In a previous post, April 10th “A Dancing Girl,” I wrote about the ubiquity of Krishna-Radha imagery in Indian culture, from the obvious traditionally religious contexts to Bollywood cinema. Sudhir Kakar, Indian psychologist and I guess all around cultural critic has a very interesting analysis of the Krishna archetype in Indian cinema. He contrasts him, the playful phallic teaser, with the Majnun archetype, the distraught, longing lover (“majnun” means crazed in Arabic, the same Semitic root as “meshugeh” in Yiddish), setting up an interesting Hindu-Muslim interplay between the two:

“The Krishna-lover is the second important hero of Indian films. Distinct from Majnun,the two may, in a particular film, be sequential rather than separate. The Krishna-lover is physically importunate, what Indian-English will perhaps call the “eve-teasing” hero, whose initial contact with women verges on that of sexual harrassment. His cultural lineage goes back to the episode of the mischievous Krishna hiding the clothes of the gopis (cow-herdesses) while they bathe in the pond and his refusal to give them back in spite of the girls’ repeated entreaties. From the 1950s Dev Anand movies to those (and especially) of Shammi Kapoor in the 1960s and of Jeetendra today, the Krishna-lover is all over and all around the heroine who is initially annoyed, recalcitrant, and quite unaware of the impact the hero’s phallic intrusiveness has on her. The Krishna-lover has the endearing narcissism of the boy in the eve of the Oedipus stage, when the world is felt to be his “oyster.” He tries to draw the heroine’s attention by all possible means – aggressive innuendoes and double entendres, suggestive song and dance routines, bobbing up in the most unexpected places to startle and tease her as she goes about her daily life. The more the heroine dislikes the hero’s incursions, the greater his excitement. As the hero of the film Aradhana remarks, “Love is only fun when the woman is angry.”

“For the Krishna-lover, it is vital that the woman be a sexual innocent and that in his forcing her to become aware of his desire she get in touch with her own. He is phallus incarnate, with distinct elements of the “flasher” who needs constant reassurance by the woman of his power , intactness, and especially his magical qualities that can transform a cool Amazon into a hot, lusting female. The fantasy is one of the phallus – Shammi Kapoor in his films used his whole body as one – humbling the pride of the unapproachable woman, melting her indifference and unconcern into submission and longing. The spirited, androgynous virgin is awakened to her sexuality and thereafter reduced to a groveling being, full of a moral masochism wherein she revels in her “stickiness” to the hero. Before she does so, however, she may go through a stage of playfulness where she presents the lover with a mocking version of himself. This in Junglee, it is the girl from the hills – the magical fantasy-land of Indian cinema where the normal order of things is reversed – who throws snowballs at the hero, teases him, and sings to him in a good-natured reversal of the man’s phallicism, while it is now the hero’s turn to be provoked and play the recalcitrant beloved.”

— Intimate Relations: Exploring Indian Sexuality, Sudhir Kakar

–

Bollywood classicists will probably object to my not using one of the above-mentioned actors as a movie clip example, but I’ve chosen to use recent meteor-hottie Imran Khan instead:

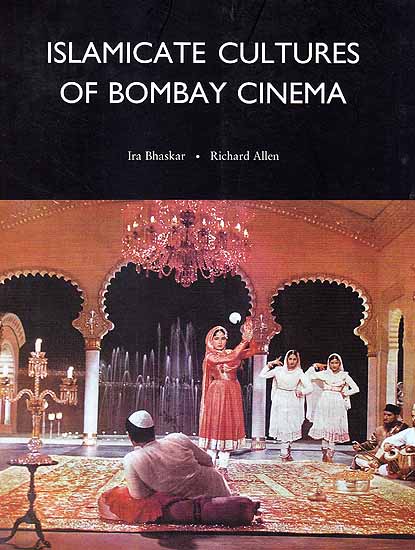

Not that Imran Khan… No relation to Shahrukh Khan either or Salman Khan, but the nephew of Aamir Khan — just in case you doubted how nepotistic Bollywood is, how full of super-size Khan egos it is, or how disproportionately Muslim the industry is, a fact that usually remains unspoken. Other than his still teenage swagger, which the other Khans are getting a little too old to pull off, I think Imran is so perfect in the role of this archetype because he has those exaggeratedly large, murti-like* eyes and eyebrows that so many Indians have and have such deep religious significance and symbolism. “Darshan,” or the viewing of a deity, is usually centered on the eyes — on a visit to any temple one will usually find at least one devotee staring endlessly into the god’s eyes — and Hindus believe that the deity’s energy does not come to reside in an image until that very final moment when its pupils are painted in.

Anyway, here’s Imran with his Gopis, in the title number of the 2010 I Hate Luv Stories, playing the Dusky One to perfection (though as in Kakar’s classic trajectory, he’s later humbled into the Majnun lover):

And for those old-schoolers, here’s SRK, perhaps the central casting expert at the type, in the wedding scene from Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, the wedding he’s impudent enough to crash because he’s smitten with the bride’s sister and shows up to hit on her.

*”Murti” is the image of a deity in Hinduism, any image: statue, painting, drawing, cheap print from the kiosk. Obviously I don’t use the word “idol,” with its reek of monotheist condescension and demonization, as I generally consider monotheism — all of them — to be something of a plague and a great historical tragedy. We’ll just have to do the best we can with what we have for now.

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–