“Oh, is that what it’s called?” I remember saying to myself when last summer’s protests erupted, and I suspect I was joined by quite a few lovers of İstanbul and even natives when they found out that the scruffy, forlorn lot north of Taksim and behind the Arab nargile places along the Cumhurriyet actually had a name. I may have spent about four or five accumulated months of my life in İstanbul over the years and I think I’ve been inside this park once; one look is enough — and the much bandied-about slogan about “saving the last green space in central Istanbul” becomes comical. A sudden nostalgia for the place sprang up at the time; everyone suddenly had memories of playing there as a child, but they didn’t seem very convincing. Nobody cares about Gezi park. Or did last summer.

What young Turks cared about was Taksim, but even more the string of neighborhoods south of Taksim to Karaköy and their enormous importance in the life of İstanbul. Proof enough – and weighty proof at that – is that serious civil disobedience began in the area back in the spring, not when the government tried to start construction in Gezi, but when it tried to impose limitations on alcohol consumption in the neighborhood. Remember the alcohol – it’s a central part of our story, enough for us to maybe have called the whole upheaval the Rakı Revolution and not the Taksim/Gezi protests. But somehow the press and the people itself forgot that. Somehow that got lost as the movement morphed into a catch-all protest with a not particularly convincing “green” bayraki propped up as its mascot in a shabby, dirty park.

Unclear? Yes. It is to me too and I’m sorting it out as I write.

It goes like this: Pera and Galata — because those are the core areas of the municipality of Beyoğlu that really concern us (Taralabaşı too but as a side show, another story) — were, until the middle of the previous century, heavily Greek. And Armenian and Jewish, but Greek enough so that pidgin Greek was the quarter’s common means of communication till the early nineteen-hundreds. Pera and Galata were centers of non-Muslim life in İstanbul and Pera and Galata were where you went to drink. Not a coincidence obviously. And Pera and Galata are still where you go to drink and party – in fact even more than ever. And that’s why the fact that attempted restrictions of alcohol consumption set off the civil disobedience of 2013 is so important.

The tourist literature and the press never tire of calling this the center of contemporary Istanbul and tourists who used to stay in Sultanahmet and wonder at the eerie emptiness of the old city’s streets at night have finally started to discover the area – the “Old New Town” as Alexandros Massavetas calls it in his loving, lyrical Going Back to Constantinople: a City of Absences. And truly, as I’ve written before, these neighborhoods dominate the contemporary social and cultural life of İstanbul in a way that’s not comparable to any other major metropolis I’m familiar with.

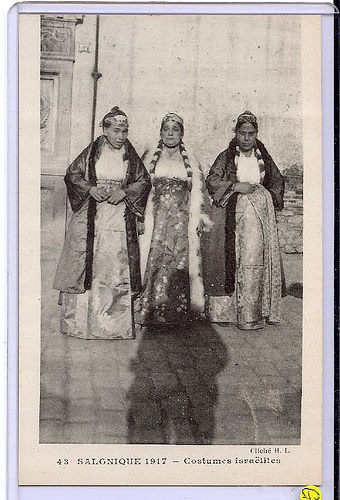

The neighborhoods we’re talking about, Beyoğlu, with Pera (“over there” in Greek, meaning from the old Byzantine/Ottoman city) at its center. (click)

And here we run into our first paradox, or the origins of a chain of paradox: that this now central “heart” of İstanbul began as a space of marginality. The Byzantines originally put some of their unwanted Catholics there: Galata’s mother city is actually Genoa. In Ottoman times, Christians and Jews lived there and made wine and everybody else came there to drink it. While not an exclusionary, extramural ghetto of any sort – to their credit the Ottomans didn’t often do that kind of thing – it was sort of the wrong side of the tracks: the Ottoman equivalent of the suburbs or the across-the-river Zoroastrian neighborhoods in Iran where Hafez and company went to drink the infidel’s wine and torment themselves with the beauty of the innkeeper’s son: the other side of town, the refuge of disbelief and transgression, of unorthodoxy and the unorthodox in every sense. The alcohol…

The nineteenth century marked Pera and Galata’s – Pera’s especially — transformation into uprent enclaves: gentrification avant-la-lettre in effect. The Christian-ness of the area only attracted more of them, then foreign Europeans; the influx of non-Muslims from the rest of the city concentrated its gavur character even more deeply. There were foreign embassies. Foreign embassy cultural activities followed. Cafés. Theaters. Neoclassical Row houses and apartment buildings in an eclectic mix of local versions of the Neoclassical or Art Nouveau. All the apparatus of contemporary European urbanity developed: a place of often obscene display of non-Muslim privilege that reminds one of Durrell’s Alexandria or descriptions of the foreign concessions in Shanghai before the revolution, and increasingly alienating to the average un-Westernized Muslim. But a city. One as we mean it. In the Benjaminian sense. With everything that the modern city at the time implied and still does: socializing and the public space, boulevard culture, entertainment, exteriority… WOMEN… Alcohol, of course… And with Kyr Panos’ taverna and Monsieur Avram’s textile shop still flourishing alongside.

The Jadde at its height, probably early Republican times, by the gates of Galatasaray Lycée (above). This was the neighborhood known as the Staurodromi by Greeks, the “crossroads” because it’s where the Grande Rue meets Yeni Çarşı Caddesi (the New Market — not sure what that referred to — food market around Balık Pazarı?) (Click) Bottom photo is by Ara Guler*

And then all the Kyr Panoses and the Monsieur Avrams went away, for reasons readers know and this blog touches on often and will inevitably look back at again. And this “center of the city” sat in a kind of rancid aspic for a few decades until a young and dynamic and sophisticated Turkish society reclaims it. And it comes alive again. And yet the paradox still stands, now sharper than ever (though how conscious and to whom is very much up for debate and may be my real question): that this is the cosmopolitan center of İstanbul; but what made it cosmopolitan were populations that don’t live there any more, but whose legacy is in both the air and breath of the place and in its physical matter itself. And what we, Turks today, do about that – how we reconfigure a center of our city so laden with the presence and absence of others in order to suit our contemporary needs – is, to a great extent, what progressive Turks and Erdoğan were fighting about last summer. Not Gezi park.

Some of Erdoğan’s ideas don’t seem so bad to me; a tunnel for one (already built?), that as I gather goes under in Dolapdere and emerges somewhere in Kabataş I think, that would finally free Taksim, never an aesthetically promising piece of real estate, from having to be a major traffic circle, though Harvard’s Hashim Sarkis’ idea that: “We know from the 1960s that pedestrianizing everything doesn’t work…Managing the balance is better…” makes sense, and I often wonder about the wisdom of having pedestrianized the İstiklal itself. The (now aborted?) reconstruction of the Ottoman barracks may turn out to be a piece a kitsch, but you never know. In Moscow, for example, much that was destroyed by Stalin has been carefully reconstructed and it’s lovely; and some of the rest unnecessary, and garish – and often silly. Either way, I wouldn’t miss the park.

The true big elephant in the Taksim room is a big old elephant of a Greek church that lords over the whole space. The church of the Hagia Triadha is one of the post-reform churches of İstanbul, churches that were built during the Tanzimat, when traditional restrictions that imposed visual discretion and inconspicuousness on non-Muslim places of worship were lifted and Greeks in İstanbul built some very conspicuous –and often conspicuously ugly — churches. The Hagia Triadha is actually one of the lovelier of them – it reminds me of the Balyan mosques a little – and gives you a real sense of just how confident Greeks in the City felt in the late nineteenth century. But its presence is almost impudent; I can only imagine how more traditional Ottoman Muslims must have felt as they saw these giants go up after the 1850s, and to be honest as I’ve walked by at times even I’ve found myself overtaken by what I can only describe as a mild shtetl-anxiety and thinking: “But so big? And right here? Can this be good for the Jews?” So you can imagine that to Erdoğan and the Turkish Islamist mind its bulk must be doubly provocative, and presents a problem that needs to be solved. The “central square” of the “modern center” of İstanbul just can’t be left looking so…well…so Christian.

The church of the Hagia Triadha alone and surrounded by its kebab shops. (Click on both)

And another aerial view of the church, the school and surrounding area that gives a clearer idea of layout (click)

So Erdoğan is going to make good on a long-term promise/threat to build a large mosque there to balance out the religious character of the space. First, he’s going to tear down the circle of döner and kokoreç stands that surround the Hagia Triadha and the neighboring Zappeion, once İstanbul’s most elite Greek school for girls, which is a shame because a circle of smoking lamb fat wafting around the billowing clouds of a church’s incense was always a beautiful olfactory image to me – this is what the Temple must’ve smelled like – and because neighborhood partiers will be deprived of much-needed early morning sustenance. But philistines like Erdoğan don’t like the smell of lamb fat – probably too familiar — or as Auntie Mame might have said, when you’re from Kasımpaşa you have to do something, so the döner stands will have to go. And I originally had no sources for this other than my own suspicions, but I was wondering if the döner stands aren’t part of the church’s vakoufia (religious trust properties) and that removing them is another act of expropriation of Greek community real estate that has been going on steadily for decades now; and the Greek community is indeed split into warring camps already about whether taking down the stands is expropriation of parish property or is a good thing; only Greeks can be reduced to a community of about a thousand people, mostly over seventy, and still find energy to bicker about everything; but then there are two Jews left here in Kabul — two –and they’re not speaking to each other over some maintenance issue concerning their one synagogue. Anyway, the official claim, however, is that the food stands will have to go – get this — in order to make the church more visible so that it and its new neighboring mosque can clearly stand side by side as confessional brothers in the new, beautified Taksim. Turkey has tried desperately over the past few decades to gain political and cultural capital through gross multicultural gestures of this sort. This has to be the most nauseating example to date.**

The English-language coverage of the protests paid only the scantest attention to issues of this sort. Even this piece from the New York Times by Michael Kimmelman: “In Istanbul’s Heart, Leader’s Obsession, Perhaps Achilles’ Heel,” about the reconstruction of Taksim managed to not include a single photograph of the Hagia Triadha, which is quite hard to do actually and, were I a bit more of a conspiracy theorist, would think might be intentional. As to the former ethnic composition of the area, all reference to the area’s former cultural and linguistic character is colored by the inability of Western — whether American or European — thinkers, to think about multiethnic societies outside of the immigrant societies they know. In this piece also from the Times that prompted my Tarlabaşı series, “Poor but Proud Istanbul Neighborhood Faces Gentrification,” Jessica Burque says: “Migrant workers have a long history of living in Tarlabaşı, dating from the early 1900s when Greek, Jewish and Armenian craftsmen lived in the area” — no sense that they had belonged to the city for generations, centuries before 1900. And the above referenced article by Kimmelman refers to Beyoğlu as an area where: “poor European immigrants settled during the 19th century.” — no sense that these people were natives of the city, often of communities that predated the Ottomans, or that they were essential component parts of Ottoman society, from other parts of the empire perhaps, but not outsiders or “immigrants.” There’s often some vague reference to the buzzwords “diversity” and “cosmopolitan” and no serious mention of what drove the “cosmopolitans” and “migrant workers” away; again a perception that seems informed by seeing this all through the prism of the American immigration experience: as if Pera were a neighborhood on the 7 train, let’s say, and its Dominicans have now moved on to the greener suburban pastures of Bayside.

Unfortunately I don’t know if the Turkish press made any reference to the area’s former social composition when covering the protests or if any Turks did at all. The closing of İnci, the patisserie, is what most brought this all home to me: “the closing of the historic Emek cinema and a much-loved pastry shop…” There was quite a fuss about İnci apparently, but was any mention made at the time that this had been one of the last Greek businesses in the neighborhood? There are two more left in all of Beyoğlu I think, İmroz, the restaurant on Nevizade and, perhaps the only growth industry in Greek İstanbul, a coffin-maker’s near the Panayia in Stavrodromi. Inci had been there since 1947. I leaf through Speros Vryonis’ massive “The Mechanism of Catastrophe”*** to the pages containing K. Ioannides’, a journalist from the Salonica-based Macedonia newspaper, cataloguing of ransacked Greek businesses in the area, which means all of them, without exception. On just the İstiklal Caddesi, Meşrutiyet Caddesi, Pasaj Evropa, Yüksek Kaldırım and Perşembe Pazarı there is a list of three-hundred and twenty-nine businesses. And you really have to marvel and wonder at whether the Greek “daemon” is more than a myth.**** After the financial decimation of the community by the Varlık Vergisi, the “estate tax” of the 1940’s, when discriminatory taxation against minority groups had wiped out many, and sent many of those who couldn’t pay to forced labor camps, Greeks had bounced back to dominating the retail business of these central neighborhoods in less than a decade – only, of course, to have it all definitively trashed a few years later. And, sure enough, there it was, at number 27 on the list: “Pastry shop İnci of Loukas and Lefteres.” When people mourned the loss of İnci last summer, was there any sense that something more than a charming old patisserie was disappearing? Or that this was a place that had bounced back from total loss in one Istanbul tragedy and then went on to continue serving the city for more than fifty years?

İnci, before and during protests, after closure.

What do I want exactly?

All – I thought a lot about whether I should use “almost all” in this sentence and decided against it –because all the hippest, funkiest, most attractive, gentrified neighborhoods in the historic parts of İstanbul are neighborhoods that were significantly, if not largely, minority-inhabited until well into the twentieth century: not just Pera and Galata, but Cihangir and Tarlabaşı, and even Kurtuluş — of course — and up and down the western shores of the Bosphorus and much of its eastern towns too, and central Kadiköy and Moda and the Islands. (And if serious gentrifying ever begins in the old city it’ll be in Samatya and Kumkapı and Fener and Balat; I wouldn’t put any big money into Aksaray or Çarşamba just yet.) If young Turks are fighting to preserve the cosmopolitan character of areas made cosmopolitan by a Greek presence, among others, is it a recognition of that presence, however vestigial, that I want? Yes. Is it because some recognition might assuage some of the bitterness of the displacement? Perhaps. Is the feeling proprietary then? Does the particular “cool” quality of these neighborhoods that protesters have been fighting to protect register for me as a form of appropriated “coolness?” I’m afraid that yes, sometimes it does. In darker moments this spring and summer, these Occupy Gezi kids annoyed me: “What’s wrong mes p’tits? The Big Daddy State threatening to break up your funky Beyoğlu party? Do you know the Big Daddy State made life so intolerable for the dudes who made Beyoğlu funky that they not only had to break the party up, but shut down shop altogether and set up elsewhere? That your own daddies and granddaddies probably stood by and watched, approved even? Do you know that now? Do you care?”

Cleaning up in a Greek neighborhood after the pogrom of 6-7 September 1955. I’ve spared readers and myself more and worse photos. (Click)

Cleaning up in a Greek neighborhood after the pogrom of 6-7 September 1955. I’ve spared readers and myself more and worse photos. (Click)

No one in New York would think of talking about the Lower East Side, for example, or the Bronx, without due respect to the Jewish role in the formation of those areas and, by extension, every aspect of New York culture. You mourn the passing of every Ratner’s and Second Avenue Deli even if you aren’t Jewish and even if five of them take their place in Kew Gardens or Borough Park. Or to use a significantly more heated example: if the young white professionals now moving in large numbers into Harlem refused to acknowledge that Harlem’s atmosphere, style, musicality — that the whole Harlem phenomenon — were largely African-American contributions to the city’s life, wouldn’t any culturally or historically conscious New Yorker find that problematic or reprehensible; not to mention how the neighborhoods Blacks would feel (and do…) And Jews and Blacks were never driven out of New York by a systematic campaign of violence, harassment, confiscation and forced expulsion.

Therefore: If 2013’s protests then – at least İstanbul’s –were at their core about protecting aspects of the essential urbanity of İstanbul, and Greeks played such a large role in shaping that urbanity, shouldn’t that be acknowledged? If Turkish society is playing out – again, at least in İstanbul – its most intense culture wars on a ghost blueprint of vanished minorities, then wouldn’t making that a more explicit part of the contest be immensely productive – all around?

But these grudges are usually not this deep and usually don’t last long. Partly because I’m always on the side of the partiers – any partiers. Partly because I trust the growing consciousness and honesty of most young Turks. The protesters as a rule behaved so civilly and politely, their chants and slogans so witty and intelligent for the most part, that you couldn’t help but be impressed. As opposed to Erdoğan and his party’s grand Haussmanian plans, I think they didn’t really want much: Gezi was just a convenient object. I think they want the area neither Islamized and Neo-Ottomanized or “re-Republicanized” as it were. I think they’re tired of those two poles, and as a close friend of mine said, they want another option. I think they wanted the neighborhood to stay as it is and always has been: a place of pleasure and freedom and difference, of uncomfortable, musty cinemas that offer something more interesting than the suburban multiplexes, of Art Nouveau cafes, no matter how garishly over-renovated or turned into fast-food lunch shops, of badly lit meyhanes that you have to know to find, a couple of gay bars, of mini-skirts and transvestites – both separately and together — everything that the strange sensuality of Istanbul offers and the freedom to not be told how and when to enjoy it. Every man’s inalienable right to want a sweaty glass of rakı and some leblebi or a good mojito when he wants it.

And they’ll win too. Just as Hafez says:

Might they open the doors of the wine shops

And loosen their hold on our knotted lives?

If shut to satisfy the ego of the puritan

Take heart, for they will reopen to satisfy God.

— Kabul, November 2013

*********************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

* Two more of Güler’s most famous photographs:

While there’s no documentation that the subjects of these photos are Greek, the period, the neighborhood they were taken in and — well — just their look, seem to say so. Ara Güler was a prolific photographer whose work has been sadly overexposed by excessive postcard-ization. He once famously said: “Today, 13 million people live here. We have been overrun by villagers from Anatolia who don’t understand the poetry or the romance of Istanbul. They don’t even know the great pleasures of civilization, like how to eat well. They came, and the Greeks, Armenians and Jews, who became rich here and made this city so wonderful, left for various reasons. This is how we lost what we had for 400 years.”

He was called a racist by many leftists for that comment. But who pays them any heed? His website: Ara Güler: Official Website

** For more of my thoughts on the hypocrisies of multi-culti İstanbul nostalgia see my early piece The Name of this Blog, and my series Tarlabaşı I, Tarlabaşı II, and Tarlabaşı III . Especially see Amy Mills’ Streets of Memory: Landscape, Tolerance, and National Identity in Istanbul based on her research in the Bosporus suburb of Kuzguncuk, where she argues that nostalgia for the cosmopolitan actually serves to erase minorities and discrimination against them from public memory and reinforce Turkish Republican ethnic homogeneity. I think that’s exactly what’s happening in Beyoğlu.

*** Speros Vryonis The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom Of September 6 – 7, 1955, And The Destruction Of The Greek Community Of Istanbul is a magisterial life’s work and piece of historical journalism that covers the one night of September 6-7, 1955 in which a pogrom organized by Adnan Menderes’ Demokrat Parti destroyed practically the entire commercial, financial, ecclesiastic, educational and domestic infrastructure of the City’s Greek community. I had put off reading it for quite a while — because the subject matter is upsetting and it’s long and detailled — but I was really impressed when I finally did. I hadn’t realized the exact extent of the damage: 4,500 Greek homes, 3,500 shops and businesses (nearly all), 90 churches and monasteries (nearly all), and 36 schools destroyed and 3 cemeteries desecrated. I hadn’t known that so many homes had been destroyed, leaving a large part of the community of then 80 or 90,000 or so homeless and destitute and that, as opposed to the traditional account of one old monk being burned alive, some 30 people were actually killed and many raped.

The Menderes government initially, and stupidly, tried to portray this as a spontaneous outbreak of nationalist fervor against Greeks over growing Cyprus tensions, but it was actually an extremely well-planned and executed military manoeuvre (every Turk, after all, is a soldier born) carried out and directed by local cadres of the Demokrat Parti who knew their neighborhoods and its Greek properties and institutions well and through the use of Anatolians brought in from the provinces; I guess they were afraid that local İstanbullus, who knew and lived with these Greeks, would not be as easily destructive, though the record of how the city’s Turks did act during the riots is hardly edifying. As all products of the nationalist-militarist mind, the plan was an extremely stupid move as well. It brought the economy of Turkey’s largest city to a virtual standstill, at a time when the country was in deep economic doldrums to begin with, by ripping out its retail heart, so much of it being in the hands of Greeks and other minority groups, and in the immediate aftermath there were chronic shortages of basic supplies in the city because distribution networks had been completely severed and even bread — so many bakeries being Greek and Epirote, especially, owned — was hard to find. It temporarily made Turkey an international pariah (though in that Cold War climate that didn’t last too long) and eventually played a role in bringing the Menderes government down and costing him his life — thought that all is well beyond the scope of this post, this blog and my knowledge. Vryonis’ analysis is brilliant if you’re interested.

It’s become axiomatic that the riots were the beginning of the end of Greek Constantinople; the community struggled and tried, but this time things were shattered — physically and psychologically — beyond repair.

**** The Greek Daemon, “daemon” in the Roman sense of the word of animating genius — “To daimonio tes fyles” — is the idea that Greeks are resourceful enough to prosper anywhere and under any conditions — Patrick Leigh Fermor’s belief in their ability to “spin gold out of air” — and the repeated tragic setbacks and almost immediate comeback of the Greek community of İstanbul after nearly every catastrophe to befall it in the twentieth century tempts one to believe in its truth. Thus, one of the most poignant elements in the Constantinopolitan story is their almost masochistic refusal to leave — what it took to finally make the vast majority abandon the city they loved so much was just too overwhelming in the end however.

There is one important corollary to the “Greek Daemon” myth, however: it only operates for Greeks outside of the Greek state itself, and unfortunately history seems to continue to bear this out.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

(Murad Sezer/Associated Press)

(Murad Sezer/Associated Press)