Bahadur Shah Zafar enthroned

Bahadur Shah Zafar ended up being the last of the Mughal emperors. Already along in years when the Uprising began, he became, due to the enormous symbolic power the Mughal Shahenshah still commanded, the reluctant leader of a revolution that, for even a younger and seasoned warrior – of whom he was neither – would have been a daunting force to control, command and direct. The original rebelling Hindu and Muslim sipahis (sepoys) had gravitated towards Delhi as the symbolic center of northern India. They were soon joined by random teams of jihadis, groups of what Dalrymple calls “Wahabbis,” though always in quotes so I don’t know quite know who he means, and the usual motley crew of Pashtuns down from Afghanistan that never miss a good fight if word of one reaches them. This alienated many Hindu factions in no good time and, bent as many of these groups were on plunder as much as Holy War, they ended up being as great a curse on the poor, long-suffering Delhiwallahs as any of the other players involved.

Zafar lived to see most of his family murdered. Of his, I believe, thirty-one sons – who participated in the uprising from roles of active leadership to not at all – only two survived: three teenagers were shot in the heart at point blank range; two of the more ’implicated’ sons of similar age were put before a firing squad ordered to fire low in the guts for maximum pain; the rest hanged – along with all the other male notables of his court, including Hindus. Certain amuck British officers seem to have spent days running around the ruins of the city, shooting anyone that looked even remotely “mirza”-like, or even Muslim, or just once rich. The hangings seem to have lasted for weeks, with a cessating intervention finally coming from London itself. Zafar was exiled first to the Andaman Islands and then to Burma, where he died in 1862.

It was the effective end of the Mughal aristocracy and the complete wiping out of an historic dynasty; a twentieth-century style liquidation of a social class; given the comparative dimensions of the societies involved, it was surely a purge of Bolshevik proportions and equally paranoid and crazy. Dalrymple artfully carries the consequences of these events into modernity for us.

******************************************************************************************

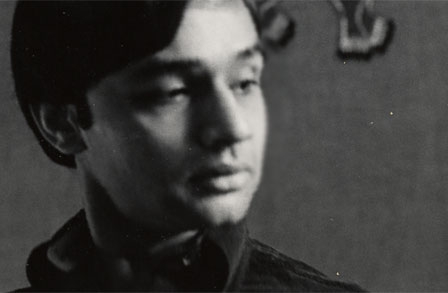

Zafar (below)

But while Zafar was certainly never cut out to be a heroic or revolutionary leader, he remains, like his ancestor the Emperor Akbar, an attractive symbol of Islamic civilization at its most tolerant and pluralistic. He himself was a notable poet and calligrapher; his court contained some of the most talented artistic and literary figures in modern South Asian history; and the Delhi he presided over was undergoing one of its great periods of learning, self-confidence, communal amity and prosperity. He is certainly a strikingly liberal and likeable figure when compared to the Victorian Evangelicals whose insensitivity, arrogance and blindness did much to bring the Uprising of 1857 down upon both their own heads and those of the people and court of Delhi, engulfing all of northern India in a religious war of terrible violence.

Above all, Zafar always put huge emphasis on his role as a protector of Hindus and the moderator of Muslim demands. He never forgot the central importance of preserving the bond between his Hindu and Muslim subjects, which he always recognized was the central stitching that held his city together. Throughout the Uprising, his refusal to alienate his Hindu subjects by subscribing to the demands of the jihadis was probably his single most consistent policy.

There was nothing inevitable about the demise and extinction of the Mughals, as the sepoys’ dramatic surge towards the court of Delhi showed. But in the years to come, as Muslim prestige and learning sank, and Hindu confidence, wealth, education and power increased, Hindus and Muslims would increasingly grow apart, as British policies of divide and rule found willing collaborationists among the chauvinists of both faiths. The rip in the closely woven fabric of Delhi’s composite culture, slowly widened into a great gash, and at Partition in 1947 finally broke in two. As the Indian Muslim elite emigrated en masse to Pakistan, the time would soon come when it would be almost impossible to imagine that Hindu sepoys could ever have rallied to the Red Fort and the standard of a Muslim emperor, joining with their Muslim brothers in an attempt to revive the Mughal Empire.

Following the crushing of the Uprising, and the uprooting and slaughter of the Delhi court, the Indian Muslims themselves also divided into two opposing paths: one, championed by the great Anglophile Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, looked to West, and believed that Indian Muslims could revive their fortunes only by embracing Western learning. With this in mind, Sir Sayyid founded his Aligarh Mohamedan Anglo-Oriental College (later Aligarh Muslim University) and tied to recreate Oxbridge in the plains of Hndustan.

The other approach, taken by survivors of the old Madrasa i-Rahimiyya, was to reject the West in toto and to attempt to return to what they regarded as pure Islamic roots. For this reason, disillusioned pupils of the school of Shah Waliullah, such as Maulana Muhammad Qasim Nanautawi – who in 1857 had briefly established an independent Islamic state north of Meerut at Shamli, in the Doab – founded an influential but depressingly narrow-minded Wahhabi-like madrasa at Deoband, one-hundred miles north of the former Mughal capital. With their backs to the wall, they reacted against what the founders saw as the degenerate and rotten ways of the old Mughal elite. The Deoband madrasa therefore went back to Koranic basics and rigorously stripped out anything Hindu or European from the curriculum.*

*(It was by no means a total divide: religious education at Aligarh, for example, was in the hands of the Deobandis.)

One hundred and forty years later, it was out of Deobandi madrasas in Pakistan and Afghanistan that the Taliban emerged to create the most retrograde Islamic regime in modern history, a regime that in turn provided the crucible from which emerged al-Qaeda, and the most radical and powerful fundamentalist Islamic counter-attack the modern West has yet encountered.

Today, West and East again face each other uneasily across a divide that many see as religious war. Jihadis again fight what they regard as a defensive action against their Christian enemies, and again innocent women, children and civilians are slaughtered. As before, Western Evangelical politicians are apt to cast their opponents and enemies as the role of “incarnate fiends” and conflate armed resistance to invasion and occupation with “pure evil.” Again, Western countries, blind to the effect their foreign policies have on the wilder world, feel aggrieved to be attacked – as they interpret it – by mindless fanatics.

Against this bleak dualism, there is much to value in Zafar’s peaceful and tolerant attitude to life; and there is also much to regret in the way that the British swept away and rooted out the late Mughal’s pluralistic and philosophically composite civilization.

As we have seen in our own time, nothing threatens the liberal and moderate aspect of Islam so much as aggressive Western intrusion and interference in the East, just as nothing so radicalizes the ordinary Muslim and feeds the power of the extremists: the histories of Islamic fundamentalism and Western imperialism have, after all, often been closely, and dangerously, intertwined. There are clear lessons here. For, in the celebrated words of Edmund Burke, himself a fierce critic of Western aggression in India, those who fail to learn from history are always destined to repeat it.

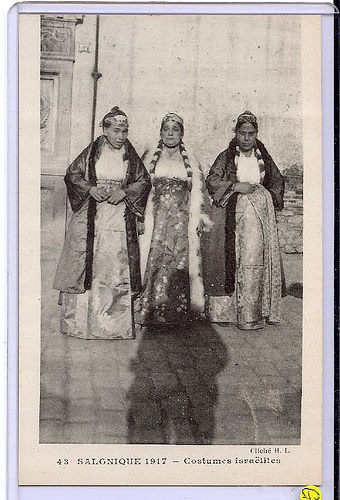

Zafar’s two surviving sons, who shared his Burmese exile with him.

****************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Agha Shahid Ali: “After Seeing Kozintsev’s King Lear in Delhi”

Lear cries out “You are men of stones”

as Cordelia hangs from a broken wall.

I step into Chandni Chowk, a street once

strewn with jasmine flowers

for the Empress and the royal women

who bought perfumes from Isfahan,

fabrics from Dacca, essence from Kabul,

glass bangles from Agra.

Beggars now live here in tombs

of unknown nobles and forgotten saints

while hawkers sell combs and mirrors

outside a Sikh temple. Across the street,

a theater is showing a Bombay spectacular.

I think of Zafar, poet and Emperor,

being led through this street

by British soldiers, his feet in chains,

to watch his sons hanged.

In exile he wrote:

“Unfortunate Zafar

spent half his life in hope,

the other half waiting.

He begs for two yards of Delhi for burial.”

He was exiled to Burma, buried in Rangoon.

Last known photograph of Bahadur Shah Zafar

**********************************************************************************************************************************

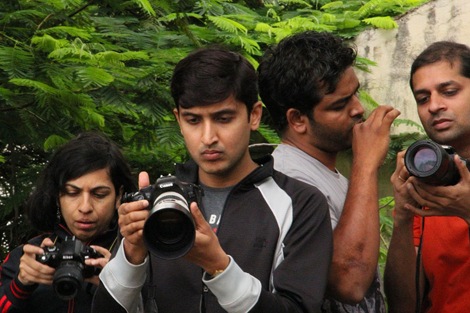

I’d like to heartily and gratefully thank Mr. Dalrymple (below) for his permission to reproduce such an extensive piece of his work. Usually permission is hard to obtain or you get no answer at all. When I wrote Mr. Dalrymple, however, he shot an email back at me within minutes saying nothing but: “Go for it.” Shukriya, kheyli moteshakeram, teshekur, and thanks again.

“After Seeing Kozintsev’s King Lear in Delhi” reprinted from The Veiled Suite: The Collected Poems by Agha Shahid Ali. English translation copyright © 2009 by Daniel Hall. With the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Watercolor of the Jama Masjid and old Delhi from 1852

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com