…or, how does one react to the tiring self-righteousness of certain left-dudes.

X. (I want to respect anonymity) is a journalist who I generally like personally, whose work I respect, and whose opinions and judgements about the Middle East I value and find extremely useful; he’s my go-to guy, especially about Lebanon, a country I find particularly fascinating. But he’s called me a few times too many on what are supposedly my biases, which generally consist — sorry to be crude — of my not being “brown enough”, in a way I find not just a little offensive.

I call it “not-brown-enough” because though his criticisms seem to indicate that he believes I’m on the right side where the oppressed are concerned, he also seems to think that I’m not on the side of those he considers the really and truly oppressed.

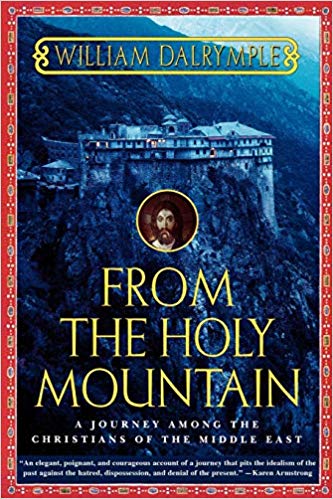

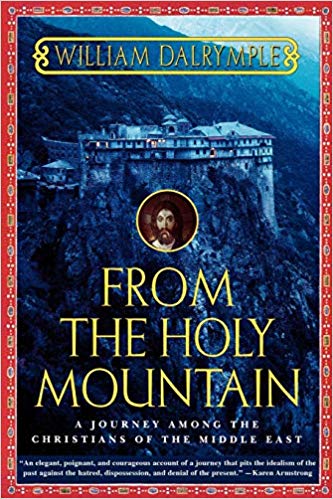

For one, he’s patently impatient and irritated by my concern for Middle Eastern Christians — though that’s par for the course when dealing with post-Christian Western intellectuals who, at best, have only traumatic memories of growing up Catholic or Lutheran and see any defense of Christianity as a racist and irrelevant leftover piece of creepy reaction. So for X., someone worrying about the survival of Eastern Christianity seems to be tantamount to being Pat Robertson. For my part, I don’t think that, being Greek Orthodox, I should have to apologize for caring about the losing battle that eastern Mediterranean Christians are fighting. (I would take a guess and assume X.’s unspoken attitude basically consists of: “Oh, so many millions are truly suffering and displaced and dying and you’re worried about 60 old Greek ladies in Istanbul”; well, yeah, somebody has to worry about those old Greek ladies in Istanbul too, ok? No apology). Nor do I think that I should have to apologize for believing that that battle for survival is real — or apologize for believing that it’s an ancient battle that dates back to the glorious entry of Arabs and Islam into the Greco-Roman-Christian and Sasanian worlds — or apologize for believing that that “entry” was anything but an unalloyed good — or apologize for believing that sectarianism in the region has a long and bloody history way before any blood-letting was caused or provoked by Western colonial powers. I should probably send him a copy of one of Walter Dalrymple’s early and brilliant books: “From the Holy Mountain: A Journey among the Christians of the Middle East“.

But in an exchange about this issue, he had the gall to refer once to what he calls “elite minority supremacism”. Remember that phrase; it’ll come back to haunt us all. This means that it’s racist, on some level, and politically incorrect of me, to care about the rights of minorities — Orthodox Christians, Maronites, Jews, Copts, Armenians, the Alawites of Syria, the Shiites of southern Lebanon and the Bekka — when it’s really the Sunni majority of the Levant and Iraq that are the true victims.

Sorry. The Sunni Muslim majority of the region were the politically, socially and economically privileged majority group until the late nineteenth century and specifically 1918 — that tragic year when Turkey capitulated and the Ummah and Caliphate were humiliated by the boot of the kaffir West. That tragic humiliation is what left us with the likes of Sayyid Qutb and Osama bin Laden and Mohamed Atta, all so enraged and humiliated and boiling over with rancid testosterone.

Granted, not much sympathy from me there. And the fact that the non-Sunni or non-Muslim minorities of the region might have found that “humiliation” to have been a liberation of sorts, after centuries of discrimination by said Sunnis, seems perfectly natural to me. There’s a reason Maronites and Syrian Christians turned to France in the mid-nineteenth century and especially after 1860. There’s a reason Syrian Alawites became the French Mandate’s mercenary force. There’s a reason Serbs looked — somewhat ambiguously, with their typical wariness and sense that they don’t really need or think they should trust anybody else’s help — to Austria, and that Bulgarians and Armenians looked to an Orthodox Russia for most of the last two centuries of Ottoman rule in the Balkans and Anatolia. They took a route that they believed, rightly or not, would give them protection from the ethnic and religious groups that had systematically marginalized and persecuted them. So the result is that the 20th century and modernity come around and Syrian Alawites become the dominant military and therefore political force in that country. The 20th century and modernity come around and most Maronites and other Christians in Lebanon are generally better educated, more connected to the outside world and better-off economically than most Lebanese Muslims. And there’s a whole set of reasons that the 20th century came around and Ottoman Greeks, Armenians and Jews were also generally better educated, more connected to the outside world and better-off economically than most Ottoman Muslims except for a small elite. Is the colonizing West entirely to blame for that too?

What fantasy world do intellectuals and journalists like X. live in, where everyone in the Near East loved each other and lived in harmony until the evil West and its divide-and-conquer policies showed up? I would love to believe that but it’s just not supported by the historical record. It’s a common academic trope of intellectuals from the region because it jibes with leftist anti-colonial discourse and it absolves regional players of any responsibility. (See Ussama Makdisi‘s Aeon article “Cosmopolitan Ottomans: European colonisation put an abrupt end to political experiments towards a more equal, diverse and ecumenical Arab world” or “Ottoman Cosmopolitanism and the Myth of the Sectarian Middle East“, or any of his other work for classic examples of this fictional genre; it’s his forte; he’s made a career of the argument.)

“European colonisation put an abrupt end to political experiments towards a more equal, diverse and ecumenical Arab world”

“European colonisation put an abrupt end to political experiments towards a more equal, diverse and ecumenical Arab world”

And wait a minute; let’s backtrack: you discriminate against a minority group; you bar it from conventional access to power and wealth; you confine it to the interstices and margins of your society, and in those interstitial niches they develop the skills and the talent that enable them to survive, and not only to survive, but to come out on top once they’re emancipated — and then that only makes you hate them even more — I’m sorry, but is that not the fucking textbook definition of anti-semitism??!! Call it “elite minority supremacism” if you like. It’s the same thing. And just as nasty, racist and toxic.

Then there was a persnickety exchange about minorities — again — in Turkey this time. X. disagreed with an eccentric but actually quite informed and smart Byzantinist Brit on Twitter, because he tweeted that “the state of minorities in Turkey is not a good advertisement for dhimmitude”. “Dhimmi” in Arabic, or “Zimmi” in Turkish and Farsi pronunciation, is a term that specifically — and very specifically — means the non-Muslim subjects of an Islamic state. X. thought that it was “epistemologically sloppy” of him to refer to the now practically vanished Christian and Jewish minorities of Turkey and ignore the intra-Muslim (for lack of a better word) minorities, like Kurds, Alevis, Zaza-speakers, or the Arabs of the south-east and Antakya (X. calls it Hatay, but I refuse to use the place-names of Turkish science-fiction nationalism). Again, the Byzantinist Brit was supposedly being biased because he lamented the fate of Turkey’s non-Muslims and ignored its persecuted and more deserving of pity Muslim “minorities”. But that’s his right to do and feel — and mine. And, in fact, there was absolutely nothing “epistemologically sloppy” about his analysis. By simple virtue of the fact that he used the word “dhimmi”, he made it unequivocally clear that he’s talking about Turkey’s non-Muslim minorities; he’s not using a “dog-whistle to mean Christians,” as X accused him of in one tweet. He’s stating it very loud and clear that that’s what he’s concerned with. But for X. that makes him biased and probably an Islamophobe, while all that he — and I — were doing was simply pointing out the fact that there was/is a qualitative and taxonomical difference between the status of non-Muslims in Turkey and sub-groups within the Muslim majority in Turkey. And proof of that qualitative difference is born out precisely by the fact that the Christian and Jewish groups have practically vanished; “elite minority supremacism” apparently didn’t save them. Tell me what X.’s objection was, because I can’t make heads or tails of it — talking about “epistemologically sloppy”.

Then we go to New York. I post this piece: “The insufferable entitledness of bikers“ :

“The National Transportation Safety Board has recommended that helmets be required for all bicyclists in the U.S., but some advocacy groups say putting the recommendation into law can have unintended consequences.”

[Me]: How ’bout we let them crack their heads open, and then maybe they’ll think about how biking — in a city like New York at least, not Copenhagen — is a deeply ANTI-URBAN, elitist, yuppy phenomenon that makes our cities’ centers more and more inaccessible to borough dwellers who can’t afford to live there, to street vendors, to truckers, to commercial traffic, to theater-goers and to everything that makes New York New York and not Bruges, all dressed up in the pedantic Uber-Green self-righteousness of a bunch of rich vegan kids from Michigan?

–

Walt Whitman would be turning in his grave.

–

Blows me away that more people don’t see that.

–

I immediately get a response from X., because he’s one of those people who always has a pre-printed ravasaki in his breastpocket with an analysis and a supporting, supposedly proof/text for almost any political issue. You’re concerned with Christians in Syria? X. is right there on the barricades to call you an elite minority supremacist. You suggest there seems to have been a shortage in the Arab world of leaders able to successfully create a solid civil society and functioning democracy, X. immediately has a long list of names for you, even if that list includes more than a few murderous dictators. You wonder what suddenly caused Syrian Sunnis to stand up to the despicable Assad regime, X. tells you part of the issue is agriculture and water supply. You accept the fact that environmental conditions might have been what literally and figuratively sparked the civil war, and then X. tells you water and drought have nothing to do with it. You articulate an opinion on the mating habits of homosexual penguins in Antarctica and…well, you get the point.

–

Hey, maybe that’s what makes a good journalist, but it also leads to dizzying instant analyses and superficial opinions, without a single “well…” or “maybe…” or “Shit…I never thought of that” or any even remotely multi-facetted take on things. Sorry to be channeling Sarah Palin — never thought it would come to this — but so many exchanges with X. immediately degenerate into “gotcha” discourse.

–

So, he responds, with lightning speed:

Actually most bicyclists are low-income immigrants. Which is why upscale white people love to shit on them.

–

Not everyone can afford first-world privileges like taking taxis. Even riding public transportation is too expensive for a lot of folks.

With an informative link attached:

Except, I don’t know any upscale white people who shit on bikers. As far as New York is concerned, I don’t have statistics, but my visual gut observation is not that there are multitudes of immigrants riding bikes around, but almost exclusively young white guys — the “upscale white people” who supposedly shit on bikers. ?

–

And here I think it’s important to point out that it’s a bit disingenuous of X. — if not just a total misrepresentation of facts — or maybe even a teeny-weeny bit of what we used to call lying — to send this particular article because it refers almost exclusively to Houston and totally exclusively to Sun-belt cities and southern California: all cities that are of radically lower density than New York, which is the city the discussion was about, and that, incidentally, have kinder weather. Bikes there may not cause a problem or may be mostly for lower-income city-dwellers. But in New York they’re a nuisance. And I see and know very few poor people using them.

–

I wrote back:

–

“Very possibly low-income immigrants, ok, but do we have and how exactly do we get statistics about that? [As it turns out we don’t; we only have statistics from Houston] But even if that’s true, they don’t demand that a modern, industrial city, built and designed to be a modern, industrial city, change itself and cater to a mode of transportation that such a high-density city [like New York and unlike Houston] is not designed to accommodate.

–

“And as for taking taxis, or even the subway, I am and have always been a borough-boy, who couldn’t and can’t afford to take a taxi to get into Manhattan, nor could I tolerate a commute to and from a two-fare zone, which is what we used to call neighborhoods where you had to ride the subway line to the end and then pay a second fare to take a bus, like Whitestone, where I spent my teens and twenties. I used to drive into Manhattan (20 minutes instead of 2 hours on public transport) and parking was easy to find even on a Saturday night in the East Village. And while we’re on the subject of poor immigrants, have you asked a Sikh cab-driver how he feels about the pedestrianization of Times or Herald or Madison or Union Squares? Or — while we’re weeping for the working class — have you asked a truck driver who has to negotiate backing his truck up into Macy’s loading platform with Herald Square blocked off and 35th street narrowed by a biking lane how he feels about that?

–

A superfluous number of pedestrianized zones, biking lanes, Citibank bike stops, farmers’ markets, happy piazzas for office workers to eat their $15 prosciutto sandwiches from Eataly, Bloomberg’s unsuccessful plan to put tolls on East River bridges — a flagrant fucking attempt to keep the non-rich out of Manhattan — because his constituency wanted less traffic and less noise in their neighborhoods, have all contributed to making Manhattan less accessible for me, because I, like your immigrants, can’t afford to live there.

–

“And even if there are more Mexicans delivering Chinese food on their bikes than there are entitled pricks from Indiana using bicycles, the Mexicans don’t give me attitude about how I’m not respecting their hobby. They’re too busy working. Plus it’s hard for me to imagine that taking care, storing, maintaining and protecting your bike from theft or vandalism in New York is cheaper than taking the train.

–

“You know that long passage between the E train at 42nd Street that connects to the 7 train? Would you, at rush hour, let a toddler free there? Obviously not. Because you wouldn’t let a being of radically different size and speed go free in a space where he’s more likely than not to get trampled.

–

“Nor could you possibly ask NYers rushing to work to watch out for that toddler.”

–

Again, I’m progressive but not quite progressive enough for X. Poor, brown immigrants should be entitled to ride their bikes anywhere at any time, though that’s a sociological type that barely exists in New York. But a white, working-class, ethnic-American kid from outer Queens like me can go fuck himself (the implication that I was ever rich enough to take a cab into the city on a regular basis is infuriating) and I can be denied access to the pleasures and resources of Manhattan, even as Manhattan becomes a sterile playground for the rich on one end and and hip enough to let hipsters and X.’s poor immigrants ride their bikes supposedly on the other end. No room for me, who falls in the middle of that spectrum.

–

Density, up-close, claustrophobic even; maddening; density is the essence of a city like New York. If you’re from there you know that; if you’re not, it might make you a little nuts and you might long for parks and greenery and bike-lanes. And it’s almost always non-New-Yorkers who are clamoring for these pleasantries that will remind them of Madison, WI. Density; it means cars and street traffic too — and noise — things that give access to the maximum amount of people, cities you can get to easily and that let you in. Not obnoxious, exclusive enclaves like Georgetown or Cambridge, MA, where you need to prove you’re a resident to even park on one of its streets. Look at what pedestrianization has done to Istanbul, where Erdoğan has transformed Taksim, Tâlimhane and the upper Cumhurriyet into a concrete wasteland with all the charm of a Soviet plaza in a city like, let’s say, Perm’.

–

City of the sea! city of hurried and glittering tides!

City whose gleeful tides continually rush or recede,

whirling in and out, with eddies and foam!

City of wharves and stores! city of tall façades of mar-

ble and iron!

Proud and passionate city! mettlesome, mad, extrava-

gant city!

“Mettlesome, mad, extravagant…”

More later — maybe. This gets exhausting.

Mulberry street, c. 1900 — “Density, up-close, claustrophobic even; maddening; density is the essence of a city like New York.”

Mulberry street, c. 1900 — “Density, up-close, claustrophobic even; maddening; density is the essence of a city like New York.”

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

Tags: "Cosmopolitan Ottomans", "elite minority supremacism", "From the Holy Mountain: A Journey among the Christians of the Middle East", "Mettlesome, "Mettlesome mad extravagant...", "Ottoman Cosmopolitanism", "The insufferable entitledness of bikers", 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war, 1918, Aeon, Alawites, Alevis, Anatolia, anti-semitism, Antioch, Arabic, Arabs of Antakya, Armenians, Austrians, Ç, Balkans, Bekka valley, bikers, Bloomberg, Bruges, Bulgaria, Bulgarians, Byzantinists, Caliphate, Cambridge MA, Christian and Jewish minorities of Turkey, Citibank bike stops, Copenhagen, Copts, Cumhurriyet, dhimmi, East Village, eastern Mediterranean Christians, Eataly, Erdogan, extravagant...", farmers' markets, Farsi, Georgetown, Greek Orthodox, Hatay, Herald Square, Houston, Islamophobe, Αντιόχεια, Jews, Kurds, Lebanon, mad, Madison Square, Maronites, MESA, MESA dudes, Mexicans, middle east, Middle Eastern Christians, Minorities in Turkey, Mohamed Atta, New York, Orthodox, Osama bin Laden, Perm', rich Vegan kids from Michigan, Russia, Sarah Palin, Sayyid Qutb, Serbia, Serbs, Sikh cab-driver, Sun-belt cities, Syrian Christians, Taksim, Tâlimhane, The National Transportation Safety Board, Times Square, Turkey, Turks, Ummah, Union Square, urban density, urban density of New York, Ussama Makdisi, Walt Whitman, Walter Dalrymple, Whitestone, Wokers, yuppies, Zaza-speakers, zimmi

“European colonisation put an abrupt end to political experiments towards a more equal, diverse and ecumenical Arab world”

“European colonisation put an abrupt end to political experiments towards a more equal, diverse and ecumenical Arab world” Mulberry street, c. 1900 — “Density, up-close, claustrophobic even; maddening; density is the essence of a city like New York.”

Mulberry street, c. 1900 — “Density, up-close, claustrophobic even; maddening; density is the essence of a city like New York.”

Sorry. Kind of a moral mission on my part: can’t let celebration of cosmopolitan, tolerant Islam (or any monotheism) get away with exaggerations.

A tableau/scene — the still, fabulous compositions of Paradzhanov’s style, that make so much of his work “our parts” pornography, in essence — from Color of Pomegranates:

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–