Queensborough Bridge (photo: Matt Lawson)

I don’t often get the chance to aimlessly stroll around the City much anymore – I mean Manhattan, not that City – but especially in the summertime, when New York is hot like it is today but not unbearably so, so many of it’s sensory delights, especially its human ones, are on display everywhere that if I get the chance, I can’t stop walking, eating, drinking things, and checking people out — the perfect tourist in my own city.

My shrink was unusually cute today and I had a really good time with him and that only added to my kefia and energy. I walk straight down 5th to St. Patrick’s to give my saludos to St. Anthony, since he’s my most best beloved in the Catholic pantheon, and then turn off 5th to Madison because I can’t deal with any tourists but myself, though I’ve been finding European tourists to be significantly less obnoxious recently – and significantly less, generally — now that they don’t have any money either.

I know where I’m going anyway – at least for starts. I’m making a bee-line for faloodeh. Don’t ask me wtf… I must have been dreaming about it last night and sleep-walking (which I did a lot of as a kid) when I posted that piece about faloodeh: “This is what I want in this heat: Faloodeh”, because it was posted at 7:00 a.m., which is the middle of the night for me, and when I got up at my usual time I didn’t even remember having put it up. But I have faloodeh on the brain right now, man, and am heading straight for the only place in New York where I know I can get it, an Iranian restaurant on 30th St. called Ravagh.

It’s better than the fantasy had been, which usually can’t be said about almost anything in life. Look at it; it even looks beautiful. It’s got that perfect color palette that everything Persian does, always pushing the limits of saturation but never becoming gaudy or tacky.

Faloodeh (click)

Ravagh is a pretty good place, at least in the opinion of this non-Iranian. The appetizers are nothing to get hopped up about, but the kebabs are great, as are the khoresh and the great pomegranate and walnut fesenjun, but I’m also a sucker for any food with fruit and nuts in it, not only taste-wise but ‘cause I’m also historically stimulated by it. In Persian food we find tastes and combinations that have, certainly, disappeared from Greek tastes (?) (a Neo-Greek can vomit if he finds so much as one raisin in his dolma) but from increasingly flattened and simplified Turkish tastes too. Iranians, however, are still geniuses, as I said in my trance this morning, at subtle sweet-and-sour combos, at using spices without having to overwhelm you with an indigestible quantity of onion-garlic-ginger canvass on which to use them, like a lot of Indian food does, and for appreciating the taste and aroma of every herb and green thing that this earth can give us.

(It’s also the work-place of one of the most attentive waitresses and the most beautiful Uzbek woman in the world; no exaggeration, this is one of the most gorgeous women in New York, the female equivalent of one of Hafez’ dangerously beautiful young Turkish men: “Zabaan-e-yaar-e-man torki wa man torki nami daanam,” “The language of my friend is Turkish, but I know no Turkish.” Ok, that’s not Hafez; it’s Amir Khusrau, but I can’t think of any Hafez right now…)

I head downtown after that to the East Village to see my favorite Hanuman in the city. Midtown’s blank Wasps, smart-looking Jewish guys and buff borough boys in tight dress shirts and ties start giving way to sweet, ethnically unidentifiable guys with lots of tattoos and scrawny beards. I pass Mono on the way and see its beautiful, sweaty ham sitting in the window and think: ok, maybe later.

I’m irritated again my Daddy Bloomberg’s traffic lights that tell you how many seconds you have to get across a street before you’re flattened by a flock of taxi cabs.

I see New Yorkers running, frantic, across the street; New Yorkers, as long as I’ve known them, waited till they formed a critical mass on any street corner and simply marched together into the middle of the street, stopping traffic at will. Now he’s got us running. I wish again he would just go back to Boston. It’s already the city that he wants to turn New York into; why is he bothering with us? They’ll love him there. Give him a fourth and even fifth term, make him Czar of Massachusetts Bay colony. Just go. Go away.

“They save lives!” Ok. I don’t know if they do. But even if they do, a civilization where the saving of life is of consistent and constant greater concern than its quality, where not only do lives need to be saved but all risk — germs in bathrooms, kids getting their knees scuffed — needs to be legislated out of them, a world where, as James Hillman put it: “quantity of life is at all costs more important than quality…” is a civilization we’re not going to be very happy to have lived so long to see.

Anyway, I adore this particular Hanuman that I’m on the way to see because it’s a gigantic brass murti and he’s in his kneeling pose, which I love, because it shows off his big thighs and his great forearms holding his mace over his shoulder and the huge chest he has to have to hold that heart so enormous that God himself and everyone He loves can fit into it. They never dress him there either, because it’s a difficult pose to dress, so whenever you go he’s always there gleaming in all his bare muscled glory, ready to go to war for Ram and his Kingdom, or for anyone who loves Ramji the way he does.

The problem is that this temple is in the East Village and its whole community is white people, which means it’s really not a Hindu temple or mandir at all but an East Village center for non-stop yoga classes or kundalini workshops, so you’re almost never allowed in for a little bit of darshan and peace and quiet with your god. I’ve tried to suggest in the past that maybe there should be some more “open” time for someone like me. But you can’t complain there either because these white “Hindus” have gotten modern Hinduism so frighteningly mixed up in their heads with Buddhism and any other New Age stuff they think they believe in, that if you complain and look even remotely irritated, they look at you sadly like you’re accumulating bad karma and they have no way of helping you. On top of that, there’s only flower offerings permitted, because – I swear – laddoo and peda and other mithai have “lots of refined sugar and saturated fat” in them, so you can’t even walk away from aarti there (yes, they have aarti every evening at least) with a good piece of prasad and its gratifying sweetness in your mouth. I really want to ask these people what it is they’re saving their bodies for sometimes; they ever heard of that whole dust to dust bit?

Again, I don’t get to see my Hanuman.

This is the pose of Hanumanji I love most, a little one at a Jackson Heights shop. Now imagine him nine feet tall and all gleaming brass, like he is at that temple. (click)

I remember the ham at Mono though.

Casa Mono is the restaurant really; it’s part of the Batalli empire but it’s actually a very intimate place with hands down the best Spanish food in New York, and I think as good as anything I’ve ever had in Spain as well. I always wait, no matter how long it takes, for a seat at the bar by the open kitchen because you get to see the mens’ performance there and it’s good to see men sweat and handle knives and fire and and meat and heat (the night there’s a woman behind there I won’t return, I swear; I’ll just suffer without Mono for the rest of my life**). You also get to watch the growing status, knowledge and confidence of New York’s Mexican workers there too, their steady rise to the top, the same trajectory we followed decades before, and the way that — not only Mexican hard work — but Mexican wit and playfulness, which almost everyone now understands some of, have become the esprit de corps glue that holds together so many excellent New York restaurants like this one. There’s often a Mexican or Ecuadorian trainee behind the counter, and a guy who I think is the line’s number two, a sexy tatooed-up Ed Norton look-alike that I really love. But if you’re especially lucky you’ll get to see head chef Anthony Sasso back there cooking, a guy with a body that looks like he used to be an Olympic diver, who never sweats, and who cooks with such ease and elegance and what Patricia Storace (in her description of turn of the twentieth-century Greek politician Ion Dragoumis) calls “…that most erotic of qualities in a man: the capacity for sustained concentration…,” that it’s hard to take your eyes off of him, and that I, at least, only manage to do so for fear of making a total ass of myself and because I want to let the guy do his job.

But Mono is for a really good dinner when you’re feeling rich and want to drop a lot of money on good wine that Ashley, the least pretentious and most generous sommeliere in the city, will help you out with. Today I just drop by at their annex next door, Bar Jamon, a place I also love, though if you don’t catch it at the beginning or end of the shift it’s always torturously crowded.

(It’s enough I haven’t given these places aliases; I’m not telling where they are on top of it; not everyone deserves to know.)

Jose is there today. Great! A Spaniard. After being sweetly told to go away at the gringo ashram because they were cleaning their chakras or something, I need an aggressive welcome and from a people who aren’t afraid of a little aggression. Jose always makes me happy because he’s a super-majo kid from Zaragoza in Aragon. Majeza is a very Spanish term that encompasses such a complex of qualities that it’s difficult to explain, especially in English, which is tragically lacking in a comparable term, as its speakers (aside from the Irish) are in most of its qualities. It means openness and frankness and humour and swagger; it means being hospitable without being in anyway servile; it means being able to put away copious amounts of wine and pig meat; being friendly and spirited and generous while always maintaining a kind of stylish dignity and flair; it partakes of some of the qualities of Greek and Turkish leventeia in that sense; in fact, it’s a word with a certain undoubtable Balkanness about it. Soon after the term appeared in, I think, the late eighteenth-century, working-class barrios of Madrid, it almost immediately became associated during the Napoleonic Wars with the city’s street kids, who terrified the French with their suicidal bravery, so it probably originally implied a quickness to pull a knife too and no squeamishness about seeing a little bit of your own blood shed as well. That doesn’t apply anymore, though the ferocity into which demonstrations in Madrid have descended these days makes you think twice about that; I’m proud of the angry tenacity of Spanish protests, mashallah; don’t know what they’ll accomplish but it’s good to know Spaniards can still be scary; that anger has become such a stigmatized, pathologized emotion in our civilization (“You know…I think you have a lot of anger…”) is partly what’s let banks and governments get away with what they have over the past few decades and generally has brought us to the civilizational crisis we find ourselves in. No, it’s not the other way around. In any event, courage is still certainly an implied element of being majo. There’s a great, chapter-long analysis of majeza in Timothy Mitchell’s Blood Sport: A Social History of Spanish Bullfighting, if you’re interested and can get your hands on it.

Jose’s bearing, humour and way of talking are the epitome of majete; I’m glad to see him, I’m hot, my feet hurt (“erkekler…pabucim sikiyor…”) and I ask him for a glass of anything cold and white. He immediately comes up with a great Albarino, a Galician wine I usually don’t like but this particular one is beautiful. I think of a gorgeous woman I was in love with a few years ago with blue-emerald eyes so intense they looked fake (actually her parents were Canarian – she just grew up in Santiago — so those eyes were probably Berber and certainly not Galician); she was beautiful, a good kid, and a little nuts – but beautiful.

“So a Greek and a Spaniard get together,” the joke goes — and of course these days they compare notes on how fucked up their respective countries have become. I tell Jose that I think Spain is salvageable but that Greece seems in danger of just slipping off of the face of the earth at some point soon. He’s not so confident. He says people in Spain are “learning to be poor again,” getting used to a life with “un plato de alubias” — a plate of beans — a proverbial Spanish expression for just-bare-subsistence poverty. He’s probably around thirty and he says bluntly that his generation in Spain is destroyed; that they’re going to hit their late thirties and early forties without any job experience and that unless you’ve got family money, your only option is emigration, like “old-time Gallegos” we both say in sync. (Galicians in Spain are like Epirotes in Greece, the archetypically emigrating region, so much so that in much of Latin America all Spaniards used to be collectively referred to as “Gallegos.”)

My heart goes out to him and I respect his straight-eyed stoicism and I think he’ll be ok because he seems strong. As hard as I try, though, my heart doesn’t go out to Greeks of his generation nor do I respect them. I think they’re cry-babies who would be scared shitless – or worse, think it beneath them — to work in a bar in New York the way Jose does and that they deserve – richly — to relearn the cultural lessons of emigration and being poor again. Three decades of illusory prosperity created an unbearable type of human being in Greece, a nouveau-riche culture of entitled provincials, cold, petty snobs who are snobs the way only the truly provincial can be – and I’m talking about Athens more than the provinces. (Athens is a city I genuinely love, but it probably ranks first in the world in thinking itself more sophisticated than it really is.) (Plus — I’m always confused a little by Cypriots, who arguably enjoyed a more solid prosperity for a longer time but never became so insufferable, and who all Athenians are always mercilessly condescending towards: incessantly mocking their clannishness, their still healthy respect for Church tradition, the beautiful musicality of Cypriot dialect.) I’m pained by the genuinely poor and the old and the sick and the heroin addicts who are suffering and dying in Greece, and murderously angry at Frau Merkel (“murderously”…you can quote me; I think she’s a criminal and should be gone after), who needs to pay banks back and dresses it up as one of her daddy’s Lutheran sermons. But that urban, middle-to-upper-middle-class, twenty-five to forty-five-year-old demographic in Greece…they can just go back to washing dishes in Chicago again like our grandfathers did as far as I care. Let ‘em start from scratch; see what kind of culture they can come up with this time.

(As I listen to Jose I remember that the terrifying Catalan Company, who are still a by-word for monsters and boogey-men in parts of the Balkans — “…like Catalani and the Devil,” Albanians say….Albanians — weren’t actually Catalanes at all, but savage Aragones highlanders: Jose’s ancestors.

The “Companyia Catalana d’Orient,” were a bunch of murderous, mercenary nut-jobs, the Blackwater of their day (I forget what Blackwater is called today) that had started off fighting in the Reconquista in Spain. But like the Greek-Arab Akritai-Ghazi of the Anatolian frontier, they were a mixed bag, originally mostly Arab-speaking Almogavars, an Arab word meaning “scout,” the “Muslims” eating pork and downing wine like good Iberians, the “Christians” proud that they raped nuns, looted monasteries and occasionally threatened the Pope. The only things these guys were loyal to were killing, looting and each other, in that order. This is their hymn:

Aur! Aur! Desperta ferro!

Deus aia!

Veyentnos sols venir, los pobles ja flamejen:

veyentnos sols passar, son bech los corbs netejen.

La guerra y lo saqueig, no hi ha mellors plahers.

Avant, almugavers! Que avisin als fossers!

La veu del somatent nos crida ja a la guerra.

Fadigues, plujes, neus, calors resistirem,

y si’ns abat la sòn, pendrèra per llit la terra,

y si’ns rendeix la fam carn crua menjarem!

Desperta ferro! Avant! Depressa com lo llamp

cayèm sobre son camp!

Almugavers, avant! Anem allí a fer carn!

Les feres tenen fam!

Listen! listen! Wake up, O iron! Help us God!…Just seeing us coming the villages are already ablaze. Just seeing us passing the crows are wiping their beaks. War and plunder, there are no greater pleasures. Forward Almogavars! Let them call the gravediggers! The voice of the somatent is calling us to war. Weariness, rains, snow and heat we shall endure. And if sleep overtakes us, we will use the earth as our bed. And if we get hungry, we shall eat raw meat. Wake up, O iron! Forward! Fast as the lightning let us fall over their camp! Forward Almogavars! Let us go there to make flesh, the wild beasts are hungry!

Boy, people don’t like war like they used to, do they? Even Marine chants aren’t this hard-core. Or do they? And it’s just shape-shifted into something else?

I think they were actually involved in one of the Crusades and then at one point one of our last moronic emperors had the brilliant idea of inviting them as mercenaries to help fight off the Ottomans. What scheming idiots, except for poor, tragic Constantine, the Palaiologoi were — and poor Kyr Gianne Cantacouzino, so beloved by Cavafy, trying to hold together the mess they created. And they weren’t even good schemers, which is one thing Greeks usually do well. Even Constantine tried to interfere in the succession of Mehmet II in a pathetic way that had worked before but by that point the Turks were on to them already. He sent a delegation to Edirne to remind the new Sultan’s vezir that they held Mehmet’s brother Orhan as a guest in Constantinople, a veiled threat of provoking another succession civil war among the Ottomans, which wasn’t hard to do given the brutally absolutist methods Ottoman succession practices involved. I always loved the balling-out the Greek diplomats got from Halil, Mehmet’s vizier:

“You stupid Greeks, I have had enough of your devious ways. The late Sultan was a lenient and conscientious friend to you. The present Sultan is not of the same mind. If Constantine eludes his bold and imperious grasp, it will be only because God continues to overlook your cunning and wicked schemes. You are fools to think you frighten us with your fantasies, and that when the ink on our treaty is barely dry. We are not children without strength or reason. If you think you can start something, do so… All that you will achieve is to lose what little you still have.”

This is what they were left with in 1400. At the time of the above event, which was fifty years later, they had lost Salonica too and almost all of the Thracian hinterlands of C-town itself. But it was still “The Empire of the Romans.”

As for the Aragoneses the century before, they succeeded in inflicting some damage on the Ottomans at first, but had soon attracted Turkic and Greek freelancers into their ranks and of course went on a decade-long plundering spree in both Byzantine and Ottoman lands, including Mount Athos, where no Catalan was allowed to enter until recently, and only upon payment of reparations by the government of Catalonia; those monks have Byzantine memories, man. After devastating the countryside of what remained of the Byzantine empire, they established a Duchy for themselves at Athens by taking it from some other Frangoi, which was eventually absorbed by the Ottomans, of course, though the King of Spain still carries the title, “Duke of Athens,” which the Spanish Crown inherited through the Kingdom of Aragon.)

I snap out of my historic daydreaming and pay for my Albarino and my incredibly expensive plate of ham, which was totally worth it. It was Iberico ham from pata negra pigs from Extremadura that eat free-range, mostly acorns, so the meat is grained with a velvety fat that has an incredibly nutty taste to it and a texture unlike any other kind of pork fat. It wasn’t allowed into the U.S. until recently because the F.D.A. or whoever had concerns about the health standards under which the pigs were raised, like they’re worried about raw milk cheeses and I don’t know what else. I think of how irritated I get when I have to fill out an American customs form when I’m coming to the U.S. and I get to that question about whether I have any agricultural products on me. I’m like: “Are you serious, United States of America? Are you really asking me this question? You? The origin of all the plastic, poisonous, carcinogenic garbage food on the planet? You’re really worried about two lemons from a family orchard or some sausages I might have with me and the havoc they’re going to wreak on America’s ecosystem and agriculture? Really?”

Jamon Iberico at Mono (click)

I wish Jose well, hope to have enough money to see him again soon because I’m broke these days, and head for the N back to Queens. I expect more stimulation on the subway and am not disappointed. But the first thing I notice is a great drawing, by an artist whose name I’m too stupid to note, that covers the entire ad space above the bench opposite me. It’s a Bemelman-like drawing of New Yorkers on a subway bench, like the one we’re all sitting on and they’ve got it posted on both sides of the car, in fact.

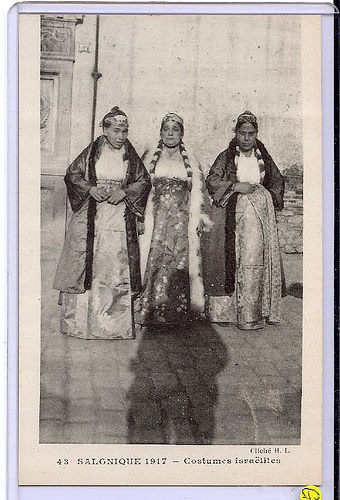

I immediately do a double-take because it looks like two of the characters in the drawing are two little Dropolitisses, women from my father’s villages in southern Albania, with their distinctive white headdresses, like my grandmother here in the last photo we have of her. (click on all)

Then I look closer and notice their sneakers and schoolbags and realize they’re two Muslim high school girls sharing an IPad. I smile, because the implications of and reasons for confusing the two are so obviously telling.

On the bench below the drawing are two big, sun-burnt Irish construction workers, in cut-off jeans and work-boots, t-shirts with dried sweat stains on them, who are so exhausted that they are falling asleep on each other. Somehow, though, I know they’re gonna go for a pint when they get off the train, no matter how exhausted. At the other end are three lanky, Bosnian giants, who have to keep their legs doubled up against their midsections practically to keep them from stretching across the whole subway car. I stare at them with a dumb unconscious stare, listening to the subtle tonality of Serbo-Croatian (or “Bosnian”), as they goof around with each other, and I think they’d be fun to drink with – if they drink (they probably drink…). Then suddenly the image of all that manhood and youth decomposing and scattered around the ground in pieces flashes before my eyes (I’ve had Srebrenica on the brain for the past few days too, not just faloodeh), and I snap out of it.

In the middle of these two bunches of heavy-weights is a super-elegant Pakistani kid, with a white-stitched topi on his head, with the v-shaped opening that Sindhi topis have though I don’t know where he’s from, and a carefully trimmed beard that’s always a sign of observant-but-not-nuts to me. He’s got cool blue suede Adidas on and perfectly ripped jeans so you can see the hair against the color of his skin on his thighs and shins. He’s got a worn wooden tespih wound around his left wrist along with a thick leather wrist-band and about half a dozen multi-color, tie-on bracelets that could’ve been bought on the beach in Cancun on his right. But on top of it all he’s wearing a stunningly beautiful, blindingly white, short-length kurta, completely unbuttoned down to the middle of his chest, with a dense white-on-white chikan-like embroidery around the collar and button panels that even from across the subway car I can tell is exquisite (my mom taught me to recognize good needlework; she was a very skilled embroiderer herself). I know this simple summer kurta and its kind of embroidery can cost as much as a good sherwani, and I wonder where he’s going or coming from to be wearing such an expensive piece of clothing. He’s also got his sunglasses balanced behind the back of his head, and they don’t slide off during the whole subway ride. This is Desi majeza. He’s a sight. I wonder if they’ve found a suitable girl for him yet, or if he’s even going to tolerate family choices in that kind of thing; see, that’s the thing; his whole get-up and attitude make it impossible to gauge exactly how “traditional” he is, a frequent dilemma in a city where the cultural self is so malleable, and which – aside from how handsome he is – is what makes him so fascinating to look at. He could be the perfect obedient Muslim son; he could be a D.J. somewhere or a dancer regular at Bhangra Basement at S.O.B.’s or an ecstasy dealer, or all or any combination of those. I bet he drinks. I bet he fasts for Ramazan though. I then start wondering what Whitman, who loved the men of New York so deeply: “manners free and superb—open voices–hospitality—the most courageous and friendly young men…” would have done with the material New York would have to offer him these days. He wrote with such passion of a totally white city; he might’ve been overwhelmed by this one.

I like betting to myself where people are going to get off the subway based on sociological info, and, of course, the Irish guys and the Pakistani get off at Queensborough Plaza to take the 7 train, the Irish guys to Sunnyside or Woodside, the cool Pakistani kid to Jackson Heights or Elmhurst. And sure enough the Bosnians follow me to Astoria. I think to myself that I should get a camera and a business card for this blog so I look semi-professional and not like a freak asking people if I can take their picture with my lame Blackberry.

The N train (photo: Matt Lawson)

In Astoria I catch the end of vespers at Hagia Eirene. This is a church that used to be the territory of fundamentalist, Old Calendar, separatist crazies but has rejoined the flock on the condition that it was granted monastic status (and I have no idea what that means). But it has somehow got its hands on a great bunch of cantors and priests who really know what they’re doing. I’m impressed. I brought friends here for the Resurrection this year and for the first time I wasn’t embarrassed. If I hadn’t invited them back home afterwards I would have stayed for the Canon. Only one cantor now at vespers but he’s marvelous and the lighting is right and the priest’s bearing appropriately imperial. It’s incredibly heartening to see our civilization’s greatest achievement — which is not what the Frangoi taught us about Sophocles or Pericles or some half-baked knowledge of Plato or a dumb hard-on about the Elgin marbles or the word “Macedonia,” but this, the rite and music and poetry and theatre of the Church – performed with the elegance and dignity that it deserves.

From the wall paintings at Hagia Eirene: St. Demetrius above, my patron saint, and his best army buddy, St. Nestor, below, executed together by the Emperor Maximian in Salonica in 306 A.D., because Nestor, with Dimitri’s blessing, killed the Emperor’s favorite gladiator in the arena. Nestor was beheaded; Dimitri run through with lances — a story. (Click)

I end up back in Sunnyside, which has become a heavily Turkish neighborhood in recent years. The amazing thing is what a complete range of Turkish society the community consists of. Every kind of Turk: from gorgeous young Istanbullu girls (who have disconcertingly started to destroy their beautiful faces with bad nose jobs, like Iranian girls), to old women in flowered salvar squatting outside on the steps of the neighborhood’s Art Deco apartment buildings, picking through lentils in a big sini. On the corners are Turkish guys hanging out or you pass one every few yards as you walk down the street (“…icim sikiliyor”) and once again I curse the fact that “man torki na midaanam.”

Ah, here’s some Hafez:

“I am the slave of the eyes of that Turk who, in his sweet drunken sleep,

Has a canopy of musky eyebrows over the adorned rose-bed of his face.”

(Sorry I don’t know the Farsi.)

Of course these guys don’t look like Hafez’ Turk would have, don’t have the eyes he would have, nor do they look like the Uzbek beauty that served me my faloodeh earlier in the afternoon. These are “our Turks” and though quite a few do, the majority don’t bear much resemblance to their Turkic forebears anymore. I said that once in a conversation with some Greeks – “our Turks” – to distinguish the inhabitants of Turkey from Central Asian peoples (I don’t know what we were talking about that making that distinction would have been necessary) and I got a blank stare from everybody. But after a brief pause I realized that it felt good to say, that it was heart-warming to say: “our Turks.” Plus, anything like that I might say that pisses off Greeks gives me a thrill that can’t be described.

I was once so mad for a Turkish guy from Sunnyside years ago that I learned how to write: “___________, you’re beautiful” in Ottoman script and graffitied it all over the neighborhood. I thought it would be like a coded love-letter from his ancestral past and that somehow, some day, God would see to it that it were decoded for him. Thank God that I don’t think He ever did because today I’m mortified to even remember that I did something like that — not that it’s exactly out of character. I have much to be mortified over; and it takes much longer than you think to convert humiliating regrets into “ah-youth” nostalgia. And I wasn’t so young either. It’s just this guy was a knock-out. He’d walk into a bar and my knees would get shaky; I’d have to be trashed to talk to him without stuttering. I had to let it out somehow or I would’ve died.

I drop into my favorite Irish pub on Queens Boulevard, for a beer and to wait for a friend and, sure enough, it’s full of dusty, sweaty construction workers who couldn’t go home without a pint. Despite the influx of Turks and Greeks and Roumanians and Armenians (it’s one of the mysteries of New York immigration that peoples who can’t stand each other back home choose to settle in the same neighborhoods when they get here), Sunnyside is still one of the city’s hard-core Irish neighborhoods, with a population of both old-time Irish-Americans and young Irish kids. These last had stopped coming for a while, but now have sadly started again, afflicted by the eternal curse of this beautiful, heroic people. But they, for sure, are tough enough for anything. When you talk to them about things in Ireland, they’re attitude is basically: “Ah…young folks leaving again…things were good for a while, ya know, and now we’re back to the same old….cheers…”

The 7 train in Sunnyside. The only attempt ever made in New York to make an elevated train attractive. (click)

There was a genre of Ottoman literature known as the “shehrengiz,” the “shehrashub” in its Farsi prototype, which was basically a tour of a particular city cataloguing in detail all its beautiful people: men and women, but mostly young men — echoes of Whitman again. Walter Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli in their fascinating and highly idiosyncratic The Age of Beloveds: Love and the Beloved in Early Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society translate the term as “city-thriller” or “city-disturber.” One of the longest extant ones is about Gumulcine oddly enough (Komotene), ironic because the only thing that distinguishes modern Gumulcine from any miserable northern Greek city and makes it interesting and quite beautiful is its Turkish population. People have called this corner of Greece the last remaining part of the Ottoman Empire and it truly feels that way. The Turkish marketplace there is particularly fascinating, because of its abundance of coffeehouses and borekcidika, but also because of the beautiful traditional jewelry that’s still made in the city and sold in its numerous shops. This isn’t the mass-produced crap of Jiannena; this is stuff of real artistry. Wonder what the boys who worked in its sixteenth-century jewelry workshops looked like; they were obviously of high poetic caliber.

(Once when I was in Komotene I had spent the morning in the Turkish market neighborhood and later on, for some reason, walked back through its streets during siesta time, when all the shops were shuttered. I saw that the iron gate of every single shop in the marketplace had “1955” graffitied on it, the year of the anti-Greek riots in Istanbul – see one of my first posts “The Name of this Blog”. I thought it was the creepiest, most cowardly kind of nationalist intimidation that I’d ever seen; it still turns my stomach to remember it.)

Gumulcine

One more beer as it starts getting dark. Today I lived my own New York shehrengiz. Sorry for the rambling length of this post, or if any part of it was embarrassingly personal; feel for me. I felt compelled to write it — my prose shehrengiz. It started with the faloodeh. It’s what a hot summer day in New York can do to you.

I am he that aches with amorous love;

Does the earth gravitate? does not all matter, aching,

attract all matter?

So the body of me to all I meet or know.

— Walt Whitman

**********************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

*The name of this entry is the name of one of the all-time greatest hits of the legendary Puerto Rican salsa band, El Gran Combo, “Un Verano en Nueva York” , “A Summer in New York:” “If you want to have fun, full of enchantment and delight, all you have to do is live a summer in New York.” Of course, given how hellish summer in New York can be, especially for inner-city residents, especially back in 1970, I always had this weird suspicion that this song was some kind of sick joke…

**Of course as fate would have it — or I must’ve insulted some goddess, Artemis, or Durga Ma probably — a couple of months after I wrote this there was suddenly a woman behind the kitchen bar at Mono and of course she’s great and of course I keep going.

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com