–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

Tags: Christianity, Christmas, Yalda, Zoroastrianism

In response to : “Syria, Russia, ISIS and what to do about everything“:

“i agree with you that “no peace with assad” is bullshit rhetoric—even though, morally, i agree with it—but you’re right. and that kind of self-righteous sloganeering has really hurt the syrian opposition.”

Hurt them in the sense that it’s an ultimatum in which you get stuck and then can’t get yourself out of, even when an opportunity presents itself? Because once you’ve issued that kind of statement, the all important “face-giving” becomes impossible unless you get exactly what you want?

“…but the phrase “i can see no great tragedy” in an assad/russia protectorate struck me as callous. i think perhaps because of that phrase “no great tragedy.” talk to the refugees. seek them out, they won’t be hard to find, and a lot of them speak english. you will see great tragedy, on a great scale, and you will see why leaving him in power is in fact a tragedy. (you’ve seen the caesar pictures, right? there’s a lot to say about the horrors of the regime, but the pictures pretty much say it all.) what will strike you, if you talk to the refugees, is that this is very much a sunni tragedy. Have you read Deb Amos’s book The Eclipse of the Sunnis? it’s a prescient look at the disenfranchisement of the sunni people (not leaders, that’s a different matter). she does a good job of setting the stage for the massive rage, displacement, and revanchism that’s happening now with isis. it’s really important to understand the rural poverty and genuine grievance of the sunni majority in syria. likewise, the supremacism of the minority elites, and how it expresses itself: through a sneering contempt for peasants, through disastrous economic policies—read Suzanne Saleeby’s Jadaliyya piece on the drought, it’s great—and through a kind of neoliberal bootstrap rhetoric from the regime, aimed at the sunni masses, that is truly savage and surreal.”

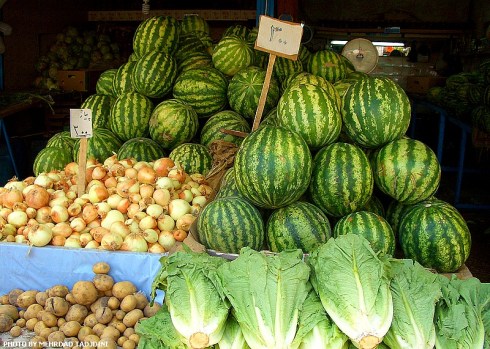

Really? Did I really have to say “no greater, horrendous, nightmarish, tragedy” for what I wrote to not have been considered callous? Do you think I don’t find and seek out refugees in Athens? They’re everywhere here too — not just in Mytilene or Idomene – and that I don’t talk to them? They’ve taught the vendors at the farmers’ markets some necessary Arabic: “Wahad euro, wahad kilo,” said one the other day, a farmer from Corinth, like a good Greek who will learn any language with lightning speed if it’s about making a buck, or just satisfying his curiosity about who this new foreign person is or where he’s from, to a hijabbed woman as she perused his stuff, adding, “κι αν δε σ’αρέσει πήγαινε αλλού,” “and if you don’t like it you can go somewhere else.” To which she replied: “Θα πάω αλλού” “I’ll go elsewhere” with a smile. And then they bargained some more and she bought quite a bit of stuff from him and ended up being kinda chums. OK, two Levantines who will immediately learn any language when it comes to a buck… Talked to her afterwards; she’s learned that Greek in the month she’s been in Athens, Sunni from somewhere near Aleppo, estimates that nearly half her extended family, including her husband, is dead or scattered all over the world at this point.

I know she just wanted the war to end, with or without Assad was not important to her and I got the feeling it never was, and she swears she’s never going back. No matter what peace they put in place, because her country “doesn’t exist anymore.” And what I meant by “no great tragedy” is that the democraticness of Assad or the Russians might have to take a back-seat priority-wise right now. You hear from everywhere, even from among the most passionately anti-Assad Sunnis, (“They are animals and they are animals; Syria go from bad to more bad…” said another Syrian kid I was talking to on the subway, echoing the Saddam-was-bad-but-this-is-worse you hear from so many Iraqis), that even leaving Assad in place at this point would be preferable to continuing to wage the war as it’s being waged by all sides. If a Russian-backed Assad can bring a solid, frigid peace to that western, most populated, most urbanized strip of the country right now, do we have the right to be “choosers”?

I understand that this may be “very much a Sunni tragedy,” though I’d be terribly cautious about speaking like that – like Syria is any one group’s tragedy over another’s. And “revanchism,” S., like the prefix “re-“ indicates, comes from somewhere. Yes, I’m Greek, and technically Orthodox; yes, I have a special affinity for Shiism, for Turkish Alevis and Bektaşis and for minorities in the Muslim world everywhere, groups whose beliefs and their affective nature seem to undermine mainstream Islam’s arid legalism and moralism. But when the Western media started explaining to an ignorant Europe and North America who “Assad’s” Alawites were, the first analogy that came to my mind were Lebanese Maronites, whom that same Western media, thirty years earlier, especially any left-leaning kind, had portrayed as the purest, most vicious and by far most responsible for the Lebanese Civil War group at that time — even as it was discovering these newly horrid Shiite “terrorists” in the south and their suicide bombers. (Yugoslavia and Serbs still come to mind; choose a bad guy and run with it ’cause it’s a simple story that’ll sell). And maybe if you had cut the 70s and 80s out of Lebanese history and spliced them into a specially edited documentary version of that history, then maybe Maronites do carry a special responsibility.

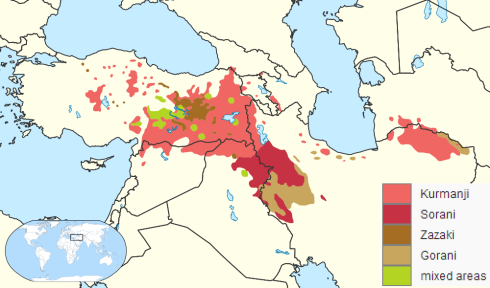

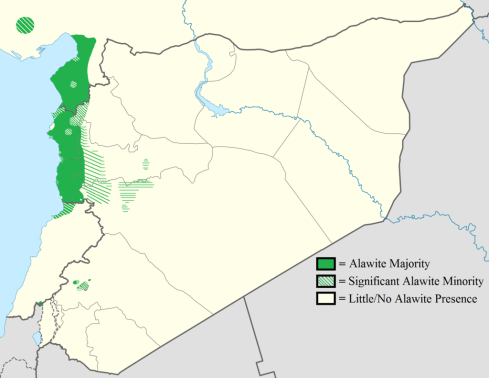

But you can’t look at an ethno-religious map of the Levant and Mesopotamia, find all non-Sunni and non-Muslim minorities concentrated in the safety of the region’s most inaccessible highlands and not wonder why. Or find them suffering as a downtrodden, peasant – practically serf – population in the south of Iraq and the south of Lebanon and not wonder again.

And if members of those groups chose a different fate and gathered through history into the safety of numbers in cities, where, because they were excluded from access to other forms of power by the centuries of Sunni hegemony, they acquired the survival skills necessary: the mercantile and financial knowledge; the language skills; the ease with which one emigrates and leaves a city over an ancestral village where the ties are stronger, and knowledge of the broader world that creates and the émigré networks throughout the world it forges, which then reinforce your mercantile and financial strength back home…all of which generally make you more ready for modernity when it comes knocking at the door… To accuse those groups, whether in Syria today, or Lebanon in the 80s, or in the Balkans and Anatolia in the Ottoman past, of ‘elite minority supremacism’ comes a little uncomfortably close to blaming Jews for anti-semitism. Your explanation of why Christians don’t number among the refugees because they have a more accessible émigré network that takes them straight to Europe or North America may have sounded callous to me too — like leaving their country doesn’t hurt them. And if they do — like Jews — have those networks, good for them. It’s called survival.

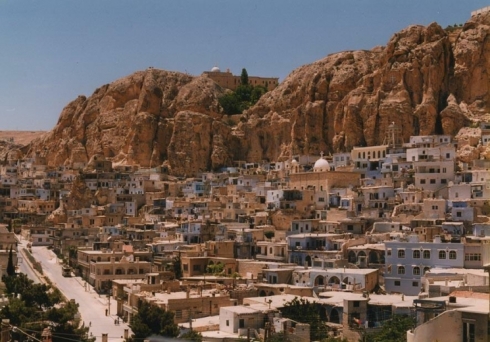

In any event, you don’t even have to look so many centuries back, just at the vicious outbreak of Sunni anti-Christian violence, which first made “our sweet mother France” step into the Syro-Lebanese scene in the mid-nineteenth century, to see why an Aleppo Armenian or a Syrian Christian in Damascus is not thrilled with the idea of a largely Sunni revolt against Assad. And I don’t condone it, like I don’t condone it even in a poor, old, lonely Greek lady in Istanbul when she talks about the rural Turks who have taken over “her” city as barbarians, but I, you, we shouldn’t forget that there’s probably a DNA-inscribed fear of the rural “masses” written on these people’s genetic make-up. ‘Cause when the killing came, it wasn’t the Sunni leaders or paşas or generals even sitting at their desks who did it; it was their neighbors.

And especially — if all this is about Sunni anger at not being on top anymore, like maybe most Muslim anger in the 20th century is about not being on top anymore — I’m sorry, callous or not — my sympathies are limited.

“re: leaders, what about abdul-karim qassem? what about faisal? what about abdelkrim al-khattabi? what about rashid rida and the 1920 Syrian constitution? i would read libby thompson’s book on constitutionalism on the middle east (justice interrupted), and ali allawi’s biography of faisal (faisal of iraq) and anything on abdelkrim (not sure if there’s been a good biography of him, but if there isn’t there should be) before weighing in on this so definitively.”

I think when I say the Ba’athists that followed the Hashemites in Iraq, it’s clear I’m talking about Faisal. Ok, maybe Ba’athists per se didn’t follow immediately on the Hashemites in Iraq. But abdul-karim qassem, S? Are you for real? The general who deposed Faisal’s grandson or greatgrandson, had the royal family shot, played around with an attempt at a constitution that got nowhere and then essentially resparked animosity with the Kurdish north that the Ba’athists only took to the next level? This is the model of the democratic leader who I’m supposed to think was going to bring true constitutionalism to Iraq? abdelkrim al-khattabi, I don’t know that I can consider anything but the leader of an ethnic rebellion against the French, since he didn’t get a chance to do much else and I don’t know that if he had succeeded, his new order wouldn’t have involved a potent element of Berber “revanchism” against Morocco’s Arab-speaking population. Rashid Rida I know nothing about, so I won’t cheat and assail you with Wikipedia info. And yet Wiki calls him a Salafi. Ok. I’ll get Libby Thomson’s “Justice Interrupted” – it genuinely sounds like what I’ve always needed to read — and we’ll talk.

“also, finally: i would cool it with the “mesa girls” thing. i know exactly the type, and they bug the shit out of me too, but the phrase is bad because a: the phenomenon you’re describing is just as common among mesa men, if not more so, than women, and b. it makes you sound petty, like you hit on some mesa scholar, and she rejected you, and now you won’t let it go. I KNOW that’s not what happened, but that’s how it sounds, and it undercuts your knowledge and the point that you’re making.”

Point taken, S. And I’m glad you “KNOW” that what happened wasn’t my hitting on some chick at a MESA conference and not being able to deal with the blow off. Because what actually happened was far worse. What happened was that people I was very close to and considered friends for life just severed ties with me, because after 2001 and/or 2003 I just wouldn’t fall in line with their party policy of finding “explanation” for any and all expression of Arab anger, no matter what form it took. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise. All through the years of our friendship, the sense that I wasn’t quite “correct” enough ran as an undercurrent of disapproval in their attitudes toward me. And, like I say, these types weren’t even Middle-Eastern born, weren’t even ethnic-Americans who learned Arabic at home. They were super-assimilated types that discovered their “Arab-ness” as undergrads and had to learn the language in college. I was more an Arab than any of them. And when we all met in Istanbul because I was doing the fieldwork for a documentary on the Greeks of the city that never got anywhere, the one who was most obnoxious to me and suspect of my “Christian” academic interests was the only one regionally-born, but not even Muslim, but from a very prestigious Lebano-Palestinian intellectual lineage of Protestant converts who apparently had to treat me that way to keep her claim to her clan’s laurels fresh. So when the early 2000s came around I had to either be silenced or cut off, and since I wouldn’t accept the former it was the latter. And it made me very angry, in the vein of: “Look at us, you assholes, you can’t find a way to accept the differently inflected views of someone essentially on your side, and you expect any-body to be able to productively communicate in ‘our parts.’” Plus, it hurt, personally, and I’m Albanian and a past master at keeping and nursing a grudge — an often violent one — and don’t forgive shit like that. I might lay off the “MESA girls” stuff – but I’ll still be lying in wait.

“re: hezbollah, that’s a longer conversation. you’re right about their military prowess, but to say that they’re the only thing keeping lebanon stable is a statement i wouldn’t make.”

I don’t know enough about Lebanon to make a statement like that: “…the only thing keeping Lebanon stable…” In fact, that’s not what I said. I do kind of think that, as unfortunate as both phenomena might be or have been as the source of Lebanese “peace,” that it was the Syrian occupation on the one hand and Hezbollah’s very intelligent (or brutally intelligent) conversion of their military prowess into political hegemony that essentially stopped the ugliest part of the ugliness in Lebanon. Answer that. Isn’t that kinda what happened? What the always creative Lebanese — a country and people I love with an unusual urgency though I’ve never even been there – did with those two — one north and one south – factors afterwards is another question. But wasn’t it the two of them together that kind of put a stop to the the hellish laying waste of the place?

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

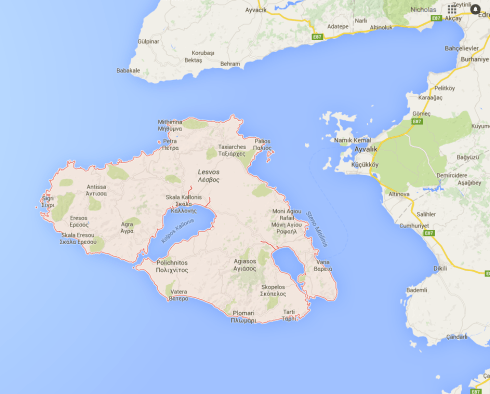

It was Mytilene’s (Lesbos) karma, I thought, from the beginning of the refugee crisis, to become the portal for the whole tragic flood of humanity that’s entering Europe right now. At the time of the ugly and brutal Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey of their respective minorities that was decided by the Treaty of Lausanne and began in 1923, Mytilene was the only Greek island off the Aegean coast that had a large number of Muslims, probably more then one quarter of its population. Chios (Sakız), and Samos had very few, almost none in the case of Samos, while the islands further south, the Dodecanese, had already been given to the Italians by the victorious Entente/Allies and so the ancestors of the some 5,000 Turks (Greece’s Turkish minority that we tend to forget about) that still live in Kos and Rhodes were exempt.

Across exactly from Mytilene is the Turkish town of Ayvali (Ayvalık). Ayvali was one of those products of the Ottomans’ improvisatory policies for managing the multiple ethnic and religious corporate groups that constituted the empire, and usually worked; in the 18th century, the coast of the Anatolian Aegean being underpopulated and underutilized economically, a grant was given to Greeks to settle there that didn’t just encourage Greeks, but excluded Muslims from settling there, to make the area even more attractive for Greek settlers.*

And very soon, Ayvali grew, out of its seafaring activities and the fertility of its hinterland, into a prosperous and what is, architecturally, still a beautiful small Greek city, the object of much nostalgia in the Greek genre of Anatolian martyrology, but more, the symbol of what Patricia Storace calls “the voluptuous domesticity” that Greeks associate with their former paradisiacal life on the Aegean coast.

[It’s also made Ayvali, the neighbouring island of Cunda, Tenedos and Imvros to some extent, newly fashionable for White Turk hipster tourists, since their parents’ generation didn’t get a chance to turn it all into Bodrum or Benidorm. They’re the Aegean coast equivalent of Pera/Karaköy and like neighborhoods in Istanbul.]

So the two regions came to fit into each other like a Yin/Yang symbol, and when the Exchange came, most Ayvali Greeks were settled in Mytilene, while the Turks of the island were shipped just across the water – the often treacherous channel were so many refugees today have drowned (it’s a great error – popular and tourist-based — to see the Aegean as a benign sea), and settled in Ayvali and its neighboring villages.**

Mytilenioi, a population of around 80,000, in a country sunk into the deepest economic pit of any country in the European Union, have seen over 400,000 refugees pass through their island in 2015. And yet, despite a few outbreaks, the islanders’ acceptance of this flood of humanity has been exemplary: full of patience, humanity and humor even – as Roger Cohen reported: “Battered Greece and Its Refugee Lesson“ — with a deep empathy that I had thought from the beginning was due partly to so many of the islanders’ descent – only one or two generations – from refugees themselves.

When I’d say so here in Greece, many responded to me with the usual Greek cynicism: our deepest, most tragic flaw, that no one is ever doing anything in good faith. Yet at least one Greek journalist and blogger, Michalis Gelasakis,had the same idea, posting this photo of old Greek women on Mytilene cradling and feeding the baby of a Syrian refugee woman:

“Γιαγιάδες στη Μυτιλήνη ταΐζουν το μωρό μιας προσφυγοπούλας. Πιθανό και οι ίδιες να είχαν φτάσει κάπως έτσι στις βορειοανατολικές ακτές του νησιού.”

“Γιαγιάδες στη Μυτιλήνη ταΐζουν το μωρό μιας προσφυγοπούλας. Πιθανό και οι ίδιες να είχαν φτάσει κάπως έτσι στις βορειοανατολικές ακτές του νησιού.”

“Grandmothers in Mytilene feed the baby of a refugee woman. Likely themselves to have arrived like this in North-East Coast of the island.”

And now, to confirm my own sentiments, comes this stunning article, “Be like Water” in Guernica by Annia Ciezadlo, a Beirut-based journalist, that weaves together the Greco-Turkish Population Exchange, Indian Partition, Mytilene’s place in the current refugee crisis, Homer and ancient concepts of hospitality, all in one tender, moving piece:

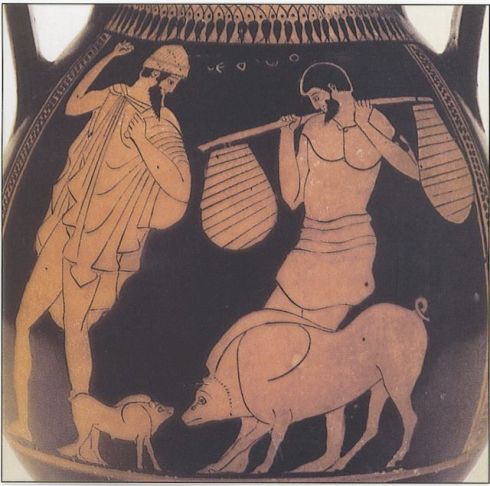

“Philoxenia: love for the stranger, the traveler, the guest. Who might be a god or goddess in disguise. Or Odysseus, returning from his travels in the guise of a beggar in order to test the loyalties of his servants.”

“Old man, the dogs were likely to have made short work of you, and then you would have got me into trouble. The gods have given me quite enough worries without that, for I have lost the best of masters, and am in continual grief on his account. I have to attend swine for other people to eat, while he, if he yet lives to see the light of day, is starving in some distant land. But come inside, and when you have had your fill of bread and wine, tell me where you come from, and all about your misfortunes.”

[My emphasis]

—Eumaeus, the Syrian [how did she find this idea?], to the disguised Odysseus; The Odyssey, Book 14

I know that the people of Mytilene – and their “philoxenia” or even more, their “philotimo,***” have done us proud as Greeks, and deserve a collective Nobel peace prize for 2015, while the rest of Europe has acted more like Eumaeus’ dogs.

Read Ciezadlo’s beautiful tapestry of a piece – now…

************************************************************

Greek refugee ship leaving Smyrna. September, 1922. Image source: Drexel University College of Medicine, Archives and Special Collections.

Greek refugee ship leaving Smyrna. September, 1922. Image source: Drexel University College of Medicine, Archives and Special Collections.

Be Like Water

By Annia Ciezadlo

December 15, 2015

The Nonviolent State of Iraq and Syria. The Republic-in-Motion of Lovers Not Fighters. The Government-in-Exile of People Who Just Want to Go to School.

“I came to Mytilene, believe it or not, for vacation…”

The rest here.

********************************************************

* Yeah, the Ottomans did odd shit like this, to keep everybody happy and for the most part it worked. Like Ayvali and its environs, for example, in Istanbul in the 17th century the Porte granted the mostly Chian shipyard workers from the tershana in Hasköy on the Golden Horn/Keratio, the right to establish a village around the pre-existent shrine of St. Demetrios on the hilltop which the gulley up through Dolapdere led to, and where no Muslims, weirdly, were allowed to settle. This was the nucleus out of which the legendary Greek neighborhood of Tatavla grew, and which, due to its rough, working class character, was an intimidating place for Muslims to enter until the end of the Empire. Except for its famous Carnival, when everyone was allowed.

The same would happen in highland regions of Greece, Epiros especially — where remittances from emigrant locals provided the wealth to pay for it — where autonomous privileges were bought from the Ottoman authorities in return for a modest amount of self-government and the right to not have Muslims settle there and not be subject to Islamic proselytizing of any sort — violent or otherwise. “…και παππού σε μέρη αυτόνομα μέσα στην τουρκοκρατία…” as Savvopoulos once sang.

** The truth is that refugees from neighboring Mytilene were probably outnumbered by Cretan Turks in Ayvali, like along much of the Aegean coast left empty by departing Greeks, along with Ayvali, Smyrna itself and the neighboring peninsula of Karaburna. The irony here is that many of the Mytilene Turks that came were Turkish-speaking, while the massive flood of Cretan Turks spoke Greek, so that much of the Aegean coast remained Greek-speaking, albeit Greek of a markedly different dialect, until a couple of generations or so ago. And despite the disappearance of the language, of all the Turkish exchangees, it’s Cretan Turks who have most preserved a solid identity and group consciousness.

*** Philotimo: a complex word I’ll have to explain in another post, though I give it a go here:

“Honor” is a bad translation for “φιλότιμo,” which means honor and amour propre and sense of dignity and reciprocity, all in one complex structure of emotions and social acts. Basically, “philotimo” is the sense of self-respect that’s intimately tied up with the upholding of your obligations to others that held Greeks together for centuries. All readers here know I’m a fanatic opponent of reading Classicizing virtues – or Classical anything — into Neo-Greek society, but the importance of “philotimo,” I feel, even if just discursive, even if only in its lapses, is a millennia-long constant.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

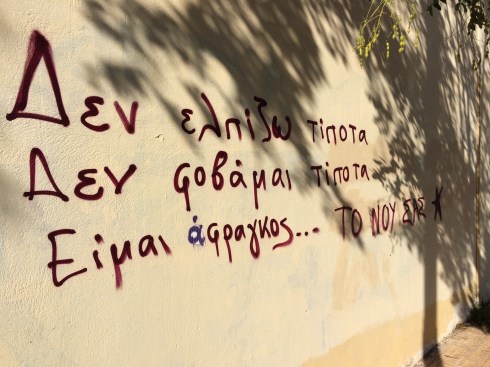

Athens is a city literally covered in graffiti. Whether that adds to its cement ugliness or alleviates it is one’s aesthetic choice I guess. I know it’s the physical marker of a deeply urban, intensely verbal culture — just the way the history books describe us — the verbal urge so intense that you cover your city in writing — and even if you consider it pure defacement, it can’t be written off as anything but as one of Athens’ essential constitutive elements.

Mostly it’s by kids who are, or maybe just consider themselves, “anarchists” — though their pointed, often witty, often absurdist undermining of the Greek political power structure’s self-importance, incompetence and viciousness make you grudgingly respect them. Like this one:

“ΜΠΑΤΣΟΙ ΘΑ ΣΑΣ ΦΑΝΕ ΤΑ ΠΑΙΔΙΑ ΣΑΣ” — “PIGS [COPS], YOU’LL BE EATEN BY YOUR CHILDREN” — like an image out of Greek mythology.

Lately, though they had gone away for a while, there’s been a profusion of pro-immigrant graffiti and posters, in support of welcoming the 1,000,000 refugees that have come into Europe this year, some three-quarters of them, yes, 750,000, through Greece, the EU country least in a position economically to shoulder and support them and yet the one that has done so with almost no racist or nationalist backlash, but with a popular pride, Homeric even, in being the ones to host the guest, though so least able to. This one below is about Albanians:

“ΕΙΜΑΣΤΕ ΟΛΟΙ ΑΛΒΑΝΟΙ ” — “WE’RE ALL ALBANIANS” — I was surprised to keep seeing this one; it had been popular in the 90s when, with the fall of communism, Greece was flooded with Albanians, they say 250,000, but their assimilation, or rather, maintenance of a double identity, is so deep that I’m sure it was more than a million and now there are really no cultural or linguistic borders between the two countries anyway; both have become a Balkan form of the American Southwest. It’s probably been taken out of the mothballs for the current immigration flood. What you see more often now is: “ΕΙΜΑΣΤΕ ΟΛΟΙ ΠΡΟΣΦΥΓΕΣ” — “WE’RE ALL REFUGEES.” I had walked by this one for a few days and put off taking a photo of it, so someone who didn’t agree had come by and crossed out “Albanians.” Greek conversations are like that: a super smart idea will get thrown, and everyone else’s idea — super-smart or not — will respond, or not really, just shoot off its own reaction, till it turns into a shootout with shit bouncing around all over the walls, that never really gets anywhere. From elementary school playgrounds to Greek parliament, this is how people talk.

Some, of an obviously Freudian tone, seem to be by students of the Athens University’s School of Psych:

“Ο ΦΟΒΟΣ ΤΡΕΦΕΙ ΤΟ ΦΑΣΙΣΜΟ, Ο ΕΡΩΤΑΣ ΤΗΝ ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ”– “FEAR BREEDS FASCISM, EROS FREEDOM”

My favorite so far has been one that playfully strums on all the fears or possibly scary manifestations of the current, deep, EU-exacerbated, impoverishing economic crisis the country is facing, (25% unemployment, 50% youth unemployment, a suicide rate that’s gone up by 36%, and no end in sight…) and does so by taking a witty swipe at my most detested Greek writer, the Cretan Kazantzakis, and his faux-epic, imitation-Russian philosophical heroism. (Being Cretan, I guess you can’t help it.) It’s a play on one of his most popular aphorisms: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.” You can get this piece of existential brilliance on a refrigerator magnet or painted ceramic plate in a tourist shop on any Greek island. Including Crete, of course.

This version, however, says:

“Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα… Δεν φοβάμαι τίποτα… Είμαι άφραγκος… ΤΟ ΝΟΥ ΣΑΣ” — “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I’m penniless. SO WATCH IT.”

Some are just vulgar for vulgarity’s sake, like this one, which is probably about soccer team rivalry (what else could be more vulgar? anywhere?) and disses my ‘hood, Pagkrati, but in Latin characters so that they could be sure that I don’t know who — the neighboring hooligans from Zografou? — would understand:

“PAGKRATI — YOU CUNTS”

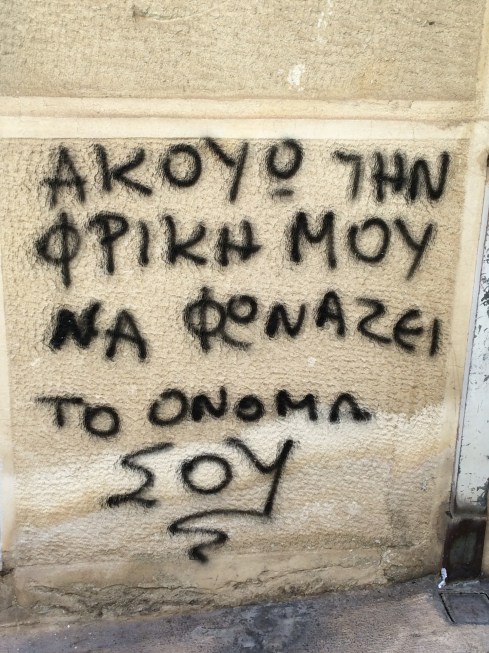

Some are startlingly tender in their eroticism:

“ΑΚΟΥΩ ΤΗΝ ΦΡΙΚΗ ΜΟΥ ΝΑ ΦΩΝΑΖΕΙ ΤΟ ΩΝΟΜΑ ΣΟΥ” — “I HEAR MY HORROR CALLING OUT YOUR NAME.”

Some sweeter and gentler in their desperation:

“ΣΕ ΘΕΛΩ ΠΟΛΥ…N” — ” I WANT YOU – A LOT…N”

More to come.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

I’m late on my New Yorker reading. I generally detest reading on line and anyone who tells me they can and don’t mind are generally people — under 40 — who really don’t really read anything, or anything long, or anything worth calling reading. And the New Yorker is especially galling in its PDF-type format and the general impossibleness it makes to look up old articles, etc… They’re insufferable.

So I have my New Yorkers sent to me in precious print care packages from New York while I’m in Athens. So I’m behind — just done with the September 28th issue — which has also, so far, saved me from that moment of truth when they might possibly publish the “post-Paris-attacks, guilty post-colonial, sappy, poor alienated youth from the banlieue” piece which would make me cancel my subscription and never touch another issue in my life.

Instead I just finished James Wood’s beautiful piece on Primo Levi. Don’t have that much to say right now. Only that those parts of Levi’s work that he reviews and that moved me most were the most perhaps pettily personal ones: not the grand, existential pieces about the camps and what is a man and survival, but the simple ones of what it means to be a Jew, where you’re maybe a Jew because — and only because — the society around you will always see you as one.

This splendid piece on relatives who married goyim and his uncle’s love of prosciutto:

“Uncle Bramín falls in love with the goyish housemaid, declares that he will marry her, is thwarted by his parents, and, Oblomov-like, takes to his bed for the next twenty-two years. Nona Màlia, Levi’s paternal grandmother, a woman of forbidding remoteness in old age, lives in near estrangement from her family, married to a Christian doctor. Perhaps“out of fear of making the wrong choice,” Nona Màlia goes to shul and to the parish church on alternate days. Levi recalls that when he was a boy his father would take him every Sunday to visit his grandmother. The two would walk along Via Po, Levi’s father stopping to pet the cats, sniff the mushrooms, and look at the used books:

“My father was l’Ingegnè, the Engineer, his pockets always bursting with books, known to all the salami makers because he checked with a slide rule the multiplication on the bill for the prosciutto. Not that he bought it with a light heart: rather superstitious than religious, he felt uneasy about breaking the rules of kashruth, but he liked prosciutto so much that, before the temptation of the shop windows, he yielded every time, sighing, cursing under his breath, and looking at me furtively, as if he feared my judgment or hoped for my complicity.”

A friend of mine from New York wrote to me after I posted: “This is the saddest story: Syria’s last Jews leave — By Sami Moubayed, Special to Gulf News,” which talks about members of the family, who weren’t given an Israeli visa because they were married to Muslims:

“I am Mariam and she is me. The weight of history. It doesn’t matter whether I choose to identify with her, I am identified with her by others, that’s why we are the same. Just a different place. I can only wonder what Gilda is feeling. Probably terrified she will be found out.”

“…terrified she will be found out.” A big difference, and not — ninety years into what we thought would be a better world — because she had an insatiable craving for prosciutto.

I’ve had “The Periodic Table” sitting on my shelves for years and never, ever looked at it, never knew that it was a logging of each element on the table and its correspondence to something but mostly someone in Levi’s personal life. They’re beautiful, for all sorts of reasons:

“Zinc, zinco, Zink: laundry tubs are made of it, it’s an element that doesn’t say much to the imagination, it’s gray and its salts are colorless, it’s not toxic, it doesn’t provide gaudy chromatic reactions—in other words, it’s a boring element.”

Except now, more than ever, it reminds one of Paris.

Or:

Giulia Vineis, “full of human warmth, Catholic without being rigid, generous and disorderly”

And one with a personal resonance for me:

As a teen-ager at the Liceo D’Azeglio, Turin’s leading classical academy, he stood out for his cleverness, his smallness, and his Jewishness. He was bullied, and his health deteriorated. His English biographer Ian Thomson suggests that Levi developed a sense of himself as physically and sexually inadequate, and that his subsequent devotion to robust athletic pursuits, such as mountaineering and skiing, represented a self-improvement project. Thomson notes that, in later life, he recalled his mistreatment at school as “uniquely anti-Semitic,” and adds, “How far this impression was coloured by Levi’s eventual persecution is hard to tell.” But perhaps Thomson has it the wrong way round. Perhaps Levi’s extraordinary resilience in Auschwitz had something to do with a hardened determination not to be persecuted again… [emphasis mine]

…The most moving chapter in “The Periodic Table” may be the one titled “Iron.” It recalls a friend, Sandro, who studied chemistry with Levi, and with whom he explored the joys of mountain climbing. Like many of the people Levi admired, Sandro is physically and morally strong; he is painted as a headstrong child of nature out of a Jack London story. Seemingly made of iron, and bound to it by ancestry (his forebears were blacksmiths), Sandro practices chemistry as a trade, without apparent reflection; on weekends, he goes off to the mountains, to ski or climb, sometimes spending the night in a hayloft.

Levi tastes “freedom” with Sandro—a freedom perhaps from thinking, the freedom of the conquering body, of being on top of the mountain, of being “master of one’s destiny.” Sandro is a powerful presence on the page; aware of this, Levi plays his absence against his presence, informing us, in a beautiful lament at the end of the chapter, that Sandro was Sandro Delmastro, that he joined the military wing of the Action Party, and that in 1944 he was captured by the Fascists. He tried to escape, and was shot in the neck by a raw fifteen-year-old recruit. The elegy closes thus:

“Today I know it’s hopeless to try to clothe a man in words, make him live again on the written page, especially a man like Sandro. He was not a man to talk about, or build monuments to, he who laughed at monuments: he was all in his actions, and when those ended nothing of him remained, nothing except words, precisely.”

***********************************************************

And the whole article….

A Critic at Large September 28, 2015 Issue

The Art of Witness

How Primo Levi survived.

By James Wood

Much writing by Holocaust survivors does not quite tell a tale, but Levi had a powerfully narrative imagination.

Primo Levi did not consider it heroic to have survived eleven months in Auschwitz. Like other witnesses of the concentration camps, he lamented that the best had perished and the worst had survived. But we who have survived relatively little find it hard to believe him. How could it be anything but heroic to have entered Hell and not been swallowed up? To have witnessed it with such delicate lucidity, such reserves of irony and even equanimity? Our incomprehension and our admiration combine to simplify the writer into a needily sincere amalgam: hero, saint, witness, redeemer. Thus his account of life in Auschwitz, “If This Is a Man” (1947), whose title is deliberately tentative and tremulous, was rewrapped, by his American publisher, in the heartier, how-to-ish banner “Survival in Auschwitz: The Nazi Assault on Humanity.” That edition praises the text as “a lasting testament to the indestructibility of the human spirit,” though Levi often emphasized how quickly and efficiently the camps could destroy the human spirit. Another survivor, the writer Jean Améry, mistaking comprehension for concession, disapprovingly called Levi “the pardoner,” though Levi repeatedly argued that he was interested in justice, not in indiscriminate forgiveness. A German official who had encountered Levi in the camp laboratory found in “If This Is a Man” an “overcoming of Judaism, a fulfillment of the Christian precept to love one’s enemies, and a testimony of faith in Man.” And when Levi committed suicide, on April 11, 1987, many seemed to feel that the writer had somehow reneged on his own heroism.

Levi was heroic; he was also modest, practical, elusive, coolly passionate, experimental and sometimes limited, refined and sometimes provincial. (He married a woman, Lucia Morpurgo, from his own class and background, and died in the same Turin apartment building in which he had been born.) For most of his life, he worked as an industrial chemist; he wrote some of his first book, “If This Is a Man,” while commuting to work on the train. Though his experiences in Auschwitz compelled him to write, and became his central subject, his writing is varied and worldly and often comic in spirit, even when he is dealing with terrible hardship. In addition to his two wartime memoirs, “If This Is a Man” and “The Truce” (first published in 1963, and renamed “The Reawakening” in the United States), and a final, searing inquiry into the life and afterlife of the concentration camp, “The Drowned and the Saved” (1986), he wrote realist fiction—a novel about a band of Jewish Second World War partisans, titled “If Not Now, When?” (1982)—and speculative fiction; also, poems, essays, newspaper articles, and a beautifully unclassifiable book, “The Periodic Table” (1975).

The publication of “The Complete Works of Primo Levi” (Liveright), in three volumes, represents a monumental and noble endeavor on the part of its publisher, its general editor, Ann Goldstein, and the many translators who have produced new versions of Levi’s work. Although his best-known work has already benefitted from fine English translation, it’s a gift to have nearly all his writing gathered together, along with work that has not before been published in English (notably, a cache of uncollected essays, written between 1949 and 1987).

Primo Levi was born in Turin, in 1919, into a liberal family, and into an assimilated, educated Jewish-Italian world. He would write, in “If This Is a Man,” that when he first learned the name of his fateful destination, “Auschwitz” meant nothing to him. He only vaguely knew about the existence of Yiddish, “on the basis of a few quotes or jokes that my father, who worked for a few years in Hungary, had picked up.” There were around fifty* thousand Italian Jews, and most of them were supporters of the Fascist government (at least until the race legislation of 1938, which announced a newly aggressive anti-Semitism); a cousin of Levi’s, Eucardio Momigliano, had been one of the founders of the Fascist Party, in 1919. Levi’s father was a member, though more out of convenience than commitment.

Levi gives ebullient life to this comfortable, sometimes eccentric world in “The Periodic Table”—a memoir, a history, an essay in elegy, and the best example of his various literary talents. What sets his writing apart from much Holocaust testimony is his relish for portraiture, the pleasure he takes in the palpability of other people, the human amplitude of his noticing. “The Periodic Table” abounds with funny sketches of Levi’s relatives, who are celebrated and gently mocked in the chapter named “Argon,” because, like the gas, they were generally inert: lazy, immobile characters given to witty conversation and idle speculation. Inert they may have been, but colorless they are not. Uncle Bramín falls in love with the goyish housemaid, declares that he will marry her, is thwarted by his parents, and, Oblomov-like, takes to his bed for the next twenty-two years. Nona Màlia, Levi’s paternal grandmother, a woman of forbidding remoteness in old age, lives in near estrangement from her family, married to a Christian doctor. Perhaps “out of fear of making the wrong choice,” Nona Màlia goes to shul and to the parish church on alternate days. Levi recalls that when he was a boy his father would take him every Sunday to visit his grandmother. The two would walk along Via Po, Levi’s father stopping to pet the cats, sniff the mushrooms, and look at the used books:

My father was l’Ingegnè, the Engineer, his pockets always bursting with books, known to all the salami makers because he checked with a slide rule the multiplication on the bill for the prosciutto. Not that he bought it with a light heart: rather superstitious than religious, he felt uneasy about breaking the rules of kashruth, but he liked prosciutto so much that, before the temptation of the shop windows, he yielded every time, sighing, cursing under his breath, and looking at me furtively, as if he feared my judgment or hoped for my complicity.

From an early age, Levi appears to have possessed many of the qualities of his later prose—meticulousness, curiosity, furious discretion, orderliness to the point of priggishness. In primary school, he was top of his class (his schoolmates cheered him on with “Primo Levi Primo!”). As a teen-ager at the Liceo D’Azeglio, Turin’s leading classical academy, he stood out for his cleverness, his smallness, and his Jewishness. He was bullied, and his health deteriorated. His English biographer Ian Thomson suggests that Levi developed a sense of himself as physically and sexually inadequate, and that his subsequent devotion to robust athletic pursuits, such as mountaineering and skiing, represented a self-improvement project. Thomson notes that, in later life, he recalled his mistreatment at school as “uniquely anti-Semitic,” and adds, “How far this impression was coloured by Levi’s eventual persecution is hard to tell.” But perhaps Thomson has it the wrong way round. Perhaps Levi’s extraordinary resilience in Auschwitz had something to do with a hardened determination not to be persecuted again.

On the basis of the first chapter of “The Periodic Table” alone, you know that you are in the hands of a true writer, someone equipped with an avaricious and indexical memory, who knows how to animate his details, stage his scenes, and ration his anecdotes. It is a book one wants to keep quoting from (true of all Levi’s work, except, curiously, his fiction). With verve and vitality, “The Periodic Table” moves through the phases of Levi’s life: his excited discovery of chemistry, as a teen-ager; classes at the University of Turin with the rigorous but not unamusing “Professor P.,” who scornfully defies the Fascist injunction to wear a black shirt by donning a “comical black bib, several inches wide,” which comes untucked every time he makes one of his brusque movements. Levi admires the “obsessively clear” chemistry textbooks that his teacher has written, “filled with his stern disdain for humanity in general,” and recalls that the only time he was ever admitted to the professor’s office he saw on the blackboard the sentence “I do not want a funeral, alive or dead.”

Throughout, there are wittily pragmatic, original descriptions of minerals, gases, and metals, as in this description of zinc: “Zinc, zinco, Zink: laundry tubs are made of it, it’s an element that doesn’t say much to the imagination, it’s gray and its salts are colorless, it’s not toxic, it doesn’t provide gaudy chromatic reactions—in other words, it’s a boring element.” Levi writes tenderly about friends and colleagues, some of whom we encounter in his other writing—Giulia Vineis, “full of human warmth, Catholic without being rigid, generous and disorderly”; Alberto Dalla Volta, who became Levi’s friend in Auschwitz and seemed uncannily immune to the poisons of camp life: “He was a man of strong goodwill, and had miraculously remained free, and his words and actions were free: he had not lowered his head, had not bowed his back. A gesture of his, a word, a laugh had liberating virtues, were a hole in the stiff fabric of the Lager. . . . I believe that no one, in that place, was more loved than he.”

The most moving chapter in “The Periodic Table” may be the one titled “Iron.” It recalls a friend, Sandro, who studied chemistry with Levi, and with whom he explored the joys of mountain climbing. Like many of the people Levi admired, Sandro is physically and morally strong; he is painted as a headstrong child of nature out of a Jack London story. Seemingly made of iron, and bound to it by ancestry (his forebears were blacksmiths), Sandro practices chemistry as a trade, without apparent reflection; on weekends, he goes off to the mountains, to ski or climb, sometimes spending the night in a hayloft.

Levi tastes “freedom” with Sandro—a freedom perhaps from thinking, the freedom of the conquering body, of being on top of the mountain, of being “master of one’s destiny.” Sandro is a powerful presence on the page; aware of this, Levi plays his absence against his presence, informing us, in a beautiful lament at the end of the chapter, that Sandro was Sandro Delmastro, that he joined the military wing of the Action Party, and that in 1944 he was captured by the Fascists. He tried to escape, and was shot in the neck by a raw fifteen-year-old recruit. The elegy closes thus:

Today I know it’s hopeless to try to clothe a man in words, make him live again on the written page, especially a man like Sandro. He was not a man to talk about, or build monuments to, he who laughed at monuments: he was all in his actions, and when those ended nothing of him remained, nothing except words, precisely.

The word becomes the monument, even as Levi disowns the building of it.

One of the most eloquent of Levi’s rhetorical gestures is the way he moves between volume and silence, appearance and disappearance, life and death. Repeatedly, Levi tolls his bell of departure: these vivid human beings existed, and then they were gone. But, above all, they existed. Sandro, in “The Periodic Table” (“nothing of him remained”); Alberto, most beloved among the camp inmates, who died on the midwinter death march from Auschwitz (“Alberto did not return, and of him no trace remains”); Elias Lindzin, the “dwarf” (“Of his life as a free man, no one knows anything”); Mordo Nahum, “the Greek,” who helped Levi survive part of the long journey back to Italy (“We parted after a friendly conversation; and after that, since the whirlwind that had convulsed that old Europe, dragging it into a wild contra dance of separations and meetings, had come to rest, I never saw my Greek master again, or heard news of him”). And the “drowned,” those who went under—“leaving no trace in anyone’s memory.” Levi rings the bell even for himself, who in some way disappeared into his tattooed number: “At a distance of thirty years, I find it difficult to reconstruct what sort of human specimen, in November of 1944, corresponded to my name, or, rather, my number: 174517.”

In the fall of 1943, Levi and his friends formed a band of anti-Fascist partisans. It was an amateurish group, poorly equipped and ill trained, and Italian Fascist soldiers captured part of his unit in the early hours of December 13th. Levi had an obviously false identity card, which he ate (“The photograph was particularly revolting”). But the action availed him little: the interrogating officer told him that if he was a partisan he would be immediately shot; if he was a Jew he would be sent to a holding camp near Carpi. Levi held out for a while, and then chose to confess his Jewishness, “in part out of weariness, in part also out of an irrational point of pride.” He was sent to a detention camp at Fòssoli, near Modena, where conditions were tolerable: there were P.O.W.s and political prisoners of different nationalities, there was mail delivery, and there was no forced labor. But in the middle of February, 1944, the S.S. took over the running of the camp and announced that all the Jews would be leaving: they were told to prepare for two weeks of travel. A train of twelve closed freight cars left on the evening of February 22nd, packed with six hundred and fifty people. Upon their arrival at Auschwitz, more than five hundred were selected for death; the others, ninety-six men and twenty-nine women, entered the Lager (Levi always preferred the German word for prison). At Auschwitz, Levi was imprisoned in a work camp that was supposed to produce a rubber called Buna, though none was actually manufactured. He spent almost a year as a prisoner, and then almost nine months returning home. “Of six hundred and fifty,” he wrote in “The Truce,” “three of us were returning.” Those are the facts, the abominable and precious facts.

There is a Talmudic commentary that argues that “Job never existed and was just a parable.” The Israeli poet and concentration-camp survivor Dan Pagis replies to this easy erasure in his poem “Homily.” Despite the obvious inequality of the theological contest, Pagis says, Job passed God’s test without even realizing it. He defeated Satan with his very silence. We might imagine, Pagis continues, that the most terrible thing about the story is that Job didn’t understand whom he had defeated, or that he had even won the battle. Not true. For then comes an extraordinary final line: “But in fact, the most terrible thing of all is that Job never existed and is just a parable.”

Pagis’s poem means: “Job did exist, because Job was in the death camps. Suffering is not the most terrible thing; worse is to have the reality of one’s suffering erased.” In just this way, Levi’s writing insists that Job existed and was not a parable. His clarity is ontological and moral: these things happened, a victim witnessed them, and they must never be erased or forgotten. There are many such facts in Levi’s books of testament. The reader is quickly introduced to the principle of scarcity, in which everything—every detail, object, and fact—becomes essential, for everything will be stolen: wire, rags, paper, bowl, a spoon, bread. The prisoners learn to hold their bowls under their chins so as not to lose the crumbs. They shorten their nails with their teeth. “Death begins with the shoes.” Infection enters through wounds in the feet, swollen by edema; ill-fitting shoes can be catastrophic. Hunger is perpetual, overwhelming, and fatal for most: “The Lager is hunger.” In their sleep, many of the prisoners lick their lips and move their jaws, dreaming of food. Reveille is brutally early, before dawn. As the prisoners trudge off to work, sadistic, infernal music accompanies them: a band of prisoners is forced to play marches and popular tunes; Levi says that the pounding of the bass drum and the clashing of the cymbals is “the voice of the Lager” and the last thing about it he will forget. And present everywhere is what he called the “useless violence” of the camp: the screaming and beatings and humiliations, the enforced nakedness, the absurdist regulatory regimen, with its sadism of paradox—the fact, say, that every prisoner needed a spoon but was not issued one and had to find it himself on the black market (when the camp was liberated, Levi writes, a huge stash of brand-new plastic spoons was discovered), or the fanatically prolonged daily roll call, which took place in all weathers, and which required militaristic precision from wraiths in rags, already half dead.

Many of these horrifying facts can be found in testimony by other witnesses. What is different about Levi’s work is bound up with his uncommon ability to tell a story. It is striking how much writing by survivors does not quite tell a story; it has often been poetic (Paul Celan, Dan Pagis, Yehiel De-Nur), or analytical, reportorial, anthropological, philosophical (Jean Améry, Germaine Tillion, Eugen Kogon, Viktor Frankl). The emphasis falls, for understandable reasons, on lament, on a liturgy of tears; or on immediate precision, on bringing concrete news, and on the attempt at comprehension. When Viktor Frankl introduces, in his book “Man’s Search for Meaning,” the subject of food in Auschwitz, he does so thus: “Because of the high degree of undernourishment which the prisoners suffered, it was natural that the desire for food was the major primitive instinct around which mental life centered.” Along with this scientific mastering of the information comes something like a wariness of narrative naïveté: such writers frequently move back and forth in time, plucking and massing details thematically, from different periods in and outside the camps. Surely, Frankl’s rhetoric calmly insists, “this material did not master me; I master it.” (This gesture can be found even in some Holocaust fiction: Jorge Semprún, who survived Buchenwald, enacts such a formal freedom from temporality in his novel “The Long Voyage”; the book is set on the train en route to the camp, but breaks forward to encompass the entire camp experience.)

Levi’s prose has a tone of similar command, and in his last book, “The Drowned and the Saved,” he became such an analyst, grouping material by theme rather than telling stories. Nor did he always tell his stories in conventional sequential fashion. But “If This Is a Man” and “The Truce” are powerful because they do not disdain story. They unfold their material, bolt by bolt. We begin “If This Is a Man” with Levi’s capture in 1943, and we end it with the camp’s liberation by the Russians, in January, 1945. Then we continue the journey in “The Truce,” as Levi finds his long, Odyssean way home. Everything is new, everything is introduction, and so the reader sees with Levi’s disbelieving eyes. He introduces thirst like this: “Will they give us something to drink? No, they line us up again, lead us to a huge square.” He first mentions the now infamous refrain “The only way out is through the chimney” thus: “What does it mean? We’ll soon learn very well what it means.” To register his discoveries, he often breaks from the past tense into a diaristic present.

The result is a kind of ethics, when the writer is constantly registering the moral (which is to say, in this case, the immoral) novelty of the details he encounters. That is why every reader who has opened “If This Is a Man” feels impelled to continue reading it, despite the horror of the material. Levi seems to join us in our incomprehension, which is both a narrative astonishment and a moral astonishment. The victims’ ignorance of the name “Auschwitz” tells us everything, actually and symbolically. For Levi, “Auschwitz” had not, until this moment, existed. It had to be invented, and it had to be introduced into his life. Evil is not the absence of the good, as theology and philosophy have sometimes maintained. It is the invention of the bad: Job existed and was not a parable. Levi registers the same astonishment when first hit by a German officer—“a profound amazement: how can one strike a man without anger?” Or when, driven by thirst, he breaks off an icicle only to have it snatched away by a guard. “Why?” Levi asks. To which comes the answer “Hier ist kein warum” (“Here there is no why”). Or when Alex the Kapo, a professional criminal who has been given limited power over other prisoners, wipes his greasy hand on Levi’s shoulder, as if the other man were not a man. Or when Levi, who was fortunate enough to be chosen to work as a chemist, in the Buna laboratory, comes face to face with his chemistry examiner, Dr. Pannwitz, who raises his eyes to glance at his victim: “That look did not pass between two men; and if I knew how to explain fully the nature of that look, exchanged as if through the glass wall of an aquarium between two beings who inhabit different worlds, I would also be able to explain the essence of the great insanity of the Third Reich.”

Levi frequently emphasized that his survival in Auschwitz owed much to his youth and strength; to the fact that he understood some German (many of those who didn’t, he observed, died in the first weeks); to his training as a chemist, which had refined his habits of curiosity and observation, and which permitted him, in the last months of his incarceration, to work indoors, in a warm laboratory, while the Polish winter did its own fatal selection of the less fortunate; and to other accidents of luck. Among these last were timing (he arrived relatively late in the progress of the war) and what seems to have been a great capacity for friendship. He describes himself, in “The Periodic Table,” as one of those people to whom others tell their stories. In a world of terminal individualism, in which every person had to fight to live, he did not let this scarred opportunism become his only mode of survival. He was wounded like everyone else, but with resources that seem, to most of his readers, unfathomable and mysterious he did not lose the ability to heal and to be healed. He helped others, and they helped him. Both “If This Is a Man” and “The Truce” contain beautiful portraits of goodness and charity, and it is not the punishers and sadists but the life-givers—the fortifiers, the endurers, the men and women who sustained Levi in his struggle to survive—who burst out of these pages. Steinlauf, who is nearly fifty, a former sergeant in the Austro-Hungarian Army and a veteran of the Great War, tells Levi, severely, that he must wash regularly and keep his shoes polished and walk upright, because the Lager is a vast machine that exists to reduce its victims to beasts, and “we must not become beasts.”

Above all, there is Lorenzo Perrone, a mason from Levi’s Piedmont area, a non-Jew, whom Levi credited with saving his life. The two met in June, 1943 (Levi was working on a bricklaying team, and Lorenzo was one of the chief masons). For the next six months, Lorenzo smuggled extra food to his fellow-Italian and, even more dangerous, helped him send letters to his family in Italy. (As a “volunteer worker” for the Reich—i.e., a slave laborer—Lorenzo had privileges beyond the dreams of any Jewish prisoner.) And as crucial as the material support was Lorenzo’s presence, which reminded Levi, “by his natural and plain manner of being good, that a just world still existed outside ours. . . . Thanks to Lorenzo, I managed not to forget that I myself was a man.”

You can feel this emphasis on moral resistance in every sentence Levi wrote: his prose is a form of keeping his boots shined and his posture proudly upright. It is a style that seems at first windowpane clear but is actually full of undulating strategies. He is acclaimed for the purity of his style and sometimes faulted for his reticence or coldness. But Levi is “cold” only in the way that the air is suddenly cold when you pull slightly away from a powerful fire. His composure is passionate lament, resistance, affirmation. Nor is he so plain. He is not afraid of rhetorical expansion, particularly when writing forms of elegy. “If This Is a Man” is shot through with sentences of tragic grandeur: “Dawn came upon us like a betrayal, as if the new sun were an ally of the men who had decided to destroy us. . . . Now, in the hour of decision, we said to each other things that are not said among the living.” He loves adjectives and adverbs: he admired Joseph Conrad, and sometimes sounds like him, except that, while Conrad can throw his modifiers around pugilistically (the heavier the words the better), Levi employs his with tidy force. The Christian doctor whom Nona Màlia married is described as “majestic, bearded, and taciturn”; Rita, a fellow-student, has “her shabby clothes, her firm gaze, her concrete sadness”; Cesare, one of those morally strong, physically vital men who sustain Levi in time of need, is “very ignorant, very innocent, and very civilized.” In Auschwitz, the drowned, those who are slipping away into death, drift in “an opaque inner solitude.”

This is a classical prose, the possession of a civilized man who never expected that his humane irony would have to battle with its moral opposite. But, once the battle is joined, Levi makes that irony into a formidable weapon. Consider these words: “fortune,” “detached study,” “charitably,” “enchantment,” “discreet and sedate,” “equanimity,” “adventure,” “university.” All of them, remarkably, are used by Levi to describe aspects of his experiences in the camp. “It was my good fortune to be deported to Auschwitz only in 1944.” This is how, with scandalous coolness, he begins “If This Is a Man,” calmly deploying the twinned resources of “fortuna” in Italian, which combines the senses of good fortune and fate. In the same preface to his first book, Levi promises a “detached study” of what befell him. The hellish marching music of the camp is described as an “enchantment” from which one must escape. In “The Drowned and the Saved,” Levi describes a moment of crisis when he knows he is about to be selected to live or die. He briefly wavers, and almost begs help from a God he does not believe in. But “equanimity prevailed,” he writes, and he resists the temptation. Equanimity!

In the same book, he includes a letter he wrote in 1960 to his German translator, in which he announces that his time in the Lager, and writing about the Lager, “was an important adventure that has profoundly modified me.” The Italian is “una importante avventura, che mi ha modificato profondamente,” which Raymond Rosenthal’s original translation, of 1988, follows; the new “Complete Works” weakens the irony by turning it into “an ordeal that changed me deeply.” For surely the power of these impeccable words, as so often in Levi, is moral. First, they register their contamination by what befell them (the “adventure,” we think, should not be called that; it must be described as an “ordeal”); and then they dryly repel that contamination (no, we will insist on calling the experience, with full ironic power, an “adventure”).

In the same spirit of calmly rebellious irony, “If This Is a Man” ends almost casually, like a conventional nineteenth-century realist novel, with cheerful news of continuity and welfare beyond its pages: “In April, at Katowice, I met Schenck and Alcalai in good health. Arthur has happily rejoined his family and Charles has returned to his profession as a teacher; we have exchanged long letters and I hope to see him again one day.” That emphasis on resistance makes its sequel, “The Truce,” not merely funny but joyous: the camps are no more, the Germans have been vanquished, and gentler life, like a moral sun, is returning. There may be nothing more moving in all of Levi’s work than a moment, early in “The Truce,” when, after the months in Auschwitz, a very sick Levi is helped down from a cart by two Russian nurses. The first Russian words he hears are “Po malu, po malu!”—“Slowly, slowly!”; or, even better in the Italian, “Adagio, adagio!” This soft charity falls like balm on the text.

Saul Bellow once said that all the great modern novelists were really attempting a definition of human nature, in order to justify the continuation of life and of their craft. This is preëminently true of Primo Levi, even if we feel, at times, that it is a project thrust upon him by fortune. In some respects, Levi’s vision is pessimistic, because he reminds us “how empty is the myth of original equality among men.” In Auschwitz, the already strong prospered—because they were physically or morally tougher than others, or because they were less sensitive, and greedier and more cynical in the will to live. (Jean Améry, who was tortured by the S.S. in Belgium, averred that even before pain we are not equal.) On the other hand, Levi is no tragic theologian. He did not believe that the “pitiless process of natural selection” that ruled in the camps confirmed man’s essential brutishness. The philosopher Berel Lang, in one of the best recent inquiries into Levi’s work, argues that this moral optimism makes him a singular figure. Lang says that Levi can be turned into neither a Hobbesian (for whom the camps would represent the ultimate state of nature) nor a modern Darwinian (who must struggle to explain pure altruism, except as camouflaged biological self-interest). For Levi, Auschwitz was exceptional, anomalous, an unnatural laboratory. “We do not believe that man is fundamentally brutal, egoistic, and stupid in his conduct once every civilized institution is taken away,” Levi writes forthrightly. “We believe, rather, that the only conclusion to be drawn is that in the face of driving need and physical privation many habits and social instincts are reduced to silence.”

In normal existence, Levi argues, there is a “third way” between winning and losing, between altruism and atrocity, between being saved and being drowned, and this third way is in fact the rule. But in the camp there was no third way. It is this apprehension that expands Levi’s understanding for those caught in what he called the gray zone. He places in the gray zone all those who were morally compromised by some degree of collaboration with the Germans—from the lowliest (those prisoners who got a little extra food by performing menial jobs like sweeping or being night watchmen) through the more ambiguous (the Kapos, often thuggish enforcers and guards who were themselves also prisoners) to the utterly tragic (the Sonderkommandos, Jews employed for a few months to run the gas chambers and crematoria, until they themselves were killed). The gray zone, which might be mistaken for the third way, is an aberration, a state of desperate limitation produced by the absence of a third way. Unlike Hannah Arendt, who judged Jewish collaboration with infamous disdain, Levi makes a notable attempt at comprehension and tempered judgment. He finds such people pitiable as well as culpable, because they were at once grotesquely innocent and guilty. And he does not exempt himself from this moral mottling: on the one hand, he firmly asserts his innocence, but, on the other, he feels guilty to have survived.

Levi sometimes said that he felt a larger shame—shame at being a human being, since human beings invented the world of the concentration camp. But if this is a theory of general shame it is not a theory of original sin. One of the happiest qualities of Levi’s writing is its freedom from religious temptation. He did not like the darkness of Kafka’s vision, and, in a remarkable sentence of dismissal, gets to the heart of a certain theological malaise in Kafka: “He fears punishment, and at the same time desires it . . . a sickness within Kafka himself.” Goodness, for Levi, was palpable and comprehensible, but evil was palpable and incomprehensible. That was the healthiness within himself.

On the morning of April 11, 1987, this healthily humane man, age sixty-seven, walked out of his fourth-floor apartment and either fell or threw himself over the bannister of the building’s staircase. The act, if suicide, appeared to undo the suture of his survival. Some people were outraged; others refused to see it as suicide. The implication, not quite spoken, was uncomfortably close to dismay that the Nazis had won after all. “Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later,” Elie Wiesel said. Yet Levi was a survivor who committed suicide, not a suicide who failed to survive. He himself had seemed to argue against such morbidity, in his chapter on Jean Améry in “The Drowned and the Saved.” Améry, who killed himself at the age of sixty-five, said that in Auschwitz he thought a great deal about dying; rather tartly, Levi replied that in the camp he was too busy for such perturbation. “The business of living is the best defense against death, and not only in the camps.”

Many contemporary commentators knew little or nothing about Levi’s depression, which he struggled with for decades, and which had become desperately severe. In his last months, he felt unable to write, was in poor health, was worried about his mother’s decline. In February, he told his American translator Ruth Feldman that his depression was, in certain respects, “worse than Auschwitz, because I’m no longer young and I have scant resilience.” His family was in no doubt. “No! He’s done what he’d always said he’d do,” his wife wailed, when she heard what had happened. In this regard, one could see Levi as a survivor twice over, first of the camps and then of depression. He survived for a very long time, and then chose not to survive, the terminal act perhaps not at odds with survival but continuous with it: a decision to leave the prison on his own terms, in his own time. His friend Edith Bruck, herself a survivor of Auschwitz and Dachau, said, “There are no howls in Primo’s writing—all emotion is controlled—but Primo gave such a howl of freedom at his death.” This is moving, certainly, and perhaps true. Thus one consoles oneself, and consolation is necessary: like much suicide, Levi’s death is only a silent howl, because it voids its own echo. It is natural to be bewildered, and it is important not to moralize. For, above all, Job existed and was not a parable. ♦

*An earlier version of this article misstated the number of Jews in Italy during the pre-war era.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

The response to my attack on Western birthdays, Christmas presents, child-rearing and consumerism — “Photo: Athens metro — ‘Today is the nameday of…’“ — was terrible and swift. All were from people infuriated, offended, mostly women (just stating a fact), and totally, entertainingly point-missing. “What’s wrong with buying a present for a friend you appreciate and care for?” “That was a bitter and mean post.” “A birthday cake is a way to show a child you love him.” And, no, I “obviously” don’t have children. (Christmas and children, especially — since both were invented at the same time in the nineteenth-century — are a particularly pointed way to épater le bourgeois when you need to.) People felt demeaned, ridiculed.

I felt bad.

And that made me think about it some. And I said to myself: “Wait a second; P. and I didn’t have a $100,000 wedding; nobody ever got me a house-warming gift off a Crate & Barrel registry, neither when I inherited my father’s house or bought my new place; I’m not getting pregnant any time soon…” And I began to see the logic behind Western-style asking for presents. Specific ones. I started to see the wisdom of white-folk…

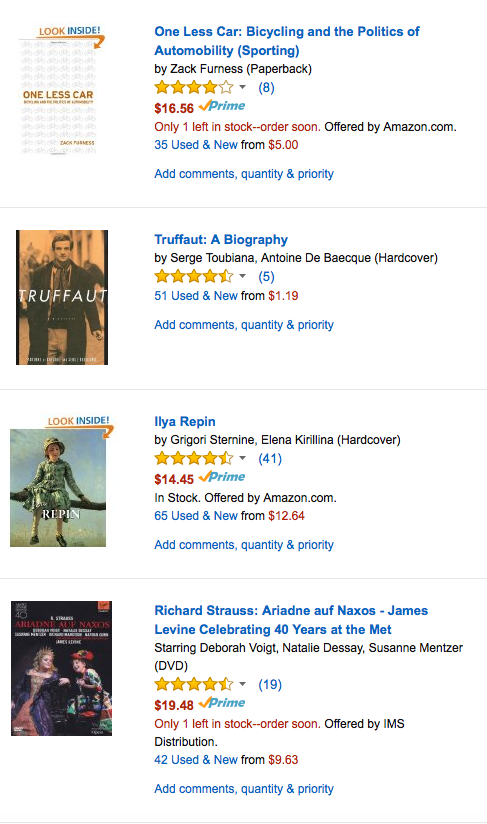

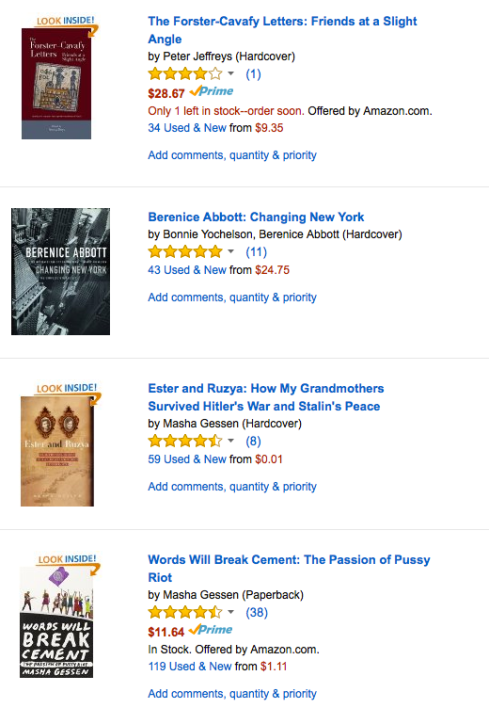

And so I’m sending out my Amazon wish-list as my nameday registry. I’ve pasted a few screenshots below of the stuff that I’d really like, but I’m also sending out the link to the whole list so that you have a greater variety of gift-giving options. My nameday was yesterday December 6th, but you traditionally have 40 days to wish me well, so let’s say that goes for buying me a gift too. If we take into consideration that Old Julian Calendar St. Nicholas isn’t till December 19th, then you have way into January to get me something.

Thanks in advance and hugs and kisses to all.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

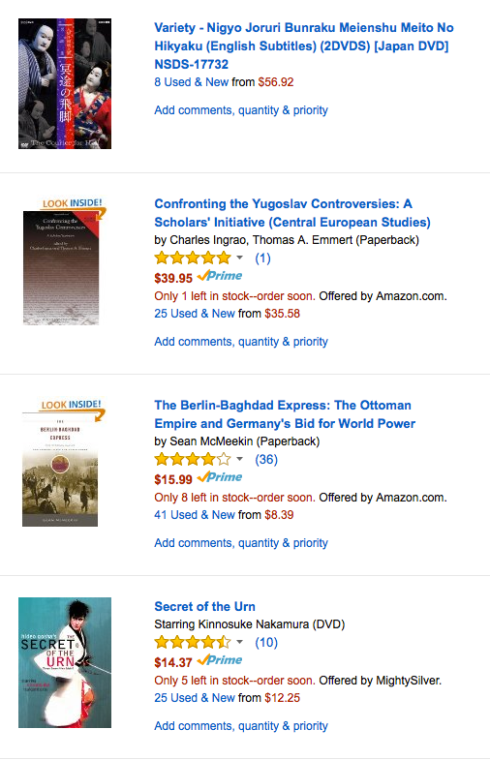

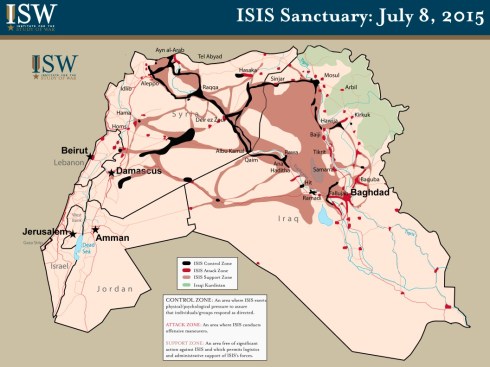

I’m going to have to write this post in bullet points of varying length, that I guess reflect the tragic fragmentation of my subject matter in some way, because putting it all together into a coherent “opinion piece” is as hard as finding coherent policy to deal with the problem itself has been. I was against talking about Syria in the beginning of its crisis as if it were an inherently fragmented and “artificial” colonial creation, as it had become the fashion to speak of most of the Levant at some point or another. I particularly objected to Andrew Sullivan’s obnoxious “Syria [or Iraq] is not a country” declarations. But since then, that’s become the reality – an insistent enough discourse makes itself a reality — so it seems to be more useful to take on all the regions, factors and players involved one at a time…and if I can bring them together usefully at the end, I will.

Russia and Assad: It’s obvious that Russia is pursuing its own agenda in Syria, but frankly — isn’t everyone? — so that’s no great cogent or original observation, and to be very frank, shouldn’t play into our response to either Assad or Putin, given the point to which things have reached at this point, because the degree to which you or I can stomach either Assad or Putin is not the point. The point is that right now I can see no great tragedy in an Assad-run — for how long can be decided later, with Russia (see below) — Russian semi-protectorate that would run from the Latakya Alawite coast down the Hama-Homs-Damascus-Dar’a, corridor, that would provide security and stability for even the region’s originally anti-Assad Sunni population, and even attract Sunnis from the rest of the country who could make their way there: such – I would think – is the ethical questionability of the various Sunni groups (aside from just ISIS I mean) into whose hands the original uprising has fallen and the degree of their war-weary victims’ terror; and — because I think it’s important to declare your subjective affinities before you can honestly put forth your hopefully objective suggestions or propositions – I hope such an entity would also provide a safe haven for part of what’s left of Syrian Christianity as well. (Yes, MESA girls, you’ve caught me again.) It would also be a good idea if we learned a little bit about the Assads and the Alawite past in the region (as it would be equally good for us to know something of Turkish/Kurdish Alevis as well), not to exonerate Assad for anything, but so that we know what we’re talking about before we start unproductively babbling about villains just sprouted out of the earth – like we did in Lebanon in the past about the Gemayels and Maronites or the Jumblatts and Druzes or southern Shiites and Hezbollah. This is homework one would like to assign to the Levant and the Middle East’s Sunni majority as well: a request that it examine its moral conscience, if such a thing exists, and its treatment of minorities in the past, but I understand that that’s probably a tall order that we can’t wait for them to comply with in order to bring some relief to the current hellishness. Assad remaining on as President of at least part of Syria is an ugly proposition. But more resistance is a luxury for Western intellectuals at this point.

So let Russia go for what it wants for now; it’s in most everyone’s interest and let’s try to turn it to everyone’s advantage instead of attacking her for every move she makes. ENGAGE RUSSIA. I beg everyone. A plea I will make later as well and repeatedly.

The Shiite crescent or triangle: This is the very real alliance of Bashar al-Assad, Hezbollah in Lebanon, a largely Shiite entity that’s essentially what’s left of Iraq, and Iran. It’s not a product of Israel’s paranoid imagination, but only Israel thinks it has any real reason to be worried about it and therefore Israel should be promptly ignored on every point and aspect of those worries.

Bashar al-Assad

Neither Iraq nor the Iraqi army are functioning entities, so we can temporarily remove them from our discussion. I think I’ve addressed the moral “problematicness” of Assad: that there can be no solution in Syria till he’s gone, though, is a moralistic pose and not a truly moral position — sadly, one even Obama is fond of striking — and is an excuse for doing nothing and a recipe for letting the current holocaust continue. As for Hezbollah: whatever we think of its origins or the nature of its religiosity or its political ideology, it’s a highly professional organization with a highly professional, well-trained and hardened army, and the only Arab or other force that has put Israel in its place twice – took a little longer the first time but was pretty snap the second – and has pretty much served as an Akritai line that has kept it there since and, whatever its political tactics are (I honestly can’t say), it seems to me to be the one force that has kept Lebanon relatively stable (yes, as had Syria) for the past twenty years or so.

Of course, it does this with the massive organizational and material help of Iran. Which brings us to…

Iran: Get over Iran. It became a comforting cliché, with which the Middle Eastern Studies academic left aunanized itself for several decades: that the imperialist West had aborted every modern attempt at a democratic, civil society in the Muslim world and that that was therefore responsible for the rise of political Islam. Tell me which countries we’re talking about and who the leaders were who were going to lead them to this heavenly, secular modernity? The even more militaristic and fascist and statist successors of Kemal in Turkey? Look how that’s turning out and it’s still incomparably the best of the batch and, ok, there’s still hope recent setbacks can be reversed. Who else? Nasser and Egypt? Arafat or current Palestinian leadership? The Ba’athist successors of the Hashemites in Iraq? Maybe in Jordan? Ben Bella and Algeria? Bourguiba even and Tunisia? The Saudis? Jinnah’s successors, further east, or even Jinnah himself? Maybe the Afghan royal family? Who?

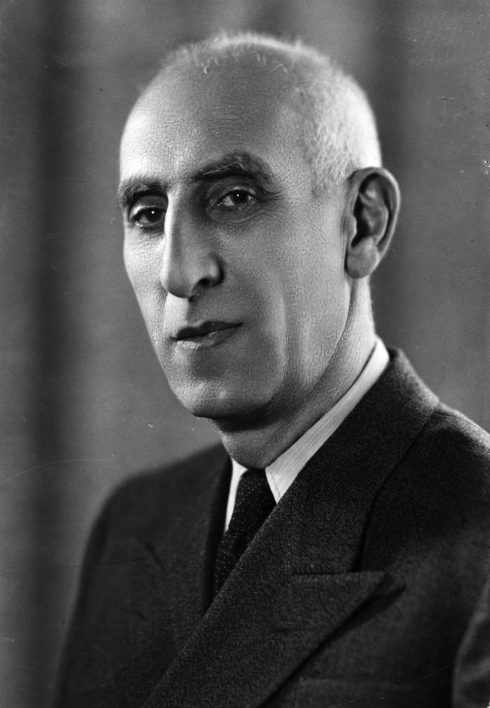

The only country in the Muslim world that in my humble opinion seemed to have had many of the prerequisites for a secular, civil society, perhaps a constitutional, truly assembly-based government, and a leader with an appropriately intellectual, bourgeois background and education — and accompanying democratic inclinations — was Iran and Mohammad Mosaddegh. And the Anglo-Americans destroyed that experiment. And yet Iran still seems to be the country, which despite the powerful institutional obstacles, has, on a popular level at least, the temperamental prodiagrafes for the development of such society and is poll-wise the most pro-American in the region. What is the rationale behind continuing to villainize and sanction and isolate? Ok, maybe not “what is the rationale?” But I’m simply calling for the acceptance of the fact that allowing Iran to open up to the world would inevitably – no, don’t give me Russia or China as examples – lead to an internal opening up as well, and both Iranians and the rest of the world have only to gain, when, and not if, that happens. Let it happen faster. As fast as you can.

Mohammad Mosaddegh