tribune, “I don’t agree with everything that he does, but I agree with his work ethic.” His mother didn’t know that he was on “Girls” until the second season, when she found out from a co-worker.

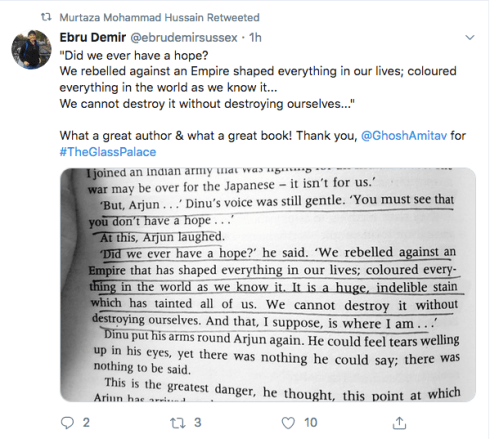

The pull between faith and apostasy has interlaced his movie roles. In “Silence,” he based his character, Father Garupe, on St. Peter. “He’s the only one that’s questioning, and I find that is healthier,” Driver said. “Doubt is part of being committed to something, I think. They’re very hand in hand, and that seemed more human to me. Garupe, in that story, he’s committed, and then at a certain point he’s, like, ‘This is fucking bullshit.’ I feel that with religion. I feel that with acting. I feel that with marriage. I feel that with being a parent. I’m constantly filled with doubt, regardless of what I’ve accomplished. It doesn’t mean anything. You still don’t know how to do anything, really.” He described Kylo Ren, in “Star Wars,” as “the son of these two religious zealots”—meaning Han Solo and Leia—who “can be conceived as being committed to this religion above all else, above family.” Part of him still feels blindsided, as if he’d missed a class and hadn’t yet caught up on the wider world. While discussing “Fight Club,” he asked what I thought of the movie. I said that I hadn’t seen it in years but wondered how it would play in an era when people are hyperaware of toxic masculinity.

“What do you mean, ‘toxic masculinity’?” he asked.

I suggested that male aggression is seen as less purifying now than it may have been portrayed as being in “Fight Club.” “I’d have to think about it,” Driver said. “I mean, I haven’t heard much about toxic masculinity.” He chuckled. “Maybe because I’m part of the problem!”

Hours later, in his dressing room, he was talking about how his suspicion of dogma shaped him as an actor. “For a lot of times in my life, I was told there was a right answer,” he said. “And then, when I got older, I was, like, ‘That’s fucking total bullshit.’ I feel that very much with acting, too. If you knew how to do it, you would do it perfectly every time.” He added, “So anytime anyone tells me, ‘This is the right answer,’ or ‘There’s something called toxic masculinity,’ I’m, like, What? What are you talking about? I’m skeptical of it, because I feel like I was duped for seventeen years of my life.”

In early October, Driver was at Lincoln Center, where “Marriage Story” was the centerpiece of the New York Film Festival. He had flown in from Brussels, where he was filming “Annette,” with the French director Leos Carax, and landed at 3:30 a.m. That evening, there was a red-carpet première, and at midnight he would fly to England, for the London Film Festival.

Baumbach said that when he was writing “Marriage Story” he had long phone conversations with Driver in which they discussed such classic movies as “The Red Shoes” and “To Be or Not to Be.” One of their abandoned ideas, a film version of Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Company,” found its way into the script in the form of two musical numbers. (Baumbach told me that Driver had recently sent him a photograph of the Mets pitcher Noah Syndergaard, who has a blond, Thor-like mane, with the message “This would be good for something.”)

At noon, Driver was clutching a cup of coffee in a greenroom at the Walter Reade Theatre, before a press conference. The cast trickled in: Laura Dern, Alan Alda, Ray Liotta. (Johansson was stuck in traffic.) Liotta, who plays a divorce lawyer, approached Driver. “Hey!” he said in greeting, then struck a reverent tone. “Did you serve?”

“Yes,” Driver said shyly, standing to shake his hand.

“Wow,” Liotta said. “Thank you for your service. Seriously. My trainer was a marine.”

Driver quickly changed the subject. His military background makes him anomalous in Hollywood; the days of Clark Gable and Jimmy Stewart leaving pictures to fly combat missions are long gone. Though his time in the Marine Corps was formative—and gave rise to a nonprofit organization he founded, Arts in the Armed Forces, which fosters art appreciation among the troops—it came to a disappointing end. After more than two years of training, Driver was preparing to ship out to Iraq. At the time, he wasn’t thinking about the politics of the Iraq War, he said, just about his loyalty to his guys. One morning, he and his friend Garcia went mountain biking in Pendleton’s Camp Horno. On the way down, Driver hit a ditch. The handlebars slammed into his chest, and he dislocated his sternum.

Driver’s first sergeant told him that he was too injured for the deployment. Attempting to prove otherwise, he loaded up on hydrocodone and worked out in the gym, but he made the damage worse. He was honorably discharged, while his former platoon shipped out to the southeast tip of Iraq, to run security missions on the Iranian border. It was early in the war, and the unit returned safely. But Driver was devastated. “They had gone and done the thing that we trained to do together,” he said. “And I felt like a piece of shit.”

Driver’s platoon commander, Ed Hinman, had always found him more “pensive” than the others. “There was something more going on, I could tell, between his ears,” he told me. Hinman said that life after the Marines can be tough under any circumstances. “You go from being in a family to being on your own, without an identity and without a mission. And, if you know it’s coming, that’s one thing. But if you don’t, like Adam, that can be pretty scary.”

Humiliated, Driver drove back to Indiana in a Ford F-150 he’d bought from an officer and enrolled at the University of Indianapolis, where he acted in Beckett’s “Endgame” and in the musical “Pippin.” He applied to be a policeman but was turned down, because he was under twenty-one—“Which was ironic to me, because I was a SAW gunner, and suddenly I can’t handle a Glock?”—so he got a job as a security guard. But he felt adrift, his mission unfulfilled. Then, remembering his brush-with-death vow to be a professional actor, he went back to Chicago and re-auditioned for Juilliard.

Richard Feldman, a Juilliard teacher, recalled, “This very interesting young man walked in the room—big, tall, lanky, with hair partially flopping over his face.” Driver performed the opening lines from “Richard III,” a contemporary monologue he’d found at a Barnes & Noble, and, for his musical selection, “Happy Birthday to You.” His acting wasn’t polished, but, to Feldman, he radiated something genuine. Driver was guarding a Target distribution warehouse when he got the call that he’d been accepted. “I ran up and down the truck area, jumping around,” he said. “I was fucking elated.”

In the summer of 2005, he moved into a closet at an uncle’s house, in Hoboken. He got a job at Aix, a French restaurant on the Upper West Side, where he served asparagus to Tony Kushner. He was as good at waiting tables as he was at selling vacuums. “I’d never heard of broccoli rabe,” he said ruefully. Juilliard was a shock. He’d gone from firing mortars to pretending to be a penguin in improv exercises. He was disdainful of civilian life, sneering at classmates who wore their shirts untucked or arrived late to class. One time, he snapped so sharply at a student who had used his yoga mat that he reduced the guy to tears. “I was, like, I gotta be better at communicating,” he said. He holed up at the performing-arts library and read plays by David Mamet and John Patrick Shanley, and found that drama helped him express his roiling emotions.

His classmates were mystified by the hulking ex-marine. Gabriel Ebert, who later won a Tony Award for his role in “Matilda the Musical,” recalled their 9 a.m. movement classes: “I probably got there at eight-forty-five to stretch, and Adam was already in a full sweat, like he’d been there for at least an hour working out. He brought a discipline to his physical prowess that most of us didn’t learn until well into our second year.” Driver and Ebert got an apartment in Queens, and Driver would run five miles to school every day. He did pushups by the hundreds in the hallways and ate six eggs for breakfast (minus four of the yolks) and an entire chicken, from Balducci’s, for lunch.

Driver met Joanne Tucker, a classmate, during his first year. “She read a lot of books, knew a lot of shit,” he said. “She was very composed.” Her family lived in Waterside Plaza, in Murray Hill, and Driver would go over and eat all their cereal. Feldman, who, in 2013, officiated at their wedding, told me that Tucker didn’t stand for Driver’s holier-than-thou attitude: “She doesn’t take any nonsense.”

Acting wasn’t entirely different from military life: both required a team effort and a sense of mission. But when Driver saw his marine buddies he would poke fun at his cushy new life, ashamed that he hadn’t joined them overseas. In his third year, he and Tucker started Arts in the Armed Forces. At Camp Pendleton, the “mandatory fun” had included a skateboarding show and a trivia game in which you could win a date with a cheerleader. (The “date” was a stroll around the parade deck.) “Even at the time, I was, like, This is nice, but it’s playing to the lowest common denominator,” Driver said. He wanted to bring the troops something smarter, and show them that theatre didn’t necessarily mean men in tights. Feldman told me, “Adam was always trying to unite these two aspects of his life that seem to us in contemporary America so contradictory: how can you be a soldier—a marine, of all things—and an artist?”

Driver appealed to the U.S.O., but was told that the military demographic wouldn’t be interested in plays, so he went to Juilliard’s president for funding and solicited alumni to participate. In January, 2008, he returned to Camp Pendleton for AITAF’s inaugural show, along with Ebert, Juilliard graduates including Laura Linney, and Jon Batiste, a jazz student from the music division (he is now the bandleader for “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert”). Ebert recalled, “Jon and I stood in front of a grocery store at Camp Pendleton and handed out flyers for hours. ‘Hey, you want to see some monologues? You want to see some jazz?’ ” Around a hundred people showed up—the competition was the college-football championship—and watched monologues by Danny Hoch and Lanford Wilson, under a marquee that read “Juilliard Performance: Adults Only.”

During his third year, Driver was cast in a play at the Humana Festival, in Louisville, Kentucky. Juilliard has a policy against students taking professional roles before graduation, so he would have to drop out. Feldman urged him to stay. “I asked him to think about whether he had ever had the chance to finish anything in his life,” Feldman recalled. “He’d left college. He had to leave the Marines, because he got injured. And I challenged him to finish this.” Driver went through every step of quitting except for turning in his keys—and then changed his mind. His fourth year, he performed “Burn This” with Tucker and got an agent. He graduated in 2009.

Driver had thought about becoming a firefighter if acting didn’t pan out, but his career took off almost immediately. In 2010, he appeared in a Broadway revival of Shaw’s “Mrs. Warren’s Profession,” with Cherry Jones, and in the HBO movie “You Don’t Know Jack,” starring Al Pacino as Dr. Kevorkian. The next year, he played a gas-station attendant in “J. Edgar,” directed by Clint Eastwood, and Frank Langella’s son in the Broadway play “Man and Boy.” He and Langella became close. “He’d come up to my country place on his motorcycle, play badminton, help move furniture, do the dishes,” Langella recalled. “Once, at my New York place, I gave him some old suits of mine, and he left, bunching them in his arms, heading for the subway. ‘Take a taxi,’ I said. ‘Nope,’ he said. ‘Too expensive.’ ”

Driver initially turned down the audition for “Girls,” on account of television being evil (“I was an élitist prick,” he says), but his agent persuaded him. The casting call described Adam Sackler as “a carpenter, incredibly handsome, but slightly off.” Driver showed up with a motorcycle helmet under his arm. Jenni Konner, Dunham’s co-showrunner, recalled the reaction in the room as ecstatic. “Remember the old Beatles films, where the women are screaming?” she told me. “That’s what his audition felt like.” As the show evolved, details of Driver’s life would seep into the scripts; in the third season, the fictional Adam lands a role in Shaw’s “Major Barbara” on Broadway, a nod to Driver’s appearance in “Mrs. Warren’s Profession.” “He was always someone I saw as a rhinoceros, who picked one thing and ran toward it,” Driver said of his character on “Girls.” “He can’t see left or right at all, just sees what’s immediately in front of him, and he chases it until he’s exhausted.”

The first time Driver saw himself in “Girls,” on Dunham’s laptop, he was mortified. “That’s when I was, like, I can’t watch myself in things. I certainly can’t watch this if we’re going to continue doing it,” he said. Many actors decline to watch themselves, but for Driver that reluctance amounts to a phobia. In 2013, he watched the Coen brothers’ “Inside Llewyn Davis,” in which he has one scene, singing backup on a folk song called “Please Mr. Kennedy”: “I hated what I did.” He swore off his own movies, until he was obliged to sit through the première of “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” in 2015. “I just went totally cold,” he recalled, “because I knew the scene was coming up where I had to kill Han Solo, and people were, like, hyperventilating when the title came up, and I felt like I had to puke.”

The directors I spoke to sympathized with Driver’s aversion. “I think he’s rightly concerned that he would become conscious of himself in a way that would be harmful to his acting,” Soderbergh said. When I spoke to Baumbach, he was still “in a discussion” with Driver about watching “Marriage Story.” Spike Lee told me that Driver did see “BlacKkKlansman,” at Cannes (“It was very, very happy”), but Driver corrected the record: he had hidden out in a greenroom and returned for the closing bow.

In September, I met Driver in Brussels, where he was shooting “Annette” on a soundstage. He plays a failing comedian; his wife, played by Marion Cotillard, is an opera singer on the rise. To ease the resulting tension, they take a sailing holiday with their baby, Annette, and get caught in a storm. That day’s scenes took place during the squall. In one corner of the studio, half of a life-size sailboat was mounted ten feet high on a gimbal, a mechanism that would toss and turn the boat like a mechanical bull, while a cyclorama projected a tempestuous curved backdrop around it. Sprinklers would unleash rain and fog, while water cannons spewed waves. Also, the film is a musical, so there would be singing.

Carax, the director, smoked a cigarette in his sunglasses, as Driver and Cotillard emerged from a pair of black makeup tents. They rehearsed the scene in which Driver draws Cotillard into a drunken waltz on the sailboat’s deck. He mocks her theatrics (“Bowing, bowing, bowing”), and she pleads with him in song (“We’re gonna fall, gonna die”), before he flings her offscreen. The film’s co-writers, Ron and Russell Mael, known from the seventies band Sparks, watched on a monitor. “We spoke very briefly to Adam about three years ago, just about the style of his singing,” Ron whispered to me. “We didn’t want it to be Broadway, you know?”

Driver, wearing a fake mustache, measured the exact distance to spin before accelerating in the final moment. “If I’m throwing her, I don’t want to wing it,” he said. There was little leeway for benign rebellion. Driver later told me, of Carax, “His movies to me feel very much like freedom—like captured chaos—but they’re very, like, ‘Turn here, move left here.’ So it’s like doing math, but then not making it look like we’re executing choreography.”

A crew member yelled, “Silence, s’il vous plaît,” and in came rain, thunder, lightning, and waves. Between takes, Cotillard sang her lines to herself, while Driver stretched his legs on the railing of the boat, like a dancer at a barre. During one take, they slipped and fell. “Are you O.K.?” Driver said, helping her up, then asked the gimbal operators if the device was turned on too high: “We did this all yesterday, and we didn’t slip once.”

Like Robert De Niro in his “Raging Bull” days, Driver is known for embracing physical feats. For “Silence,” in which Garupe is captured by the Japanese, he lost fifty-one pounds, on a diet of chocolate-flavored energy goo, sparkling water, and chewing gum. For “Paterson,” he learned how to drive a bus. For “Logan Lucky,” in which he plays an amputee, he learned how to make a Martini with one hand. “He wanted to be able to do it in a single take,” Soderbergh said.

After Driver and Cotillard had been soaked half a dozen times, Carax called a twenty-minute break. “Let’s do a tight twenty minutes,” Driver requested. He dried himself off for the next scene, in which the comedian wanders the ship alone, pummelled by waves and singing an ambiguous mantra, “There’s so little I can do.” By the end, he is crouched on the deck, his palms pressed to his ears.

They tried it again, and again. “Our timing was off,” Driver said after one take, wringing water from his black T-shirt. He and Carax went over the timeline of waves, music, boat rocking, and drunken stumbling. By now, Driver had been singing in a fake thunderstorm for five hours, and he was drenched. But he wanted more. “It doesn’t match up to the music,” he said of the boat movements, leaning over the railing.

Carax suggested that they had what they needed. “If you already have it, then fine,” Driver said, sounding agitated. “I’m trying to move on, but I don’t understand. And the timing is wrong.” He listened for a moment. “All right, then. I’m fine moving on. It’s just unsatisfying.”

Then they had a revelation: the boat choreography didn’t need to match the underscoring. They did the scene one more time, a cappella. Finally, for safety, they recorded a clean audio track of Driver’s singing. Wrapped in a towel, he sang his line repeatedly into a boom mike, alternately braying and mumbling, and then trailing off into a near-whisper. “There’s so little I can do,” he sang, dripping and determined. “There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do. There’s so little I can do.” ♦

David Fincher’s “Fight Club,” from 1999, has become a focal point for the exploration of postmodern masculinity, white-male resentment, consumerism, and gender relationships. Photograph from 20th Century Fox / Everett

David Fincher’s “Fight Club,” from 1999, has become a focal point for the exploration of postmodern masculinity, white-male resentment, consumerism, and gender relationships. Photograph from 20th Century Fox / Everett

Kyries on an excursion to the ruins of the Roman city of Dougga or Thuga, Tunisia

Kyries on an excursion to the ruins of the Roman city of Dougga or Thuga, Tunisia In Kef, Tunisia, walking towards Algeria

In Kef, Tunisia, walking towards Algeria