In a truly disturbing op-ed piece in the Times: “Charlottesville and the Bigotocracy“, Dayson makes the same point I made in “Ireland — Gimme a break; I can’t believe this is even up for discussion“.

White nationalists and neo-Nazis demonstrated in Charlottesville, Va., on Saturday. Credit: Edu Bayer for The New York Times

White nationalists and neo-Nazis demonstrated in Charlottesville, Va., on Saturday. Credit: Edu Bayer for The New York Times

“This bigotocracy overlooks fundamental facts about slavery in this country: that blacks were stolen from their African homeland to toil for no wages in American dirt. When black folk and others point that out, white bigots are aggrieved. They are especially offended when it is argued that slavery changed clothes during Reconstruction and got dressed up as freedom, only to keep menacing black folk as it did during Jim Crow. The bigotocracy is angry that slavery is seen as this nation’s original sin. And yet they remain depressingly and purposefully ignorant of what slavery was, how it happened, what it did to us, how it shaped race and the air and space between white and black folk, and the life and arc of white and black cultures.

“They [white supremacists] cling to a faded Southern aristocracy whose benefits — of alleged white superiority, and moral and intellectual supremacy — trickled down to ordinary whites. If they couldn’t drink from the cup of economic advantage that white elites tasted, at least they could sip what was left of a hateful ideology: at least they weren’t black. [my emphasis] The renowned scholar W.E.B. Du Bois called this alleged sense of superiority the psychic wages of whiteness. President Lyndon Baines Johnson once argued, “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.””

From my post:

“But everybody has to be better than somebody, or else you’re nobody. So, just like Catalans have to think they’re really Mare-Nostrum-Provençal Iberians (3 ***) and not part of reactionary Black Legend Spain; or Neo-Greeks have to think that they’re better than their Balkan neighbors (especially Albanian “Turks”) because they think they’re the descendants of those Greeks; or the largely lower-middle class, Low Church or Presbyterian or Methodist Brits who fled their socioeconomic status back home and went out to India in the nineteenth century in order to be somebody, had to destroy the modus vivendi that had existed there between Company white-folk and Indians, creating an apartheid and religiously intolerant social system that laid the groundwork for the unbelievable blood-letting of the Indian Rebellion of 1857; or, perhaps history’s greatest example, poor whites in the American South (many, ironically, of Northern Irish Protestant origin) that had to terrorize Black freedmen back into their “place” because the one thing they had over them in the old South’s socioeconomic order, that they weren’t slaves, had been snatched away (and one swift look at the contemporary American political scene shows clear as day indications that they’re, essentially, STILL angry at that demotion in status); or French Algerians couldn’t stomach the idea of living in an independent Algeria where they would be on equal footing with Arab or Berber Algerians. So Protestant Ulstermen couldn’t tolerate being part of an independent state with these Catholic savages.”

But since we’re talking about the dangerous, delusional myths people need to believe, I might as well take this moment and take one tiny issue with one point in Dyson’s piece:

“This bigotocracy overlooks fundamental facts about slavery in this country: that blacks were stolen from their African homeland to toil for no wages in American dirt.”

People might not like me saying this, or at least think it’s the wrong time. Oh well… Of course African slaves were made “to toil for no wages in American dirt.” But they were not “stolen” from their African homeland; they were bought from other Africans.

Am I blaming the victim? No. But if that’s what it seems like, like a lot of people think I’m anti-semitically blaming the victim if I say that the idea that there’s only one God and everybody else’s is false, and on top of it that one God loves you more than anybody else, is bound to get you kinna disliked by those around you sooner or later, then that’s cool. (Another favorite idea of mine: if Christianity makes Jews so uncomfortable, they shouldn’t have invented it.)

I wrote my M.A. thesis in Latin American Studies on Cuba, particularly on abolition, and the complex interaction between the Cuban wars of independence from Spain, a vicious struggle that lasted three decades from 1868 to 1898 when the United States stepped in and annexed all of Spain’s remaining colonies, and the abolitionist struggle to end both the slave trade and slavery itself (the Spanish slave trade ended in 1868, and slavery itself wasn’t abolished, and then only gradually, until 1886). In brief, and with clear echoes in the American South, a creole class in Cuba was ambivalent about independence because they were afraid of being over-run by the Black Cuban majority, while a bourgeois pro-independence class didn’t think Cuba could be a democratic republic while so many Cubans were enslaved. In the end they did what most ex-slave societies did: free the salves and import indentured workers from the English-speaking Caribbean and immigrants from Galicia, marginalizing native Black Cubans, so that all groups together could be kept in a state of seasonal semi-employment which kept wages depressed and created enmity between the ethnic groups that should have felt some socioeconomic solidarity. Let’s not forget that the “Danza de los millones” — “the Dance of the Millions” — when sugar generated unprecedented wealth for Cuban planters, surpassing anything the nineteenth-century slave economy could produce, and made Cuba one of the richest countries in Latin America, when the beautiful Havana we now see was largely constructed — happened in the 1910s and 20s, decades after abolition.

My thesis involved a heavy dose from my advisor of reading in West African history. So any one who knows something about that history knows that almost none to absolutely none of the Africans brought to the Western Hemisphere during the slave trade — by some estimates 12 million human beings — were hunted down by slave-hunters Kunta-Kinte-style; it would have been logistically impossible to carry so many people across the Atlantic by that method. African slaves were bought in huge numbers, in en masse cargo-loads by European slave traders, from West African kingdoms who had enslaved them in the course of warfare between those kingdoms. There’s a legitimate argument to be made that the European slave trade made warfare between those kingdoms so profitable that conflict between West African states became endemic. Doesn’t absolve anybody though, not Africans, not Yankee do-gooders, who didn’t need slaves anymore because they had already gotten rich off the trade (as that great song from the musical “1776” points out: “Hail Boston! Hail Charleston! Who stinketh the most?” — see below) and could afford to get moral on the rest of us, not Protestants or Catholics or any Christians, or Muslims for that matter.

Here’s some other un-fun truths:

* Black slavery in the Muslim world never and nowhere reached the scale that it did in the Christian Western Hemisphere, but that may simply and largely be because the agro-industrial infrastructure was not present, not because Islam was more enlightened on the idea of slavery generally. East Africa supplied the Muslim eastern Mediterranean and Arabian peninsula with plentiful slaves for centuries. I don’t remember when the Ottomans abolished slavery, but I think it wasn’t even during the Tanzimat, but at some point in the 1908 constitutional revolution, i.e. early twentieth century. I’m always amused at “religion of peace” Islam apologists who try and make us understand how many passages there are in Muslim scripture that deal with the fair and “humane” way to conduct war, and massacre/execution or enslavement, and I wanna think: “gee, if there are so many passages that deal with the right or wrong way to conduct war, and massacre/execution or enslavement then those things must be mighty important to this religion of peace.”

NO monotheism is innocent; let’s get that through our heads once and for all.

* I hate to burst the bubble of Muhammad Ali or Malcolm X’s souls, or that of the wacked Nation of Islam, but Islam was not the religion of your African ancestors. (They may not have been called Cassius Clay, but it’s for sure that they weren’t called Muhammad Ali either.) Islam took a while to penetrate as far south as the coastal regions of West Africa. And actually, your ancestors almost certainly were the still polytheist inhabitants of the coast who might have been sold to European slave-traders by the newly Muslim kingdoms of the Sahel (currently Boko Haram country), the belt between the Sahara and the coastal jungle/savanna. If Afro-Americans anywhere in the Western Hemisphere are at all interested in the religion of their ancestors, they should look to Cuban Santería or Brazilian Candomblé or Haitian Voudon to re-establish a historical connection; when I was researching Santería in the 90s in Brooklyn, there was a real culture war between those Black Americans who were attracted to the Cuban religion of Yoruba origins — an amazingly relaxed, open-minded group, since polytheism is an open system, where you got to experience great music and dance, once you got past the practice’s defensive boundaries — and those Black Americans who were recent converts to Islam: puritanical pains-in-the-ass, like most converts, who had learned enough Arabic to call everybody else Kafirs, and who irritated the Senegalese and Malian immigrants in New York to no end.

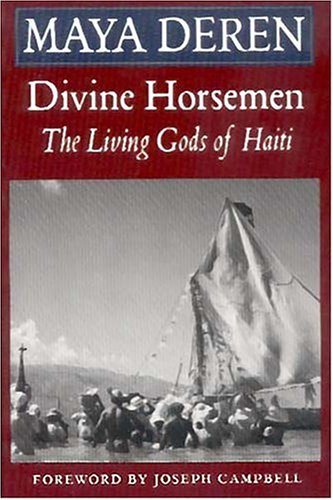

And Black Southern Baptist or Pentecostalist Christianity may have originally been the “slaveowner’s religion,” but its “getting the spirit” is a purely African phenomenon that has its emotional-devotional roots in the same parts of West Africa as Santería/Candomblé/Vodoun. Read the second to last chapter of James Baldwin‘s Go Tell it on the Mountain, which takes place in 1930s (I think) Harlem and then the last chapter of Maya Deren‘s Divine Horsemen on Haitian Vodoun. They mirror each other totally and both pieces still blow me away whenever I read them with the closest possible artistic representation of deity possession, the most impressive discursive capturing of a completely non-discursive, intangible experience, that I know of.

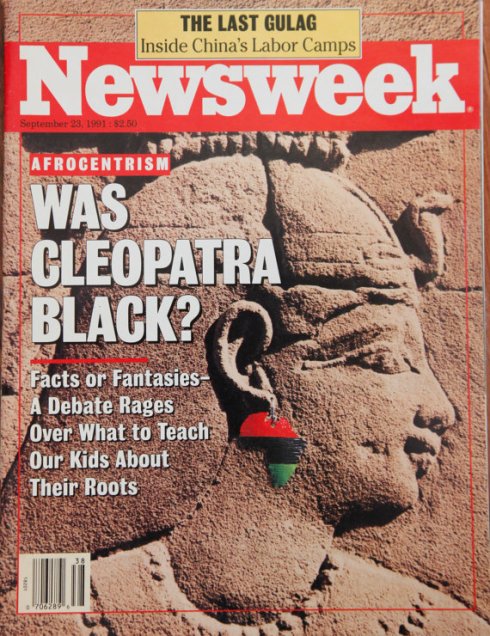

* Another bubble to burst is the “Kwaanza-ism” bubble. No African-American before President Obama had any connection to East Africa, Kenya, or Swahili. Another geographical term — Africa — turned into a completely artificial cultural construct, as if anything that happens on the African continent is somehow connected to African-Americans. The BBC is currently running a series on “The History of Africa” — so modest those folks over there — that, as had become common-place but I thought we had moved on from (turns out we haven’t), lumps together Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco into one “African” history instead of placing them in the history of the Greco-Roman-Christian-Arab-Muslim zone. (Does anyone remember the height of this absurd argument: the Newsweek magazine cover with the picture of an Egyptian relief and the screaming caption: “Was Cleopatra Black?” To Newsweek‘s credit, however, the article didn’t take its own title seriously and after going into an analysis of the African-American kulturkampf that gave rise to this question, ended simply with: “And Cleopatra? She was Greek.”)

And does anybody still celebrate Kwaanza?

I always chuckle when people call Constantinople the city on two continents, as if the quarter-mile crossing of the Bosporus into “Asia” is some kind of massive, marked civilizational change, like the people in Kadiköy are Chinese or something because it’s in “Asia.”

This was a real train-of-thought, free-association post — many think that everything I write is — so thanks for sticking with me. Below are some videos selections based on my continued free association process:

“Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

“Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

“Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop.”

“Strange Fruit” was written by Abel Meeropol, a real shayne Yid (beautiful Jew) if there ever was one. Read the NPR story on him that I’ve linked to. He also adopted the Rosenbergs‘ children, Robert and Michael, after that closetted scumbag Roy Cohn (a real self-hating Jew and queen if there ever was one) had their parents electrocuted.

Abel Meeropol watches as his sons, Robert and Michael, play with a train set. Courtesy of Robert and Michael Meeropol

Abel Meeropol watches as his sons, Robert and Michael, play with a train set. Courtesy of Robert and Michael Meeropol

And Maya Deren’s beautiful documentary footage of Haitian Vodoun:

See also Talking Heads’ David Byrne’s beautiful documentary, Ilé Aiyé on Bahian Candomblé. It’s the best introductory “text” I know. In reference to the dancing, drumming and singing, and animal sacrifice, food, alcohol and tobacco offerings that are meant to bring the god (or orisha in Yoruba) down into possession of his or her devotee, the narration includes the precious line: “They threw a party for the gods — and the gods came.”

And — on a lighter note — the great Celia Cruz below singing “Guantanamera” (you have to watch her move…wasn’t it great when women were allowed to have bodies like that? and if you have any idea what those silly kids who appear at the end are doing, please share) a song based on a poem of José Martí‘s, Cuba’s national poet and a man revered by Cubans of every color and political stripe anywhere. In the end, Black Cubans played a significant part in the Cuban struggle, personified most in the person of Antonio Maceo. As Celia sings: “Freedom was a trophy won for us by the mambí [largely Black guerilla fighters], with the words of Martí, and the machete of Maceo.” Yikes. The Cuban Wars of Independence were truly brutal, often really fought with machetes, the symbol of Afro-Cubans’ cane-cutting bondage become an instrument of rebellion, but Spain’s imperial ego simply did not want to let go of “la siempre fiel” — “the always loyal” — and extremely profitable island. 1898, the year Spain had to give in, was a year that became a byword for disaster for Spaniards, and Cuba was the most lamented loss; there’s still a common expression in Spain: “Más se perdió en Cuba” — “There was more lost in Cuba” — when you want to say that “oh well, things aren’t so bad, not, at least, compared to the loss of Cuba.” Ironically, Cuban independence was followed by a massive wave of migration to the island from Spain, largely from Galicia and Asturias, so in a weird way Cuba is the most connected to Spain of Latin American countries; a great, very unresearched musicological subject is the reciprocal exchange of musical influences from Cuba to southern Spain, especially for the gypsies of Seville and Cádiz, both port cities that were gateways to the Americas or “the Indies”, the flamenco genre “rumba” being just one indicator.

Celia was an initiated Santería priestess of the Yoruba male fertility deity Changó (you have to move a little in your seat every time you hear or say his name or you see lightning); her performances often contained dance moves associated with Changó (you have to move a little in your seat every time you hear or say his name); whether she was “mounted” by him at the time — which is the expression used to indicate deity possession, de allí Maya Deren’s reference to “horsemen” — is something only she can have known, though mostly devotees have no memory of their trance after they come out of it. Most salsa singers since have been initiates — have to stay competitive and you only can if the gods are helping you — and the improv vocabulary and dance gestures of salsa performances are heavily derived from Yoruba Santería. There’s one video of her singing “Quimbara” (below) where I think it’s really happening — the bending down and touching of the floor especially.

Here:

Finally, a NikoBakos memory. Mambí was a chain of 24-hour Cuban restaurants, Mambí #1, Mambí #2 — I think there were five of them all over once heavily Cuban Washington Heights and Inwood — that used to provide me and friends with some early morning, post-salsa sustenance. The food, like the neighborhoods, had become pretty Dominican by then, but they still made a mean Cuban sandwich. All the Cuban restaurants I knew as a kid in New York are now gone, in Manhattan and Brooklyn replaced by Dominican plantain places, and in Queens, by one more mediocre Colombian bakery. Schiller’s on Rivington Street still makes a good Cuban sandwich, but it’s $18.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

AC said…

If one wants to know what classical Arabic music is about, there’s no better example than this song “Al-Atlaal”. Thanks

Jewaira said…

Fanus Ramadan said…

“and alight searching for a wanderer” = “[you seduced me with] the saliva (from a kiss, a very common image in Arabic poetry) that the night-traveler (another common image) thirsts for”“The moments were embers” should be “The procrastination (or dallying or something) was embers”“Why are they still there etc.)”

=

“I haven’t kept her/them (either the beloved or the chains i’m not sure) nor have they spared me.” Ie the meaning is of having lost absolutely everything.“Ive had it with this prison etc.” “How much more (ila ma) captivity, when the world is before us?”“Sure footed walking like a king” king should be “angel”breeze of valleys should be breeze of the hills.

Chris said…

Twosret said…

Op! said…

1. the poem itself (original) differs – albeit slightly – from the lyrics as she sings them

2. Some punctuations are altered giving a completely different meaning to the original poem – hence, you lose the real meaning of the poem.I am happy to point those out or to even provide you with an alternative translation “with an explanation” if you would like.. Just let me know.

Anonymous said…

barbender said…

umelbanat said…

Itje Chodidjah said…

Itje Chodidjah said…