…full of the pain they don’t know and the humor they’re lacking…

The New Yorker last week published a story of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s: “Job“–to anyone who wants to read it because they haven’t hidden it from non-subscribers. Mostly I want to dedicate it to the Messenger and his parea. It’s a tale told to Singer by someone — I dunno if it’s a fictive character or not — in the 1970s. It was written by Singer at the time, but was not translated from Yiddish to English until March-July, 2012 by David Stromberg. Much like Vassily Grossman’s Life and Fate (which I touch on briefly here), it deals with the suffering of a twentieth-century Jewish everyman, sandwiched between the nightmare of Nazism and Stalinism, with bitter, caustic humor completely intact (which Grossman couldn’t really do).

Why do I dedicate this to the Messenger?

Because I remember distinctly in one late-night email battle-session, when he wrote me: “And why is it so wrong for bourgeois guys — like the both of us [his emphasis] — to have an ideology or an ideological schema?” It’s a slightly tricky question to be asked in Greek and to have to answer from a Greek-speaker but native English-speaker’s perspective, because the word “αστικό” in Greek means urban and urbane and bourgeois, in its socio-political sense, all at once, so it’s difficult to separate. But I quickly clarified the difference between my ethnic-American, working-class New York borough background and his petit bourgeois Athenian upbringing. And yet I couldn’t put into words — or rather — couldn’t, at the time, find an example or definition to support the difference I was trying to establish.

But we can sort of close in on what I meant… Someone — Simone Weil, Kafka, Solzhenitsyn, Rebecca West, Walter Benjamin, the great Hitchens, historian Timothy Snyder…I’m embarrassed that I can’t remember — said: “The twentieth century is when ordinary people realized that bookish young men who read big books full of big ideas could have a total and devastating effect on their lives.”

Or in the words of Singer’s Job: “Our young little Stalinists, the onetime yeshiva boys and simple idlers, hounded me to the point that I started longing to go back to Russia.”

And that’s where it lays. It’s Singer’s Job that makes the knock-out realization:

“I’ve realized one thing: the worst people are those who want to save the world. Among simple folk—merchants, skilled workers, the so-called little man—one can still find decent people. But among those who want to bring about the coming of the Red Messiah there is no truth, no compassion. What’s easier than torturing in the name of an ideal?”

Of course your messianic vision doesn’t have to be Red; the Messenger’s is vehemently non-Red. But that’s one thing that he never understood. That that hue doesn’t matter. That after a certain point he — he and his nationalism and his cronies’ nationalism — became the enemy for me. The “worst people” are the ideologues. After liberating him from the petit bourgeois prejudices he had been raised with, and becoming a model of “Roman-ness” for him, I didn’t realize that I had created a Frankenstein. And he has never realized that he’s the enemy to me. The people who tortured innocent women in our family like our aunt A. and killed heroic young men like our uncle S. and others, who looted and burnt down my mother’s paternal home, who imprisoned and persecuted and exiled my maternal uncle L. for decades, the people who tormented my father and his family and his extended clan for decades, who threw my grandfather into a prison camp in Albania and then into a mass grave somewhere, who isolated my grandmother in one room of the house her husband had built for her, who separated her forever from her only child, who created the pall of depression and unspoken sadness that hung over my family all my life… Those people weren’t Albanians to me. Or Muslims or communists or fascists or Turks or anything else or anyone else that the Messenger loves to hate. They were petty little ideologues like him: bookish nerds who feel empowered by imposing their ideological hard-ons on innocent people, and making them suffer intolerable suffering in the name of their grand ideological vision. “What’s easier than torturing in the name of an ideal?” He’s the enemy. But he doesn’t get it. Y de allí his shock when I lay into him.

The other money quote from the Singer story:

“…I’d arrived at a certain philosophy: We can’t live openly in this world. We have to smuggle ourselves through. People, like animals, must constantly hide themselves. If the enemy’s on the right, you go left. It goes left, you crawl right. This very philosophy—you can call it cowardice, it doesn’t bother me—has helped me. I knew where the informers were and I avoided them. A lot of leftists—half-leftists and converted leftists, so to speak—went to Vilna or Kovno, but I went on to Russia, not to the big cities but to little towns, villages, collective farms. There I found a different kind of Russian: generous, ready to help. There they laughed at communism.”

Laugh at these people. Russians’ and especially Jews’ saving strength. That’s all there is to do. Until they knock on your door.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

My grandmother (click)

My grandmother (click)

And the whole article, since The New Yorker is being so unusually generous about it:

August 13, 2012

Job

By Isaac Bashevis Singer

Translated by David Stromberg

Editors’ Note: This story, by Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902-1991), was first published in Yiddish in 1970, and is appearing here in English translation for the first time. (See the translator’s note below about how it came to light.) Singer published more than sixty stories in The New Yorker, beginning in 1967; we’re grateful for this chance to present his work once again.

****

Being a writer for a Yiddish newspaper means wasting half the workday on people who come to request advice or simply to argue. The manager, Mr. Raskin, tried several times to bring this custom to an end but failed repeatedly. Readers had each time broken in by force. Others warned that they would picket the editorial office. Hundreds of protest letters arrived in the mail.

In one case, the person in question didn’t even knock. He threw open the door and before me I saw a tiny man wearing a black coat that was too long and too wide, a pair of loose-hanging gray pants that seemed ready to fall off at any moment, a shirt with an open collar and no tie, and a small black spot-stained hat poised high over his brow. Patches of black and white hair sprouted over his sunken cheeks, crawling all the way down to the bottom of his neck. His protruding eyes—a mixture of brown and yellow—looked at me with open mockery. He spoke with the singsong of Torah study:

“Just like this? Without a beard? With bared head? Considering your scribbling, I thought that you sit here covered in prayer shawl and phylacteries like the Vilna Gaon—forgive the comparison—and that between each sentence you immerse yourself in a ritual bath. Oh, I know, I know, for you little writers religion is just a fashion. One has to give the ignorant readers what they truly desire.”

A wise guy, I thought. Aloud I said, “Please, sit down.”

“And what good will it do me to sit? Let me first get a good look at you. Right here is where you write? Right here, next to this little table, is where the goods are fabricated? This is where your holy spirit, so to speak, makes its appearance? Well, it is what it is. And, anyway, how do people write all these lies? With simple pen and ink. Paper is patient. You can even write that there’s a festival in Heaven.”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“My name is Koppel Stein, but you can call me Job, because I’ve suffered as much as Job, and possibly even a little more. Job had three friends who came to console him, and in the end God took it upon Himself to offer a word of comfort. Then He repaid him twice over: more donkeys, prettier daughters, and who knows what else. I haven’t been comforted by anyone, and the Almighty remains silent, as if nothing had happened. I’m Job squared, if one can put it this way. Do you have a match? I’ve forgotten my matches.”

I went out and brought him matches. He lit a cigarette and blew the smoke right in my face.

“Forgive me for speaking to you this way,” he continued. “As they say, it’s my troubles speaking. You know it down to the last letter: ‘blame not a man in his hour of sorrow.’ The other day you complained in your write-up about a reader who’d held you up for six straight hours. I’ll keep it short, though how can one shorten a story that’s already lasted more than forty years? I’ll give you just the bare facts and if you’re no fool it’ll be as they say: ‘a word to the wise is enough.’ I’m one of those crazy people—this, it seems, is what you called them—who want to save the world, to institute justice, and other things of that kind.

“With me it started when I was still a little kid. Our neighbor Tevel the Shoemaker worked straight from the first rays of the sun until late into the night. In the winter I heard him banging on nails when it was still dark outside. He lived in a tiny room. He had everything there: the kitchen, the bedroom, the workshop. That was where his wife, Necha, gave birth every nine or ten months, and there the infants died. My father wasn’t much richer. He was a teacher. We also lived in a single room and had so little to eat that we might as well have deposited our teeth in the bank.

“Early on I began to ask: how is this possible? My father answered that this was God’s will. And I came to despise—with a thorough hate—the very same God Almighty who sat eternally in his seventh heaven, showered with respect and greatness, while his creatures suffered and died. I won’t get into details—I know from your work that you’re familiar with these details and even with the so-called psychology of such things.

“In short, I was about fifteen when I went astray. We had a political group in town where we read Karl Marx and Karl Kautsky and even got our hands on a brochure by Lenin—in Russian, not in Yiddish. In 1917, when the Revolution broke out, I was a Russian conscript. I managed to catch some lead near Przemysl and was laid up in a military hospital. What I went through in the barracks and on the front you probably know yourself. No, you know nothing, because my greatest sorrows came from my own mouth. I told everyone the truth. I spoke against the officers. To this day I don’t understand why they didn’t have me court-martialled and shot. They must have needed cannon fodder.

“Kerensky called for further fighting and I became a Bolshevik. I ended up in Poltava, and there we went through the October Revolution. Mobs set upon us and we were chased away. Who wasn’t there? Denikin, Petliura, others. I was eventually wounded and discharged from the Red Army. I got stuck in a little town where there was a pogrom against the Jews. With my own eyes I saw how they slaughtered children. I lay in the hospital and got gangrene in one foot. I’ll never understand why, out of everyone, I came out alive. Around me people died from typhoid fever and all kinds of other diseases. For me, death was an everyday thing. But despite all this my faith in man’s progress became stronger, not weaker. Who started wars? Capitalists. Who incited pogroms? Also they. I’d seen plenty of wickedness, stupidity, and pettiness among my own comrades, but I answered myself ten times a day with the same refrain: we are products of the capitalist system. Socialism will produce a new man—and so on and so forth. Meanwhile, my parents died in Poland, my father from hunger and my mother from typhoid fever. Though possibly also from hunger.

“After the mobs were driven out and things subsided into some kind of order, so to speak, I decided to become a laborer, despite the fact that I could have taken a government post or even become a commissar. By that time I was already in Moscow. I’d studied carpentry in our little town, so I entered a furniture factory. Lenin was still alive. For the masses, the big holiday still held sway. Even the New Economic Policy didn’t disappoint us. How do the Hassidim put it? ‘Descent for the sake of ascent.’ To stand and hear Lenin speak was a compensation for all the suffering and humiliation. Yes, suffering and humiliation. Because in the factory where I worked they cursed me and called me a ‘dirty Yid’ and mocked me no less than they had in the barracks.

“I was constantly hounded—and by whom? Party members, fellow-workers, Communists. They took every chance to tell me to go to Palestine. Of course, I could have complained. You heard of cases in which workers were put behind bars for anti-Semitic acts. But I soon realized that these were not isolated incidents. The entire factory was saturated with hatred for Jews—and not only Jews. A Tartar was no less inferior than a Jew, and when the Russians felt like it they made mincemeat of Ukrainians, Belarusians, Poles. Try sweeping away a trash can. I saw with sorrow that the Revolution had not changed all the drunkenness, debauchery, intrigues, theft, sabotage. A doubt stole into my heart, but I kept it silent with all my powers. After all, this was still just the beginning.

“I promised you to be short and this is what I’ll do. Lenin died. Stalin took over. Then came the plot against Trotsky—who for me was a god. Suddenly I heard he was nothing but a spy, a lackey of Pilsudski’s, Leon Blum’s, McDonald’s, Rockefeller’s. There are hearts that burst from the least worries, and there are also hearts as solid as a rock. It seems I have a stone there on my left side. What I’ve put up with, I only wish upon Hitler, if it’s true that he’s still alive somewhere, and that someone is hiding him in Spain or Argentina. I shared a room—actually a cell—with two other workers: drunks and scoundrels. The language they used—the smut! They stole from my pockets. At the factory, they called me Trotsky more than once and pronounced the ‘r’ with a Yiddish accent. Then came the arrests and the purges. People I knew—idealists—were taken away to prison and either got sent off to Siberia or rotted in jail. I began to realize, to my horror, that Trotsky was right: the Revolution had been betrayed.

“But what is a person to do concretely? Could Russia endure a new revolution, or even a permanent revolution? Can a sick body stand one operation after another? As my mother, peace be upon her, used to say: If a dog licked my blood, it would poison itself….

“So the years passed. Permanent revolution is impossible, but there is such a thing as permanent despair. I went to sleep in despair and awoke in despair. I was drained of all hope. Yet Trotskyist circles sprang up regardless of the persecution. The old conspiracies from the Tsarist times repeated themselves. The Revolution had fallen with a thud, but humankind doesn’t resign itself. This is its misfortune.”

II

“In 1928, I came back to Poland. So to speak. I smuggled myself across the border, helped by my fellow-Trotskyists. Each step involved the worst of dangers. I forgot to tell you that while still in Russia I’d been held at Lubyanka for seven months precisely under the suspicion that I was a Trotskyist. There wasn’t a single night in which I wasn’t beaten. Do you see this crippled fingernail? This is where a Chekist stuck a glowing rod into me. I had my teeth knocked out and those who did it were my fellow-proletarians, a curse upon humankind. What was done in prison can’t be put into words. People were physically and spiritually degraded. The stench of piss pots made you crazy. In a prison you can find all sorts of people. There was homosexuality as well as outright rape. Yes, be that all as it may, I smuggled myself into Poland and came to Nieswiez—perhaps you’ve heard of this little town? As soon as I crossed the border, the Poles arrested me. They later let me out, but then I was put behind bars again.

“This was in 1930. I’d been given a contact among the Trotskyists in Warsaw, but they ended up being just a few poor youths, workers. The Stalinists considered it a good deed to denounce Trotskyists to the authorities, and most of them were imprisoned in Pawiak or Wronki—a terrible prison. In Warsaw, I tried to tell them about what was going on in Russia, and don’t ask what I had to put up with! Our young little Stalinists, the onetime yeshiva boys and simple idlers, hounded me to the point that I started longing to go back to Russia. I was beaten, spat on, and called nothing but a renegade, fascist, traitor. A few times I tried to speak to an audience, but thugs from Krochmalna Street and Smocza Street came to shut me up. Once, I was stabbed with a knife. There is no worse lowlife than a Jewish Chekist, Yevsektsia member, or plain Communist. They spit on the truth. They’re ready to kill and torture over the least suspicion. I already understood that there was no difference between Communists and Nazis, but I still believed that Trotskyism was better. Something had to be good! Not everyone could be evil.

“Up until now I haven’t mentioned my personal life, because in Russia I hadn’t had any personal life. Even if I could have sinned, there was nowhere it could be done. With several men living in a single room, you’d have to be an exhibitionist. I witnessed both sexes in their utmost shame and misery, and I, as they say, lost my appetite. Hundreds of thousands of illegitimate children were brought forth—the homeless—who in turn became Russia’s curse and peril. When a woman went to buy bread, they fell upon her and stole it from her. Very often they raped her too. There was no lack of downright thieves, murderers, drunks. The Revolution should’ve brought an end to prostitution, but whores loitered all around the very Kremlin. In Warsaw, I met a Trotskyist woman. She was hunchbacked, but for me a physical defect was no defect at all. She was clever, intelligent, idealistic. She had a pair of black eyes and from them all the sadness and wisdom of the world peered out—though where in the world is there wisdom? We became close. Neither of us thought much of the idea of going to a rabbi. We rented an attic room on Smocza Street, where we started living together. That’s also where we had our daughter, Rosa—naturally, after Rosa Luxemburg.

“My wife, Sonia, was a nurse by trade—a medic and a compassionate caregiver. She spent her nights with the ill. We seldom had a night together. I couldn’t find any work in the Polish factories and earned a little by repairing poor people’s furniture—a closet, a table, a bed. I earned peanuts. As long as there wasn’t any child, it was still bearable. But when Sonia was in her later months it became difficult. In the middle of all this I was arrested. I’d been denounced by my Jewish and proletarian brothers, who’d invented a false accusation against me and actually planted illicit literature. What do you know about what people are capable of doing? Some of them later fell in Spain—they were killed by their own comrades. Others perished in the purges or simply in Comrade Stalin’s labor camps.

“The entire trial against me was a wild invention. Everyone knew this: the investigator, the prosecutor, the judge. They put me together with people whose faces I’d never seen and said that we’d planned a conspiracy against the Polish Republic. The policemen—guardians of the law —gave false testimony and swore to lies. In prison, the Stalinists hounded me so much that each day was hell. They didn’t take me into their circle. Among the civilians there were rich people, especially women, who brought political prisoners food, cigarettes, other such things. They even provided lawyers free of charge. But since I didn’t believe in Comrade Stalin, I was as good as excommunicated. They played dirty tricks on me. They tore my books, threw dirt into my food, they literally spat on me a hundred times a day.

“I stopped talking altogether and went silent. It got to the point that I became like a mute. In order not to hear their abuse and curses, I used to stuff my ears with soft bread or cotton from my coat. They even persecuted me at night, all in the name of Socialism: a bright future, a better tomorrow, and all their other slogans. The tortured themselves became torturers. Don’t think that I have any illusions about the Trotskyists. I’ve realized one thing: the worst people are those who want to save the world. Among simple folk—merchants, skilled workers, the so-called little man—one can still find decent people. But among those who want to bring about the coming of the Red Messiah there is no truth, no compassion. What’s easier than torturing in the name of an ideal?

“It got to the point that the Polish prison guards began to stand up for me and demanded that I be left alone. I started asking them to put me among the criminal offenders, and when they at last obliged me the comrades exploited it and organized a protest demonstration opposing a political prisoner being put among criminals. In other words, they wanted me nearby to torture. This is how they behaved—those who ostensibly sat in jail for the sake of justice.

“Sitting among the thieves, pimps, and murderers was hardly a delight. They eyed me with suspicion. There prevailed an old hatred between the underworld and the politicals—ever since the times of 1905. But, compared with what I endured from the Stalinists, this was paradise. They stole my cigarettes and made off with portions of the packages that Sonia sent me, but they let me read my books in peace. Instead of ‘fascist,’ they called me ‘idiot’ and ‘good-for-nothing,’ which did less damage. It even happened sometimes that a thief or a pimp would pass me a piece of sausage or a cigarette from his own stash. What was there to do in the cell? Either you play cards—a marked and greasy pack—or you talk. From the stories I heard there, one could write ten books. And their Yiddish! The politicals babbled in the Yiddish of their pamphlets. It was not a language but some kind of jargon. The thieves spoke the real mother tongue. I heard them use words that astounded me. It’s a shame I didn’t write them down. And their thoughts about the world! They have a whole philosophy. At the time I went to prison, I still believed in revolution, in Karl Marx. I had all kinds of political illusions. Back outside I was completely cured.

“While I sat in jail, there developed in Poland a growing disappointment in Stalin. It swelled to the point that the Polish Communist Party was thrown out of the Comintern. Many of my persecutors had taken off for the ‘land of socialism’—where they were liquidated. I was told about one sucker who, having crossed the border, threw himself down and started kissing the ground of the Soviet Union, as Jews of yore used to do when arriving in the Land of Israel. Just as he lay down and kissed the red mud, two border guards approached and arrested him. They sent him to dig for gold in the north, where the strongest of men didn’t last more than a year. This was how the Communist Party treated those who had sacrificed themselves on its behalf.

“Then a new curse wriggled its way in: Nazism. It was Communism’s rightful heir. Hitler had learned everything from the Reds: the concentration camps, the liquidations, the mass murders. When I got out of jail, in 1934, and told Sonia what I thought about our little world and those who wanted to save it, she attacked me like the worst of them. The fact is that while I sat behind bars I’d become a kind of martyr or hero for the Trotskyists. I could have played the role of a great leader. But I told them: dear children, there is no cure for the human race. It was not the ‘system’ that was guilty but Homo sapiens itself, in the flesh. When they heard such heresy, they shivered with rage. Sonia informed me that she couldn’t live with a renegade. I’d had the luck of becoming a renegade twice over. It was a separate issue that, while I sat behind bars, she had lived with someone else. Hunchbacks are hot-blooded. There’s always a volunteer handy. He was a simple youth from the provinces, I think he was a barber. Little Rosa called him Daddy…”

III

“Don’t look so afraid! I won’t keep you here until tomorrow. You went away to America in 1935, if I’m not mistaken, and you know nothing about what happened later in Poland. What took place was an absolute breakdown. Stalinists became Trotskyists, while Trotskyists went into the Polish Socialist Party or the Bund. Others became Zionists. I myself tried to turn to religion. I went to a study house and sat myself down to learn the gemara, but for this one must have faith. Otherwise it’s just nostalgia.

“The anarchists raised their heads again—some of them still stood by Kropotkin, others became Stirnerists. We had guests in Poland. Ridz-Szmigli had invited the Nazis to hunt in the Białowieza Forest. Then came the Stalin-Hitler pact and the war. When they started to bomb Warsaw, those who were strong enough ran over the Praga Bridge and set out for Russia. Some had illusions, but I knew where I was going. Yet staying among the Nazis was not an option for me. I came to say goodbye to Sonia and found her in bed with the barber. Little Rosa started crying, ‘Papa, take me with you!’ These same cries follow me still. They torment me at night. They all perished. No one remained.

“I was in Bialystok when a number of Yiddish writers from Poland all at once became ardent Stalinists. Some lost no time and began denouncing their colleagues. People knew me as a Trotskyist and I was heading for certain death, but by then I’d arrived at a certain philosophy: We can’t live openly in this world. We have to smuggle ourselves through. People, like animals, must constantly hide themselves. If the enemy’s on the right, you go left. It goes left, you crawl right. This very philosophy—you can call it cowardice, it doesn’t bother me—has helped me. I knew where the informers were and I avoided them. A lot of leftists—half-leftists and converted leftists, so to speak—went to Vilna or Kovno, but I went on to Russia, not to the big cities but to little towns, villages, collective farms. There I found a different kind of Russian: generous, ready to help. There they laughed at communism.

“Until 1941, people got by somehow. When the war arrived, a famine broke out. Refugees on foot arrived by the millions. Others were brought in freight trains. Millions of Russians went to the front. I starved, slept in train stations, passed through all seven circles of Hell, but I avoided one thing: prison. I kept my mouth shut and played the role of a simple person, someone half-illiterate. I worked wherever possible. On collective farms and in factories I witnessed the thing called the communist economy. They simply destroyed the machinery. They ruined raw materials. It couldn’t even be called sabotage. It was a simple beastly indifference to anything that didn’t directly relate to them. The whole system was such that either you stole or you were dead. I entered a factory and the accountant, a fellow from Warsaw, conducted his accounting on books by Chekhov, Gogol, Tolstoy. He scribbled his numbers—obviously false—on the margins and above the printed type. You couldn’t get any blank paper there. People lived on stolen goods sold on the black market. You can’t grasp it unless you’ve seen it with your own eyes. If not for America—and had the Nazis not been such ferocious murderers—Hitler would have got as far as Vladivostok.

“I didn’t live—I smuggled myself through life. I became a worm that crawled from here to there. As long as it wasn’t trampled, it crept on. I was astonished to realize that the whole country was like this. We became like the lice that infested us. Until I arrived in Russia for the second time, I’d still had something in me that could be called romanticism or sexual morality. But with time I lost this, too. Millions of men lay scattered on the fronts and millions of wives lived with anyone who would take them. I slept with women whose names I didn’t even know. In the night I had females whose faces I hadn’t seen. I once lay with a woman on a bale of hay. She gave herself over to me and cried. I asked her, ‘Why are you crying?’ And she wailed, ‘If Grishenka only knew! Where is he, my little eagle? What have I made of him!’ Then she nestled up to me, crying. She professed, ‘To me you’re not a man but a candle for masturbation.’ She suddenly took to kissing me and wetting me with her tears. ‘What do I have against you? You’ve probably also left someone behind. A curse on fascism!…’

“In Tashkent, I got typhoid fever, which was later complicated by pneumonia. I lay in the hospital and around me people were constantly dying. Some Pole spoke to me and started telling me about all his plans. All at once he went silent. I answered him and he didn’t respond. The nurse came in and it turned out that he’d died. Just like that, in the middle of speaking. He suffered from scurvy or beriberi, and with these diseases people died, so to speak, without a preface. I became indifferent to death. I never believed this would be possible.

“You shouldn’t think that I came here just to get into your hair and tell you my life story. The fact is that I’m here and this means that I smuggled myself through everything—hunger, epidemics, murder, destruction, borders. Now I’m in your United States. I already have my papers. I’ve already been mugged in your America, and have already had a revolver held to my heart, too. A survivor with whom I crossed here on the ship has already worked his way up and owns hotels in New York. He took straight to business, forgot all the dead, all the killing. I recently found him in a cafeteria and he complained to me about his falling stocks. He married a woman who’d lost her husband and children, but she already has new children with him. I talk about smuggling myself and he’s a born smuggler. He’d already started smuggling in the German DP camps, where he waited for an American visa.… Yes, why did I come to you? I came with an idea. I beg you, don’t laugh at me.”

“What’s this idea?”

He waited a moment and lit another cigarette.

“You’ll think I’m crazy,” he said. “The idea is for all decent people to commit suicide.”

“Is that so!”

“You laugh, eh? It’s no laughing matter. I’m not the only one disappointed in the human race. There are millions of others like me. As soon as there is no longer any hope—what’s the point of hanging around to suffer fruitlessly and in vain? I read your writing back in Warsaw. I read you here. You are, as far as I know, the only writer who has absolutely no hope for mankind. You’ve lately taken to praising religion, but your religion is a religion of despair. You reduce everything to one point: this is God’s will. Perhaps God wants humankind to put an end to itself? I beg you, don’t interrupt me! There are scores of movements, who knows how many religions and sects—why shouldn’t there be a movement that preaches suicide? How long can you smuggle yourself only to be crushed in the end? My feeling is that millions of people are ready to end it all, but they lack the courage—the last push, so to speak. If millions of idiots are ready to die for Hitler and Stalin and all kinds of other scourges, why shouldn’t people want to perish as a protest? We should frankly throw back at God this gift of His: this despicable struggle for existence, which in any case ends in defeat. First of all, people must stop having children, bringing into the world new victims. Let the scumbags hope, let them fight for bread, sex, prestige, for the fatherland, for Communism, and for all kinds of other isms. If there remains among the human race a remnant of common sense, it should come to the conclusion that all this filth isn’t worthwhile.”

“My dear friend,” I said, “suicide can never be a mass movement.”

“How can you be so sure? What was the Battle of Verdun if not mass suicide?”

“People there hoped for victory.”

“What victory? They stationed a hundred thousand men and were left with sixty thousand graves.”

“Some survived. Some received medals.”

“Perhaps we should create a suicide medal?”

“You’ve remained a world-saver,” I said. “Suicide is committed alone, not with partners.”

“I read somewhere that in America there are suicide clubs.”

“For the rich, not for the poor.”

He laughed and exposed a toothless grin. He spat out his cigarette butt and stepped on it.

“So what should I do?” he asked. “Become rich? Perhaps I should. It would, actually, be like Job.”

****

Translator’s note:

Beginning in his early years in the United States, Isaac Bashevis Singer earned his living churning out texts for the Yiddish-language daily Forverts—an assortment of fiction, essays, journalism, advice, and memoir, often published in a hurry, under several pseudonyms. Later in his writing life, Singer worked on translating into English those stories he considered worthy of republication, editing and correcting them in the process.

When, in the course of my doctoral research, I came across the story “Job” (“Iyov”)—first published in Forverts in 1970, and later included by the late scholar Khone Shmeruk in a Yiddish collection titled “Der Shpigl” (“The Mirror”; Hebrew University, 1975)—I was convinced I’d find the story in English translation. Its themes of political disillusionment coupled with an inextinguishable search for salvation were tied to Singer’s larger body of work, and the story’s artistic accomplishment was confirmed by its inclusion in the Yiddish collection. The biblical title also indicated its potential significance. But I found nothing: not in any of Singer’s English-language collections, not among his uncollected or posthumously published stories, and not in the Isaac Bashevis Singer papers at the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. It seemed I’d have to read “Job” in the original.

I’d studied Yiddish, but my vocabulary was still relatively limited. To understand anything beyond the main premise, I had to look up words in the dictionary. As I began writing them down, I realized I was on my way to translating the story. I shared my translation of “Job” with a few colleagues in Jerusalem, and reviewed it with Eliezer Niborski, a young Yiddish teacher and native speaker. We were all struck by the story—especially its sharp yet compassionate final exchange—and surprised that it had yet to be published in English.

I decided to take another look at the list of the Singer papers in Texas. Knowing now what the story was about, I noticed a folder entry among Singer’s unidentified works that caught my eye. I ordered a facsimile of this typescript fragment and, as I suspected, found that Singer, together with Dorothea Straus, had indeed translated “Job”—but that the translation was not complete. The fragment of Singer’s translation attested to his distinct and idiosyncratic mastery of English, which I felt compelled to acknowledge in my rendition of the story. I ultimately decided to introduce the author’s hand by incorporating some of Singer’s own word choices—while also aiming to avoid mimicking or impersonating his singular English style.

Arrangements were made to publish my translation of the story. I showed it to Robert Lescher, the literary agent for Singer’s estate, who gave me some insight into Singer’s publication process. Mr. Lescher said that, after they’d begun working together, in 1970, Singer would bring his stories into the office. Mr. Lescher would comment on them, sometimes Singer would make changes, and only then would they be submitted to various editors for publication. At The New Yorker, Singer worked with the fiction editor Rachel MacKenzie to get a story into its final shape.

Mr. Lescher had minor reservations about a few lines in my translation where he felt the language didn’t flow. Based on his suggestions, I made a handful of adjustments that required my straying very slightly from the literal text. We were wary of editing a great writer who was no longer with us, but felt we could fine-tune the translation: ultimately, the responsibility falls to the translator to make decisions based on the original Yiddish text, whose publication Singer had approved.

A couple of days before the story was set to appear, I found myself again working with the folder list of the Singer papers at the Ransom Center. Looking for something else altogether, I came upon yet another entry among the unidentified works that caught my attention. I realized that it contained more, though still not all, of Singer’s translation of “Job.” The rest of the manuscript had apparently not been lost—it had merely been separated from the other parts and stuffed into a different slot.

The publication of “Job” had turned into a literary experience reminiscent of a chaotic Singerian universe—where coveted objects are misplaced, or purposely hidden by imps, only to reappear just before it’s too late. I used the additional pages to reconstruct some of my initial translation solutions—though again avoiding the temptation to replicate Singer’s signature linguistic choices in English. With the help of Arcadia Falcone of the Ransom Center, I am working to locate and reunite the missing pages of Singer’s translation of “Job.” And as in a Singer story, the story of this translation is yet to be continued…

— David Stromberg, Jerusalem, March-July, 2012

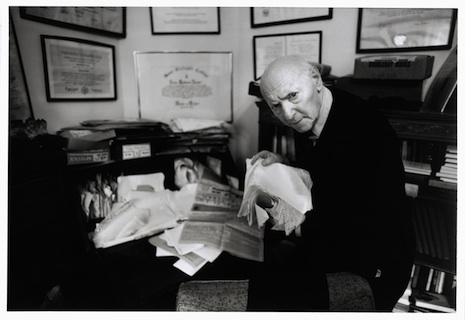

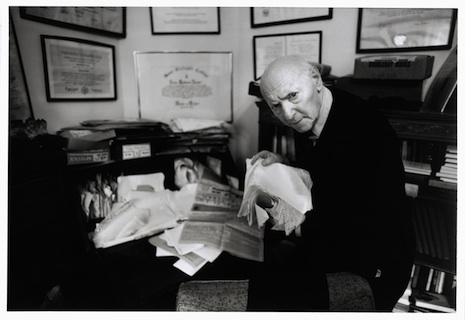

Photograph of Isaac Bashevis Singer by Bruce Davidson/Magnum.

Tags: "αστικό", Albanians, bourgeois, Christopher Hitchens, Communists, Fascists, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Jews, Job, Kafka, muslims, Nazism, Rebecca West, Russians, Solzhenitsyn, Stalinism, The New Yorker, the Red Messiah, Timothy Snyder, Turks, Vassily Grossman's Life and Fate, Walter Benjamin, Weil

ὁ σῖτος, ὁ οἶνος καὶ τὸ ἔλεον τοῦ δούλου σου — the wheat, wine and oil of Thy servant

ὁ σῖτος, ὁ οἶνος καὶ τὸ ἔλεον τοῦ δούλου σου — the wheat, wine and oil of Thy servant

Turks beating up young conscripts on the Bosporus Bridge, defending their democratic right to elect a dictator who has abolished Turkish democracy for the most part and soon will have the power to go after whatever’s left…Turkish “unity” in action.

Turks beating up young conscripts on the Bosporus Bridge, defending their democratic right to elect a dictator who has abolished Turkish democracy for the most part and soon will have the power to go after whatever’s left…Turkish “unity” in action.