The most recent picture of my grandmother to resurface, with my father as a baby, she in somewhat less then the full-out finery of the photo at bottom with my grandfather included, but with her good sash and her mecidiyia around her neck and forehead in any case.

The most recent picture of my grandmother to resurface, with my father as a baby, she in somewhat less then the full-out finery of the photo at bottom with my grandfather included, but with her good sash and her mecidiyia around her neck and forehead in any case.

Probably the saddest of all the stories I got bombarded with while in Derviçani this time was one told to me by my cousin Chrysanthe, shown here in this picture with the Coke can (below) with her daughter Amalia and her two grandsons, cracking Easter eggs at the Monastery above the village on Easter Monday where the dancing takes place. (See “Easter in Derviçani” — the stunning young girl behind them is my niece Marina — click)

As our house was pretty much just off the village’s main square, most of the afternoons my grandmother could be found sitting on the stone bench in front of the house watching people. Try to imagine her about forty years after the above photo was taken, but not quite as old yet as this last one we have of her. (click)

As our house was pretty much just off the village’s main square, most of the afternoons my grandmother could be found sitting on the stone bench in front of the house watching people. Try to imagine her about forty years after the above photo was taken, but not quite as old yet as this last one we have of her. (click)

Our house today (click). Built by my grandfather with blood and sweat shed in the slaughterhouses of Buenos Aires. The village collective confiscated it and allowed my grandmother to live in only one room, keeping hay and seed and agricultural implements in the other three odas. It’s lain abandoned since her death. But someone always burns a cross on the top of the doorway at Easter. This year I got to do it myself.

Our house today (click). Built by my grandfather with blood and sweat shed in the slaughterhouses of Buenos Aires. The village collective confiscated it and allowed my grandmother to live in only one room, keeping hay and seed and agricultural implements in the other three odas. It’s lain abandoned since her death. But someone always burns a cross on the top of the doorway at Easter. This year I got to do it myself.

My grandfather dead in some prison camp in central Albania, my father, the only child, in America, letters getting through the censors only every so often, she was lonely, despite the hordes of family she had to take care of her. People say she would beg to hold any baby that someone brought by: “I just want a baby to wet me,” she would say, “and let it be someone else’s.”

But around Easter my cousin Chrysanthe says: “She would tell us quietly to come inside, and she would open up a little sentouki [chest] she had with a pile of bright red Easter eggs inside.” This was in the mid-sixties, when Albania, recently aligned with a China in the midst of its brilliant Cultural Revolution, had prohibited any form of religion whatsoever and dyeing Easter eggs could land you in jail, even the parents of the child, in this case, if they knew and hadn’t reported it. “And I would say, ‘oooooyyyyyy Kako [auntie]*, can I take one?’ and she’d say, ‘No canım, we’re just going to keep them here and you’ll come and we’ll look at them and we’ll play with them and have fun and then we’ll put them back in the sentouki and you won’t tell anyone, ok?’”

This is what those systems wasted their energies on, in case you’re wondering how it is that they collapsed like a house of cards from one day to the next after destroying the lives of millions: forcing old women to dye eggs in secret. No one ever knew where she got the dye from or how she even got so many eggs together at one time. She probably denied herself the product of the chickens she was allowed to keep to have enough eggs for Easter. Soon after, they prohibited private poultry and confiscated bostania too (kitchen gardens), even if they were part of your house’s immediate property, and all food items had to be gotten from the village collective, but I think some local Party member with half a soul let her and a few other old people keep theirs.

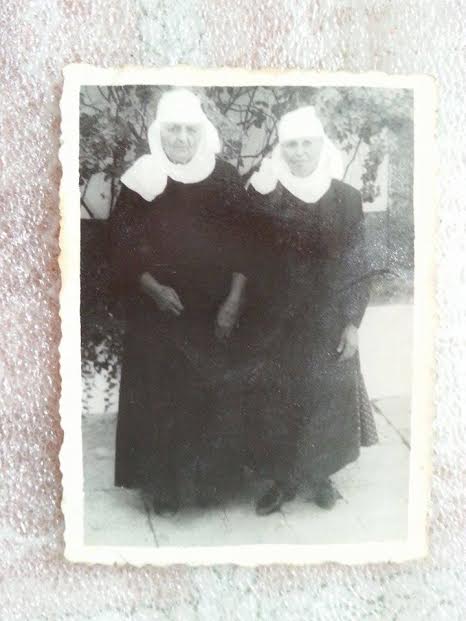

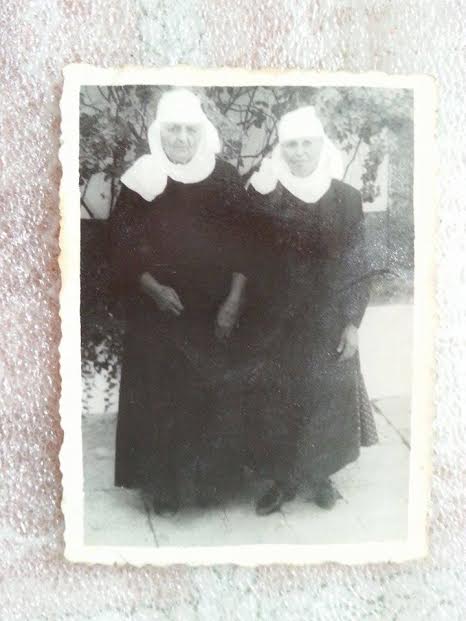

There’s a partly satisfying coda to this story though. Below is my grandmother, Martha (Mantho) with her favorite sister Alexandra (Leço).

Their maiden name was Çames — and you can deduce for yourself what it might mean that Çam is also one of the major tribal sub-groups of southern Albanians, the ones who lived in what’s now Greek Epiros and who were violently driven out by Greek nationalist forces during WWII for supposedly collaborating with the Germans. Their father, my great-grandfather GianneÇames** came to the United States in 1895 and opened a fruit store in Mystic, Connecticut (the willingness of these men to just up and go off to places that must have been to them the equivalent of Zambia to us has always astounded me). A few years later, he brought three of his sons over, my grandmother’s brothers, and during the summers he used to send them down to Watch Hill, Rhode Island, a very understated, high-WASP resort on the far western shore of the state, to sell popcorn and cotton candy on the beach. But from these modest beginnings they eventually opened the Olympia Tea Room in 1916, which is still there and was quite the poshest place to eat in town for decades — and has suddenly become re-hip again. For better or worse, you know I’ve taken you seriously as a friend when I’ve dragged you down to Watch Hill to make you pay homage, as if it were my village; for my father, cut off from his own for most of his life, it was. So the Çamedes ended up being people of some consequence in Derviçani; to have been given a Massios daughter as a bride, my great-grandmother Kostando (those who know will know what I mean), you have to have been, and their house was not just a prosperous one, but one always open to all, the “peliauri” – courtyard – where my father grew up, always swarming with women and children and guests and the whole mahalla coming in and out all day.

Their maiden name was Çames — and you can deduce for yourself what it might mean that Çam is also one of the major tribal sub-groups of southern Albanians, the ones who lived in what’s now Greek Epiros and who were violently driven out by Greek nationalist forces during WWII for supposedly collaborating with the Germans. Their father, my great-grandfather GianneÇames** came to the United States in 1895 and opened a fruit store in Mystic, Connecticut (the willingness of these men to just up and go off to places that must have been to them the equivalent of Zambia to us has always astounded me). A few years later, he brought three of his sons over, my grandmother’s brothers, and during the summers he used to send them down to Watch Hill, Rhode Island, a very understated, high-WASP resort on the far western shore of the state, to sell popcorn and cotton candy on the beach. But from these modest beginnings they eventually opened the Olympia Tea Room in 1916, which is still there and was quite the poshest place to eat in town for decades — and has suddenly become re-hip again. For better or worse, you know I’ve taken you seriously as a friend when I’ve dragged you down to Watch Hill to make you pay homage, as if it were my village; for my father, cut off from his own for most of his life, it was. So the Çamedes ended up being people of some consequence in Derviçani; to have been given a Massios daughter as a bride, my great-grandmother Kostando (those who know will know what I mean), you have to have been, and their house was not just a prosperous one, but one always open to all, the “peliauri” – courtyard – where my father grew up, always swarming with women and children and guests and the whole mahalla coming in and out all day.

The Olympia Tea Room, “est. 1916,” Watch Hill, Rhode Island and general view of the town’s harbor below (click on both — I don’t know who took this Olympia photo but it’s great — thank you).

The Olympia Tea Room, “est. 1916,” Watch Hill, Rhode Island and general view of the town’s harbor below (click on both — I don’t know who took this Olympia photo but it’s great — thank you).

Yet my great-grandfather Gianne married off his two favorite daughters to two men without much wealth or property, my grandfather NikoBakos and my great-uncle MihoBarutas (Michales). And I think it was on their sheer reputation as outspoken men to be respected and feared – and in our parts, even today, you still have to be both – or, as men period, that he did so; my grandfather was tall and handsome but not to be messed with – “his word was law through all the villages of Dropoli” – I was told on this trip,*** and the Barutaioi are proverbially unafraid of anyone or anything. Ex-Ottomans will know that the name itself means “gunpowder,” and that’s all you need to know.

Yet my great-grandfather Gianne married off his two favorite daughters to two men without much wealth or property, my grandfather NikoBakos and my great-uncle MihoBarutas (Michales). And I think it was on their sheer reputation as outspoken men to be respected and feared – and in our parts, even today, you still have to be both – or, as men period, that he did so; my grandfather was tall and handsome but not to be messed with – “his word was law through all the villages of Dropoli” – I was told on this trip,*** and the Barutaioi are proverbially unafraid of anyone or anything. Ex-Ottomans will know that the name itself means “gunpowder,” and that’s all you need to know.

My great-aunt, Kako Leço (above) and my great-uncle Lalo Miho Barutas. I wish we had a picture of them younger but no one can seem to locate one. (click)

My great-aunt, Kako Leço (above) and my great-uncle Lalo Miho Barutas. I wish we had a picture of them younger but no one can seem to locate one. (click)

(My grandparents and my father in what I suppose must have been around 1931 or ’32. If you look carefully you can see that the photo is a Photoshop job of its day; my grandfather was photographed in Buenos Aires and the photograph later attached in Albania; it’s always been a metaphor of an inheritance of absent fathers for me. My grandfather was known as Djoumerka, a high mountain range in southern Epiros because he was so tall (but see more on that below). My grandmother’s outfit in this picture — all made possible by rich WASPs in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, early globalisation — was described to me once by a woman, my Theia Vantho, whose memory I would never dare to doubt: the vest and sash were a maroon-purplish velvet embroidered with gold thread, which would have looked most like this kind of work, but with a deepr, more puplish hue:

(My grandparents and my father in what I suppose must have been around 1931 or ’32. If you look carefully you can see that the photo is a Photoshop job of its day; my grandfather was photographed in Buenos Aires and the photograph later attached in Albania; it’s always been a metaphor of an inheritance of absent fathers for me. My grandfather was known as Djoumerka, a high mountain range in southern Epiros because he was so tall (but see more on that below). My grandmother’s outfit in this picture — all made possible by rich WASPs in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, early globalisation — was described to me once by a woman, my Theia Vantho, whose memory I would never dare to doubt: the vest and sash were a maroon-purplish velvet embroidered with gold thread, which would have looked most like this kind of work, but with a deepr, more puplish hue:

(click)

The apron, green silk with heavy multi-coloured embroidery, the outer, mid-hip length vest, what was known as the “şita,” barely visible at the sides and mostly decorated to be seen from behind, was white woolen felt, trimmed in red and black. The medallions embroidered on either side of the vest were not traditional and generally it was seen at the time as hubristically opulent, so much so that the kind of mean tongues that flourish in small communities like this attributed the misfortunes of her later life to her excessive pride as a young woman. Click, double if you wanna see the details.)

Of course these are not qualities that get you far in a totalitarian regime like Hoxha’s Albania, except blacklisted, sent to jail or into internal exile or killed. And that’s what happened to them. Both branches of the family and by association the whole network of related clans suffered greatly during communist rule and yet held together. The Çames gene is a strong one, and anyone who is from a big family knows how certain emotional “affinities” – in this case the love between the two sisters – end up being transmitted down specific threads through generational lines: my Kako Leço’s son, Vangeli, a first cousin of my father’s who my father barely knew, is my favorite uncle in the village: the Baruta patriarch now, he’s also a man to be respected and feared, who started from less than zero when the communist regime fell apart and is now a highly successful entrepreneur with a business that reaches Albania-wide markets. His daughters — especially one in Tirane, Calliope (she’s shown in the passing of the Light photo in “Easter in Derviçani,“) — are my favorite cousins, and one of Calliope’s sons, also Vangeli, named after his grandfather, and destined to be an equally formidable personality, is my favorite nephew.

My Uncle Vangeli spoke his mind as much as one could all during communist times and how he escaped harsher punishment during those decades is a miracle of sorts. But underneath the fear of the Party, older fears and structures of respect were still operating, I think, and that’s what saved them. One of the village informers, the usual squirrels in those systems who will tell on others for an extra ration of food — what in the Soviet Union was known as a stukach in Russian, a “knocker,” i.e., someone who comes and knocks at night to tell his superiors the information they want to know, or a sapo, a toad, in Latin America, another continent blessed with the necessary abundance of totalitarian experiences to develop such terminologies – had the misfortune of living next door to my uncle, and he would try to threaten them occasionally, but my uncle was unafraid of even getting into fistfights with him when necessary, so nothing ever came of it.

And back to Easter eggs. By ’88 or ’89 things had started, like all over Eastern Europe, not so much to relax, but to show such obvious signs of cracking apart that, as my relatives put it, “the fear started lifting.” The Barutaioi started dyeing their own eggs during Holy Week, though there was still no functioning church or any open observation or acknowledgment of the holiday. But on Easter night, after the Resurrection, when they had cracked and eaten their eggs, they would take the shells and throw them over the wall into the Party snitch’s front courtyard… Forget empty tombs and angels in white and “Τι ζητείτε;”**** How’s that for some “good news” on Easter morning? And being a Jungian believer that no symbolism is accidental, I can see the cracked red shells in my mind, like splatters of the blood this guy had on his hands — though this is a person obviously too much of a hayvani to have been affected much I imagine. For to be a Christian in a village like Derviçani, and have people throw Easter egg shells at you on Easter Sunday, and not immediately find a bridge to jump off of, or a quiet corner to blow your brains out, you have to have a fairly huge hole where your conscience or any sense of shame should be. He’s still around. They’re still neighbors. And my Uncle Vangeli smiles and greets him courteously on the evening passegiata in the village square.

And my grandmother’s hidden eggs have been vindicated.

–

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

*”Kako”– aunt, and “Lalo” — uncle, are two of some of the Albanian words we use in our villages, though most people today just say “theia” or “theio” in Greek. I’m the only one who still says Kako and Lalo and they all get a big kick out of it. Ismail Kadare has a hilarious character named Kako Pino in his book about his native Gjirokaster, “Chronicle in Stone” so I don’t know if it’s maybe a local usage only, or only a Tosk word (the southern ethnic/linguistic division of Albanians) because my nephew Vangeli in Tirane uses the Turkish “teyze” when he talks to his aunts.

** This is how we say (or again, said…) our names in the region: the first name, undeclined, attached as a prefix to the family name. This is probably a left over from the day when there were no family names and only Muslim-type patronymics were used: your name and your father’s attached after. So instead of “NikoBakos” I would have been “NikoFotos.” Thus the oldest historical ancestor in my mother’s family, the Giotopoulos, was GioteStauros — his father Stauros is almost a sort of mythical character lost in time — and after GioteStauros, the family started calling themselves Giotopoulos, “son of Giotes.” Women in this heavily gendered world were never known by their first names outside their immediate households, but by their husband’s name with a female suffix attached; thus my grandmother was “NikoBakaina” or even the more Slavic “NikoBakova.”

***My grandfather, it’s turned out, was quite the guy. Absolutely fearless in a way hard for us to comprehend, he was a kind of village rowdy as a kid (the guys of Derviçani are known as such even today and their arrival in the cafés of neighboring villages in the evenings is said to be slightly unwelcome because it often means trouble; apparently they drink a hefty amount so they spend a lot of money and that’s good, but the local girls like them and that combination doesn’t always end well.) And he would even engage in some occasional sheep rustling with a buddy of his — not for the material gain, but because it was a kind of male rite of passage in the region, as it was till recently in parts of Crete (see Michael Herzfeld’s “The Poetics of Manhood: Contest and Identity in a Cretan Mountain Village” — below; let’s not mistake this with resistance to Ottoman or Muslim hegemony, as people love to do with the banditry traditions of the Balkans; it was pure thievery). But if there were some lira to be made in the process, that was no problem either. His nickname Djumerka, may not have come from just how tall he was, but from the fact that under the hire of a certian Ismail Ağa from Argyrocastro (Gjirokaster), he and a buddy of his (this buddy’s grandson remembered the ağa‘s name) went down to the Djumerka mountains when they were teens and stole the flocks of another rich Turk, an enemy of Ismail’s, from those parts and brought them back to Gjirokaster for him. Given the chaos of late Ottoman times in the Balkans, this is not entirely the superhuman feat we may imagine it to be, not in terms of law enforcement at least, but we’re talking a great distance of extremely rough, high terrain and it was impressive enough to have entered the village’s legend canon. Then he up and went to Buenos Aires in his early twenties and worked in the slaughterhouses there; Argentina is on my list of “to go” places partly or mainly because of that; I would give anything to find out even the tiniest detail of what his life there was like. And then when he came back, with no more than an elementary school education, I think, and his pure charisma, he was important among the leaders of the the delegation from the Greek-speaking villages of Dropoli to the King, Zog, in Tirane, to protest the closing of their Greek-language schools. The campaign was successful. Elementary school education in Greek resumed and he soon after went to jail for the first of many times.

In the late 1950’s is when he went to jail for good and never came out and all we know is that he was buried in a mass grave somewhere in central Albania. People in the village talk a lot about who snitched under custody on those occasions; neighbors and relatives were often taken together, so everyone would eventually find out. If you could live with yourself afterwards, you could give false testimony about someone else and get off easier or be released or maybe just get the beatings to stop. I turned it into a ritual questioning this time when I was there, of anyone I could, because I had to know: “Lalo, my grandfather never gave false witness against anybody to save his hide, did he? No. Lalo, my grandfather never…? No. Lalo…? No.” When I got the third “No” from my Uncle Vangeli this time I was satisfied.

This is all hard stuff to live up to. When they’re thrilled to have NikoBako come to Derviçani, I’m actually ashamed, because they really see him. I’m just a cipher — a proud one, yes, but just a representative of someone I could never be. Half of the time, with all my family on both sides, I’m living off of credit from my mother’s kindnesss and generosity and half the time off of my grandfather’s toughness and bravery and my father’s stoic bearing of the torch. If you think it’s great to come from this kind of stock and have these kinds of tales to tell, think again.

**** “Τι ζητείται τον ζώντα μετά των νεκρών; Τι θρηνείτε τον άφθαρτον ως εν φθορά;” — “Why do you seek the Living among the dead? Why do you lament the Incorruptible amidst the rot?” the angel asks the women who come to the grave on the day of the Resurrection, is my favorite verse of the Easter Canon.

Note: For those of you who made it this far with me on this post, thank you. I hope it wasn’t boring or embarrassingly personal. I thought a lot about whether I would ever get so deep into this stuff on this blog and decided to just go ahead.

Addendum: For the person who asked how my father can have been an only child and I can have all these hundreds of aunts and uncles and cousins and nieces and nephews, that’s because in Greek every indirect relative of an older generation is my aunt or uncle (even if he’s not my parent’s sibling but third or fourth cousin), and anyone of my generation laterally is a cousin and any children of those cousins, who may be third or fourth or fifth cousins, who are of a younger cohort, are my nieces and nephews. My father was an only child; but my grandmother one of eight. So out of those eight branches come this plethora of kin.

–

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

Tags: "Τι ζητείται τον ζώντα μετά των νεκρών; Τι θρηνείτε τον άφθαρτον ως εν φθορά;", Albania, Çames, Çams, Bakos, Barutas, China, communism, Crete, Cultural Revolution, Derviçani, Djumerka, Dropoli, Easter, Easter Canon, Easter eggs, Enver Hoxha, Epiros, Gheg, Greek schools of Dropoli, Maoism, Massios, NikoBakos, sapo, sheep rustling, Soviet Union, Stalinism, stukach, Tosk, Watch Hill Rhode Island