********************************************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com

********************************************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com

*********************************************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com.

If you want to read more about the centuries-long friendship between my village of Dervićiane and neighboring Lazarat — famous pan-Balkanly for its marijuana cultivation and trade — read here: New Year in Derviçani: loving to come; dying to leave; fireworks; hate that won’t die… :

But soon, I think, the European Union got wind, no pun intended, of what most of the Balkans had already known for years and a huge police operation moved in, burst into every family’s compound and burned everything they had growing to ashes – “even their basil,” said one cousin of mine from Derviçani with glee. And her glee was made even greater because Lezarates’ humiliation was augmented by the fact that the police operation had entered the village through the upper mahalladhes of Derviçani (see map above), and — don’t quote me, what the fuck do I know — but I’m pretty sure with info from Derviçiotes who had been doing business – of some sort – with them for quite some time.

*********************************************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com.

@Purpura57912934 tweeted:

Forgotten Bonds: Albanian armed guards protected medieval Serbian churches & monasteries in Kosovo during the last centuries of Ottoman rule. The commanders were hereditary Vojvodas, the guards permanently lived on the church grounds & were most likely Laramans (Crypto-Orthodox).

Purpura begins his tweet with the words: “Forgotten Bonds”. I think it’s safe to assume that his intentions are to show how, in some indeterminate past, Albanian Muslims and Orthodox Serbs lived in harmony together in Kosovo and in such multicultural peace that it was Albanians who guarded the extensive and dazzling ecclesiastic art heritage of Kosovo Serbian Orthodoxy (instead of vandalizing it like they do now). But he concludes by saying that most of these guards were secretly Christian. And that of course belies the whole myth of “bonds” and tolerance and happiness and how “there is no compulsion in religion.”

Read about the Laramans on Wiki . It’s a fascinating page because it puts together a whole package of phenomena that all, to some extent, grew out of Ottoman defeat in the Great Austro-Turkish War at the end of the 17th century: the retaliatory violence against the still-Christian Albanian and Serbian population that lived in the western Balkans on the corridor where much of the fighting of the prolonged conflict had occurred; the flight of Serbs to the north; the Islamization of Albanian Catholic Ghegs who then settled in a depopulated Kosovo and the parts of southern Serbia that the Serbs had fled from*; the spread of Bektashism throughout the Albanian Balkans and how that form of Sufism may have grown out of the crypto-Christianity of much of the population and even from Janissaries (with whom the Bektashi order was widely associated) of Albanian extraction; and the spread of violent Islamization campaigns to the Orthodox, mixed Albanian-Greek population, of southern Albania later in the 18th and early 19th century.

A testament to this last phenomenon — the Islamization of southern Albania — is the obstinate Christianity of the region my father was from, the valley of Dropoli (shown above). There are several songs in the region’s folk repertoire that deal with the conversion pressures of the past, but one song that is heard at every festival or wedding and could be called the “national anthem” of the region, is “Deropolitissa” — “Woman of Dropoli.” Below are two versions; the first a capella in the weird, haunting polyphonic singing of the Albanian south (see here and here and here and especially here)**; and another with full musical accompaniment, so readers who are interested can get a sense of the region’s dance tradition as well (though in the second video the dress is not that of Dropoli for some reason). If you’re interested in Epirotiko music, listen for the “γύριζμα” or “the turn” — the improv’ elaborate clarinet playing — toward the end of the second video, 4:02; the clarinet is a Shiva-lingam, sacred fetish object of mad reverence in Epiros and southern Albania.

The lyrics are [“The singers are urging their fellow Christian, a girl from Dropull, not to imitate their example but keep her faith and pray for them in church.”]:

σύ (ντ)α πας στην εκκλησιά,

με λαμπάδες με κεριά,

και με μοσκοθυμιατά,

για προσκύνα για τ’ εμάς,

τι μας πλάκωσε η Τουρκιά,

κι όλη η Αρβανιτιά,

και μας σέρνουν στα Τζαμιά,

και μας σφάζουν σαν τ’ αρνιά,

σαν τ’ αρνιά την Πασχαλιά.

σαν κατσίκια τ’ Αγιωργιού.

…and go to church

with lamps and candles

and with sweet-smelling incense

pray for us too

because Turkey has seized us,

so has all of Arvanitia (Albania),

to take us to the mosques,

and slaughter us like lambs,

like lambs at Easter, like goats on Saint George’s day.

Until the first part of nineteenth century women in Dropoli used to wear a tattooed cross on their forehead, the way many Egyptian Copts, both men and women, still wear on their wrists; there are photographs of Dropolitiko women with the tattoo but I haven’t been able to find them. Here’s a beautiful photo, though — looks like some time pre-WWII — of Dropolitisses in regional dress.

Of course, as per my yaar, Ayesha Siddiqi, “I don’t think I can ever really be that close to people…” whose ancestors didn’t experience and stand up to religious persecution of the kind mine did.

************************************************************************

* Good to know something about the traumas of Serbian history before we rail against them and villainize them in a knee-jerk fashion. I think my best summary came from this post last year, Prečani-Serbs:

Prečani-Serbs: It’s doubtful that any Balkan peoples suffered more from the see-saw wars between the Ottomans and the Hapsburgs than the Serbs did. It’s easy to see why; Serbian lands are pretty much the highway for getting from the south Balkans to Vienna.

It’s the easiest proof there is that war always had “collateral damage” and civilian casualties. The Ottomans launched rapid campaigns up through to Vienna in 1529 and 1683. Both times they failed to take the city and retreated. Thank the gods, because the idea of Turkish armies at the walls of Vienna is even more terrifying than the idea of Arab armies in the Loire valley at Tours just 70 kilometers from Paris in 732. But in 1683 they not only failed to conquer Vienna, the Hapsburgs chased the retreating Ottomans across the Danube and as far south as Kosovo. That could have meant Serbian liberation from the Ottomans 200 years before it actually happened.

But then the Austrians made the fateful decision to retreat. I don’t know why. Perhaps they felt overextended or thought they were getting too deep into imperial overreach. And of course this meant horrific retaliatory violence on the part of Turks and local Muslims against the southern Serbs who had welcomed the Austrians as liberators. And an epic exodus of the Serbs northwards, in what are called the Great Migrations of the Serbs, began. This resulted in a massive shift to the north of the Serbian nation’s center of gravity and, perhaps most fatefully, marks the beginning of the de-Serbianization of Kosovo, which was the spiritual heartland of the Serbs. And an influx of increasingly aggressive highland Albanians, now Islamicized and emboldened in their impunity as such, only accelerated the departure of Kosovo Serbs to the north.

Conditions in northern but still Ottoman Serbia were better than in the south. But for many Serbs this was not enough. A great many crossed the Danube and settled in what is now the autonomous region of Vojvodina and the parts of Croatia called Slavonia and Krajina. Ironically, just as the Ottomans made Serbia prime recruiting country for their system of enslaving young boys to turn them into the most powerful unit in the Ottoman army, the Janissaries, the Austrians themselves also recognized that Serbs were, as always, good soldier material, and they invited Serbian fighters and their families into Austria’s border regions to protect the boundaries of the Hapsburg empire from possible Ottoman aggression.

So Prečani-Serbs, refers, very broadly, to those Serbs who went and settled in the borderlands of the Austrian empire; the term comes from “preko” or “over there” or “the other side”, across the Danube, Sava and Drina rivers, in other words, that were the borders between the Ottomans and Hapsburgs for centuries.

I don’t know whether Krajina Serbs from around Knin — shown in green in map below — are considered prečani or not, those from that part of Croatia that was largely Serbian until 1995, when it’s Serbian inhabitants were expelled with American help in what was the largest single act of ethnic cleansing in the Yugoslav wars, with some 200,000 Serbs expelled from their homes. Serbs are soldiers and poets, as I’ve quoted Rebecca West saying so many times; Croatians are lawyers; but with the detestable Milošević having abandoned Krajina Serbs (Venizelos-style), and with Americans arming, training them and watching their backs, Croats proved themselves to be formidable warriors indeed.

So, if one can put one’s biases aside, the poignant tragedy of this whole set of some 600-years of pain and trauma becomes clear. Bullied out of Kosovo over the centuries, Serbs move north, even so far north as to settle in Austria itself. Then, with no one’s help, they gather Serbs from Kosovo to the trans-Danube-Sava lands where they had settled over the centuries into one state. And less than 100 years later, they lose and are almost entirely expelled from both the Kosovo they had fled from and from the Krajina and Prečani lands they had fled to.

Good to know the whole stories sometimes.

** I’m pissed and disappointed at my χωριανοί, “landsmen”, who have totally abandoned this beautiful and UNESCO-protected form of singing. When I first went to Albania to see my father’s village for the first time in 1992, after the fall of its heinous Stalinist regime, and to meet relatives we only knew through the spotty correspondence that made it through the Albanian Communist καθίκια‘s censorship, a group of aunts and uncles of mine recorded two hours of traditional singing for me to take back to my father (my father put off visitting until much later, when he was very sick because I imagine he was afraid that it would be traumatic; of course, going back when he did in 2002, knowing it would be his one and last time was just as painful.)

(If you want to know more about my family’s history, see: Easter eggs: a grandmother and a grandfather.)

Now, thirty years later, no one except a few very old men still sing; they’ve totally left the playing field of the region’s song to neighboring Albanian villages; just like only a few young girls still wear traditional dress as brides, just like they’ve built horrible concrete polykatoikies without even a nominal nod to the traditional architectural idiom… Dance and dance music they’ve maintained, though they’ve sped up the tempo a little (compared to the second video above for instance) and that would have irritated my dad, since the aesthetic ideal of dance in the region is slow, almost motion-less, restraint — reminds you of Japanese Nōh drama. I carry the torch for him and get “grouchy”, as my friend E. says, when things get a little too uppity-happy on the dance floor.

************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com.

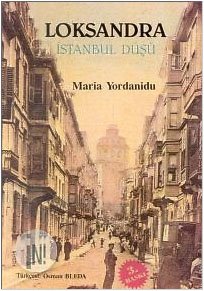

It’s actually hard to say which came first: whether Maria Iordanidou’s Loxandra was the first literary manifestation of the archetype of a Greek woman of Istanbul, or whether life imitated art and Politisses started unconsciously behaving like Loxandra. Joyful, funny, hovering and caring around all her loved ones but even strangers – even Turks – worldly for her degree of education and fundamentally cosmopolitan if even unawares, obsessed with good food, and always finding happiness and beauty and pleasure in the world, despite her people’s precarious position in their wider environment.

Iordanidou’s novel captures more perfectly than any other literary representation what Patricia Storace has called the “voluptuous domesticity” that Greeks associate with life in Anatolia and Constantinople. But what’s always moved me and struck me as so intelligent about the novel — each of the some ten or more times I’ve read it — is that it’s not all fun-and-games and yalancı dolma and Apokries in Tatavla and Politika nazia. Right along side the pleasure and humor rides a brutally honest portrayal of the “tolerant” and “diverse” Ottoman society that is a favorite fantasy of certain progressives, on both Greek and Turkish sides of the coin. Iordanidou doesn’t fall into that trap, just as she doesn’t fall into the alternate trap of portraying all Turks as murderous animals, along the lines of Dido Soteriou’s Matomena Homata (Bloodied Lands) or Veneze’s Aeolike Ge (Aeolian Earth). She simply goes for the starkest realism: Ottoman Turks/Muslims and their subject peoples didn’t live together in harmony but rather lived in parallel universes that rarely intersected; the novel takes place at a time when – as Petros Markares points out in his essay in the book’s latest edition – “life was heaven for the minorities and hell for Muslims.” But even in that paradise, when the two parallel universes collided, the result was hellish for everyone.

I’ve translated the chapter that takes place during the Hamidian massacres of Armenians in 1896, particularly the shockingly urban episode that occurred in Istanbul. In August of that year, the Dashnaks, Armenian freedom-fighters-cum-terrorists took hostages at the Ottoman Bank in Karaköy and the operation turned into a mini-civil-battle with groups of Armenians and Turks taking up position on either side of the Galata Bridge.

Retribution against the ordinary Armenian populace in Constantinople was swift and brutal. Ottomans loyal to the government began to massacre the Armenians in Constantinople itself. Two days into the takeover, the Ottoman softas and bashibazouks, armed by the Sultan, went on a rampage and slaughtered thousands of Armenians living in the city.[11] According to the foreign diplomats in Constantinople, Ottoman central authorities instructed the mob “to start killing Armenians, irrespective of age and gender, for the duration of 48 hours.”[12] The killings only stopped when the mob was ordered to desist from such activity by Sultan Hamid.[12] They murdered around 6,000[1] – 7,000 Armenians. Within 48 hours of the bank seizure, estimates had the dead numbering between 3,000 and 4,000, as authorities made no effort to contain the killings of Armenians and the looting of their homes and businesses.

Loxandra and her family live through the massacring of their Armenian neighbors in Pera in terror, hiding inside their shuttered house for a week, till they finally run out of water and have to start interacting with the neighborhood vendors. Iordanidou does take a swipe at Turkish passivity and fatalism though in the closing part of the chapter as Loxandra hears repeatedly from the Turkish merchants she has to deal with, in reference to the killing: “Yağnış oldu.” “That was a mistake.” This “Yağnış oldu” chimes like a bell or rather a kick in the gut on the chapter’s last page: “Thousands dead, families annihilated, their homes looted, their churches destroyed… Yağnış oldu”

Shit happens, in other words.

Loxandra soon starts to forget, or at least pretends to. In the end, the chapter is a disturbing look at the compromises we make in order to go on living with the Other, despite the evil he may have done you, or you him. Otherwise life would be intolerable. For “…too much sorrow doth to madness turn…” Loxandra concludes in the final sentence.

Loxandra: Chapter 5

Glory be to God, because “To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven…A time to be born, and a time to die…a time to break down, and a time to build up…”

Loxandra just figured that for her to suddenly find herself living in the Crossroad*(1) that meant that the time had come and that this had to be her world from now on. She accepted her new life the way that she accepted Demetro’s death. What can you do? That’s how that is.

The Crossroad was nothing like Makrochori [Bakırköy], and the beautiful old life she had there – it was like a scissor had come and snipped it off — slowly became a sweet receding dream. Cleio started to yearn for twilight in Makrochori, the sky, the sea, their garden and the shade of their plane tree. She had even lost her father’s library, because during the move to Pera, Thodoro had pilfered most of it and now all she was left with were Kassiane, Pikouilo Ali Ağa and Witnesses at a Wedding. She started to avoid the cosmopolitan life of Pera, which she at first had thought heavenly, and she lamented her lost paradise. Exactly opposite to her mother.

Because Loxandra never wept for lost heavens. Nor did she ever go in search of joy. It was joy that went in search of Loxandra. And it would usually pop up in the most unexpected moments. The angel would suddenly descend and stir the waters in the fount of the Virgin of Baloukli and for Loxandra it was like she had been baptized anew.

Glory be to God. And great be the grace of the Virgin.

The fat little ducklings of August and the okra make good eating. It’s a sin to let August pass without eating ducklings with the okra.

So on the eve of the Virgin’s Loxandra bought ducklings to cook them with the okra, and despite her exhaustion, she went down into the kitchen to start preparing the birds. She was especially tired because the day before she had stocked up fuel for the winter. She filled the cellar with charcoal, and then she’d call the Kurds to come hack up the lumber she would use for the stoves.

In the City at that time, just as your milkman was Bulgarian, your fishmonger Armenian, your baker from Epiros, so your lumber supplier was a Kurd. So Loxandra called the “Kiurtides” to come chop up her winter stock of lumber. Early in early morn’ — όρθρου βαθέος — they would dump a good thirty “chekia” of tree trunks and thick boughs and then the Kurds would come, brawny giants from deep in Anatolia in salwar and black kerchiefs wound around their fezzes and with their shiny, well-sharpened cleavers to chop up the wood. The Kurds were meraklides [connoisseures] when it came to their blades. Even all the way in his village in the depths of Kurdistan, the Kurd could never be separated from his cleaver, and when the time came for him to emigrate his mother would present his cleaver to her son, the way a Spartan woman gave her son his shield. And when a young Kurd got to an age of fourteen or fifteen and started feeling the first longings of his youth, he never took flowers in hand. Instead he’d take his knife and go about the mahalades crying out: “Dertim var, dertim”… “I’m in pain, in longing” and would look around to see if any of the shutters or windows all about would open. The young girl that would first answer his call would open her window and cry: “Dertine kurban olurum”, meaning “I’ll sacrifice myself to your longings”. And the young man would exclaim: “Bende baltaim burada vururum”, meaning “And so I nail my knife here.” Then he went home and sent his mother to retrieve his knife and at the same time, get to know her future daughter-in-law.

That’s how important the cleaver was for a Kurd. And you’d be better off cursing out his Prophet rather than saying anything offensive about his cleaver.

Loxandra was afraid of Kurds, just the way she was afraid of Turks. But when it came to important things like her yearly supply of firewood, well…there was no holding her back nor kid gloves to wear in treating them:

“Does this fit, you son-of-a-dog?” she’d yell, suddenly fearless and waving a big, bulky knot of wood above the Kurd’s head. “Does this fit, bre, in my stove?”

She would get so angry that she even might have said something about his cleaver.

But oddly enough the Kurds never got angry and never felt insulted by her, and would do any favor she wanted. They would stack the chopped up lumber in her cellar and their departure was always warm and accompanied by the usual güle güle and reciprocal good wishes and a light winter, may-it-be, and here…take this for your little boy and here take this for your wife, and all the rest.

That night, Loxandra was exhausted and all night long she saw bizarre dreams of sharp meat cleavers and a big butcher’s block piled with chopped meat. She just attributed the dreams to her experiences that day with the Kurds. “Oh”, she thought upon waking: “Ιησούς Χριστός Νικά” “Jesus Christ Victor”…and she went down into the kitchen to brown the ducklings.

How could she know what the future had in store for them? How could she know that the treaty that was signed eighteen years before in San Stefano had been revised and revised again so that Bulgaria could be an autonomous state, Romania and Montenegro were now independent, Russia took Kars and Ardahan and Batumi, Britain took Cyprus, Greece got Thessaly and a part of Epiros, but the Armenians got nothing out of all that had been promised to them, and they started an uprising, so that Sultan Hamid roused up his people, and he brought Kurds with their cleavers and they had organized a massacre of Armenians…right there…in the middle of the streets of the City…on the eve of a feast day like this…the Assumption of the Virgin… How could she possibly know all of that?

So, blissful and clueless, she went down to prepare the ducklings, and she was in a happy mood, but in just such a good mood that morning. The day before they had received a letter from Giorgaki asking for Cleio’s hand in marriage. The letter was a bit nutty, but what was important is that he wanted to marry Cleio. It started like this:

“In these difficult moments my mind races to you and only you, my refuge and haven, my peaceful port…”

And riding on that inspiration – and drunk – Giorgaki wrote that he missed his boat and that he had gotten stuck in Genoa with Epaminonda, alone and abandoned and penniless, because, being human, they had had a bit to drink to forget their dertia and night had fallen on them in the alleyways of Genoa, and in the dark Epaminonda had started bugging a Catholic priest: …psss…psss…thinking he was a woman, and the neighbors had gotten all riled up and Epaminonda had gotten arrested, but the Greek consul in the city was a countryman of Giorgaki’s and he got the authorities to release Epaminonda from the holding pen, and in a few days the consul would put them on a ship to Constantinople to celebrate the engagement — that is, if Loxandra accepted him as a son-in-law. And before closing, he added: “My lips will never again touch even a single drop of alcohol.”

How could she not be happy?! She set the pan on the fire and as soon as the birds started to soften up, she tasted the sauce to check the salt. Suddenly she heard the stomp of running feet in the street.

“Bre, Tarnana, get up and go out and see what’s going on”, she said to him.

But Tarnana was too tired to go see because to see he had to climb up onto the sink because the kitchen was in the basement. So all he could see the was the sight of running feet. But Loxandra grabbed a chair for herself and climbed on top of it to get a better view. And what does she see? A Kurd with his cleaver in hand was trying to break down the door of Monsieur Artin.(**2)

HA! The bloody dog, may-a-wretched-year-befall-him!

She got down off the chair and grabbed the large soup ladle.

“Just wait and see what I’ll do to him!”

She gathered up her skirts and ran up the stairs. But she came crashing into Cleio.

“It’s a massacre, mother, a massacre!” cried Cleio in a semi-faint.

Loxandra paid her no mind.

“What massacre shmassacre you talking about, bre? Some Kurd is looking to break down Monsieur Artin’s door. Get outta my way!”

Sultana came down too and along with Cleio and Tarnana they stuffed up her mouth so that her cries couldn’t be heard on the street. They closed the shutters and they all hid in the charcoal cellar.

But even in the cellar you could hear the blows from the street, the running feet, and the dying cries of the wounded. There would be a short few moments of quiet and then it would start again. Any time there was a bit of silence, Loxandra would grab her ladle.

“It’s just the Kurds for heaven’s sake, may-the-Devil-take-them-and-carry-them-off! Let me go see what’s happening!”

When the frenzy finally stopped an employee from Thodoros’ office came to bring them some groceries and to see how they were. He said there had been a mass slaughter of Armenians but that no Greeks had been hurt unless they were harboring Armenians in their house, and Thodoro sent the message that God forbid anyone find out you’ve got Tarnana in the house. In the Crossroad things had calmed down, but the killing was continuing in the suburbs.

That was enough to finally scare Loxandra and she hid Tarnana under her bed. She was afraid to get near the window or even open the shutters. The street vendors started to come by as usual. The salepçi (***3) came by. The offal-vendor came by, and as soon as they smelled him the cats started growling. She locked them up in the charcoal cellar. “Shut up, bre, they’ll come and cut your throats too.” The milkman came and knocked. No one inside made a sound. We’ll do without milk. Drink tea. But on the seventh day the water supplier came by and she had to open up because they were running out. Hüseyn came in limping and emptied two goatskins into the clay amphora they stored water in.

Hüseyn says good bye sweetly and soon the egg-seller comes knocking on her window.

“Kokona (****4), Aren’t you going to buy any eggs?”

Loxandra cracked open the window, took a look at him, and thought: “Could my egg-vendor Mustafa be a Hagarene Dog (*****5) too?”

The next morning the street watchman came by to say hello, expecting his usual cup of coffee.

“Haydi, Tarnana, make him some coffee.”

She opened up the front door and sat on the steps, thinking again: “Is he or isn’t he?” Finally she couldn’t contain herself:

“Bre, Mehmet, I want you to tell me the truth, but, I mean, I want the truth, ok? Were you out on the street the other day with the killings? But tell me the truth.”

“Valah! Billah! Mehmet wasn’t involved.”

“Oooff… And I was going to say…” And she began to sob. “Why such madness? What did poor Monsieur Artin do to them and they slaughtered him like that? No, Tell me! What did he do?”

“Vah, vah, vah”, Mehmet said.

“Vah, vah, vah”, said the liver vendor a bit later.

“Vah, vah, vah”, said the chickpea vendor too. “Yağnış oldu.” “That was a mistake.”

Some ten, some twenty thousand people were murdered. Their homes were looted. Their churches destroyed. Whole families were wiped out…“yağnış oldu.”

The dogs licked the blood off the sidewalks and life started again as if nothing had happened.

Tarnana came out from under the bed too, Elegaki came over too and they all got together in the kitchen to prepare the sweets for Cleio’s engagement. Loxandra wiped her tears and made sweet out of sorrow, because that’s how that is. And let me tell you something, too much sorrow, well…too much sorrow doth to madness turn. I mean, there are limits!

************************************************************************

*(1) The Crossroad, Το Σταυροδρόμι, (above) is what Greeks called the spot in central Pera where the now Istiklâl Caddesi (the Isio Dromo or the Grande Rue) intersects with the steep uphill Yeni Çarşı Caddesi (never understood what the New Market, which is what Yeni Çarşı means, refers to) coming up from Karaköy, and the Meşrutiyet Caddesi which then takes a curve at the British consulate and ends up — now — in one of the most dismal urban plazas in Istanbul and a run-down convention center, that were built over a pleasant little park that was built in turn over an old Catholic cemetery. Mercifully, one side of the street is still architecturally intact and you still get one of the most splendid views of the Horn and the western part of the Old City from there. By the Gates of Galatasaray Lycée, that’s still the starting place for demonstrations and protests — whatever are allowed, anyway… By the Cité de Pera arcade and the central fish market (never understood why the fish market is up at the top of one of Istanbul’s hills and not on the seafront somewhere) that is full of both trashy, touristy restaurants and really good meyhane finds as well, once almost all owned by Greeks and Armenians.

If Pera is the center of Istanbul, the Crossroad is the center of Pera. And in Greek usage it meant the whole surrounding neighborhood as well.

(**2) Artin immediately registers to a Greek-speaker as an Armenian name.

(***3) Salep (Salepçi is a salep vendor) is a hot drink made from ground dried orchid tubers, milk I think, and cinnamon on top. It’s supposedly fortifying — in what way common decency prevents me from saying — but aside from the fact that “orchid” comes from the Indo-European root for “testicle” (as in “αρχίδια,” or as in “στα αρχίδια μου”) the finished drink has a slightly creepy, slippery texture and translucent color that definitely reminds one of semen. I happen to really like it, but I don’t know if that’s just because of its status as a historical remnant or oddity. You can find it in Athens too, like on Ermou, still. But it’s a hot drink, meant for wintery consumption, so it’s weird for Iordanidou to have a salepçi coming around on the street in the middle of August.

(4****) “Kokona” is a term used in historical literature to address not just Christian women, but Greek women, Ρωμιές “Roman” women, specifically. It’s never used to address Armenian or Jewish women, for example. It appears in literature and various accounts dating from even early Ottoman times. In the Byzantine Museum here in Athens (the name of which, at some point recently, was changed to the Byzantine and Christian Museum — in case we forget that Byzantium was a Christian culture 🙄) there are several pieces of ecclesiastic embroidery: priests’ stoles, Epitaphio shrouds — that date from the 16th and 17th century, and are attributed to specific women: Kokona Angela, Kokona Marigo, so it was more than just a slang term of address. No one I know can tell me the root of the word, nor can anyone say why it was used just for Greek women and not other gâvur/kaffr women.

(5*****) “Hagarene Dogs” – Αγαρηνά Σκυλιά – is an obviously unpleasant term used as far back as mid-Byzantine times to refer to Arabs/Muslims. The rub is that it was the first peninsular Arabs and Muslims who themselves identified with the term. Hagar, as we know, was the slave wife of Abraham, who bore him a child, Ishmael, because his own wife, Sarah, was already 80 years old plus and unable to have a child. Then the angels came to visit and told Abraham that Sarah would bear him a child; Sarah heard from the kitchen and laughed with good Jewish irony. But indeed, she did bear him a son, Isaac. And Abraham promptly tossed Hagar and Ishmael out into the desert, but they were saved by an angel that descended and struck the ground out of which a fresh spring of water gushed:

Hājar or Haajar (Arabic: هاجر), is the Arabic name used to identify the wife of Ibrāhīm (Abraham) and the mother of Ismā’īl (Ishmael). Although not mentioned by name in the Qur’an, she is referenced and alluded to via the story of her husband. She is a revered woman in the Islamic faith.

According to Muslim belief, she was the Egyptian handmaiden of Ibrāhīm’s first wife Sara (Sarah). She eventually settled in the Desert of Paran with her son Ismā’īl. Hājar is honoured as an especially important matriarch of monotheism, as it was through Ismā’īl that Muhammad would come. [my emphasis]

Neither Sara nor Hājar are mentioned by name in the Qur’an, but the story is traditionally understood to be referred to in a line from Ibrāhīm’s prayer in Sura Ibrahim (14:37): “I have settled some of my family in a barren valley near your Sacred House.”[20] While Hājar is not named, the reader lives Hājar’s predicament indirectly through the eyes of Ibrāhīm.[21] She is also frequently mentioned in the books of hadiths.

I have no idea why early Arabs chose — not that it was a conscious process, but being unconscious makes its function even more powerful — out of all of Jewish scripture, to consider themselves and Muhammad descended from a scorned slave woman and her unwanted son, the first-born of Abraham cast into the desert, especially given how Ishmael is described in Genesis:

Genesis 16:12 “He shall be a wild man; His hand shall be against every man, And every man’s hand against him.”

Unless “a wild man” suited their needs. Almost to an archetypal degree, conquest narratives justify themselves as retribution for a historical wrong, or as a necessary process by which the morally and ethically superior impose themselves on the inferior: from the Israelites and Canaan, to the Romans taking revenge for their defeated Trojan ancestors, to the Turkic Conquest of Rum and the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, to the Spanish Conquest of the Americas, to American Manifest Destiny, to Nazi lebensraum to the current Islamist and Turanian rantings of Mister Erdoğan and the bitchy historical insults he’s constantly hurling our way.

And wouldn’t you know, just today, Mr. Erdoğan gives us a Friday sermon that pretty much says it all and in language far less wordy than mine:

“Turkish Conquest Is Not Occupation or Looting – It Is Spreading the Justice of Allah”

Loxandra, of course, doesn’t know any of this. She’s just heard the legends of the “Hagarene Dogs” growling at the walls of the City before the conquest, and imagines them to be real barking dogs who can take human shape and turn into her milkman or egg vendor.

And now I need some good salsa, ’cause the legacy of “our parts” — τα μέρη μας — can weigh on you like a glob of hardened lead.

************************************************************************

Write us: with comments or observations, or to be put on our mailing list or to be taken off our mailing list, contact us at nikobakos@gmail.com.

I’ve been silent for a year, more or less. And the reason is pretty simple: Turkey. It’s been hard to watch a country you feel (or should) so close to, are for better or worse geographically adjacent to, (mostly worse), and which is so key in every way to the subject matter and internal structure of this blog, implode in such spectacular fashion and not have something to say.

And yet I didn’t have anything to say that could do justice or offer any insights into what was happening. I look back at a blog entry from the end of 2015 about my arriving in C-Town on November 2nd, the day after Turks gave Erdoğan a parliamentary reward for inciting the unspeakable violence that had already occurred — and would soon start spiralling exponentially out of control — instead of punishing him for it, and note that I feel an internal tectonic shift towards the place and its people; a weird, kind of science-fiction-like creepiness and discomfort…City of Zombies.

But every time I’d try to say something, events would overgallop and trample me and I’d say nothing again. Instead of posting here, I started writing acerbic, aggressive-aggressive emails to small groups of friends – partly to get my bile out, partly to hurt some of them. I felt myself starting to fall back on ancestral nastiness: Greek clichés of Turks as inherently slow-geared: a kind of dumb manipulable mob, one who’ll sooner or later be steered by the powers-that-be that they revere so idiotically into finding a way to take out their society’s dysfunction on us.

It’s been nice to be in Jiannena since Christmas. (“Jianniotes’ Jianniotiko passion for their Jiannena is well-known…” states with unapologetic Jianniotiko pride the introduction to a really interesting book I’,ve stumbled across here about the little known late Roman and early Byzantine history of the city.*) It is an addictively pleasant town and on December 30th some friends of mine from Istanbul came to spend a few days with me here. We were glad to see each other. It had been a long time. The weather was chilly but bright and sunny. The raki bracing. And to show two Turkish friends around a city whose primary tourist sites are Ottoman, and its general ‘Ottomaness,’ is the kind of irony in such matters that I love.

So I think it might have been a kind of perverse blessing to be with them New Year’s morning after the Reina attack in Ortaköy. Here were two real people I love, in pain: not straw men to beat up or take out my frustrations on. And that made a difference. It slows down your thinking. It doesn’t let you cut emotional or intellectual corners. I might actually have something to say soon.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

*************************************************************************

*

(click)

This is a piece of graffiti that appeared in the Slovenian capital city of Ljubljana in 1992, at the beginning of the worst period in the Yugoslav wars and after Slovenia had become independent. “Burek [‘börek’ in Turkish, pronounced exactly like an umlauted German ‘ö’]? Nein Danke.” Burek? Nein Danke. “Burek? No Thank You.” What a silly slogan, ja? How innocuous. What could it possibly mean? Who cares? And how can NikoBako maintain the bizarre proposition that a piece of graffiti in a rather pretentious black-and-white photograph is an important piece, in its ugly, dangerous racism, of the break-up of Yugoslavia.

Back up then. There are certain — usually material — aspects or elements of Ottoman life in the Balkans, which, even for Christians in the region, despite the centuries of unfortunate hate and reciprocal bloodletting (and no, I don’t think pretending that wasn’t true or that “it wasn’t that bad” is the key to improving relations between us all now; I think the truth is the key), remain objects of a strange nostalgia and affection. They linger on — even if unconsciously, or even as they’re simultaneously an object of self-deprecating humour or considered homely backwardness – as evidence that Ottoman life had a certain refinement and elegance that these societies have now lost. You sense this often intangible and not explicitly acknowledged feeling in many ways. Folks from my father’s village, Derviçani, for example, now go to Prizren in Kosovo to order certain articles of the village’s bridal costume because they can no longer find the craftsmen to make them in Jiannena or Argyrocastro, and they’re conscious of going to a traditional center of Ottoman luxury goods manufacture. You feel it in what’s now the self-conscious or almost apologetic serving of traditional candied fruits or lokum to guests. Or still calling it Turkish coffee. Or in Jiannena when I was a kid, when people still had low divans along the walls of the kitchen where they were much more comfortable than in their “a la franca” sitting rooms. 1* Perhaps the sharpest comparison is the way the word “Mughlai” in India still carries implications of the most sophisticated achievements of classical North Indian…Muslim…culture, even to the most rabid BJP nationalist. 2**

There are some places where this tendency is stronger than in others. Sarajevo and Bosnia are obvious; they still have large Muslim populations though and, after the 90s, Muslim majorities. But Jiannena – which I’ll call Yanya in Turkish for the purposes of this post, the capital city of Epiros and one often compared to Sarajevo: “a tiny Alpine Istanbul” – is also one such place. Readers will have heard me call it the Greek city most “in touch with its Ottoman side…” on several occasions. You can see why when you visit or if you know a bit of the other’s past: or maybe have some of that empathy for the other that’s more important than knowledge.

About half Greek-speaking Turks before the Population Exchange, Yanya was a city the Ottomans loved dearly and whose loss grieved them more than that of most places in the Balkans. It’s misty and melancholy and romantic. It has giant plane trees and had running waters and abundant springs in all its neighbourhoods, along with a blue-green lake surrounded by mountains snow-capped for a good five or so months of the year. It experienced a period of great prosperity in the eighteenth and especially nineteenth century, when it was not only a rich Ottoman commercial city but also a center of Greek education: “Yanya, first in arms, gold and letters…” – and, especially under the despotic yet in certain ways weirdly progressive Ali Paşa, was the site of a court independent enough to conduct foreign policy practically free of the Porte and fabulous enough to attract the likes of Pouqueville and Byron, the latter who never tired of commenting on the beauty of the boys and girls Ali had gathered among his courtiers, as Ali himself commented profusely on Byron’s own. All the tradition of luxury goods associated with the time and the city: jewelry, silver and brassware, brocade and gold-thread-embroidered velvet, sweets and pastries – and börek – still survive, but are mostly crap today, even the börek for which the city used to be particularly famous, and your best luck with the other stuff is in the city’s numberless antique shops.

It also, unusually, and which I like to ascribe to Yanyalıs’ good taste and gentlenesss, has preserved four of its mosques, the two most beautiful in good condition even, and on the most prominent point of the city’s skyline. It would be nice if they were opened to prayer for what must be a sizable contingent of Muslim Albanian immigrants now living there — who are practically invisible because they usually hide behind assumed Christian names — but that’s not going to happen in a hundred years, not even in Yanya. Maybe after that…we’ll have all grown up a little.

And, alone perhaps among Greek cities, only in Yanya can one open a super-luxury hotel that looks like this, with an interior décor that I’d describe as Dolmabahçe-Lite, call it the Gran Serail, and get away with it. 3***

Digression Bakos. What’s the point? What does this have to do with Yugoslavia? I’m not digressing. I’m giving a prelude. “People don’t have the patience for this kind of length on internet posts.” I don’t post. I write, however scatterbrainedly. And not for scanners of posts. For readers. However few have the patience.

So. Croatians don’t eat börek. The prelude should have been enough for me not to have to write anything else and for the reader to be able to intuit the rest. But for those who can’t…

The graffiti on the wall in the photo at top is dated 1992, but I think it had appeared as a slogan as early as the late 80s when Slovenes and Croats started airing their completely imaginary grievances against Serbian domination of Yugoslavia and making secessionary noises. What it meant is that we, Hapsburg South Slavs, were never part of the Ottoman Empire and therefore never were subject to the barbaric and development-stunting influences of said Empire that Serbs and whoever those others that live south of them were, and therefore have the right to be free of the intolerable yoke of Serbdom. We don’t eat burek. Not only do we not eat burek, but you offer it to us and we’ll refuse in German – “Nein Danke” – just to prove how much a part of the civilized Teutonic world of Mitteleuropa we are. 4*** (I think it was Kundera who wrote about the geographical ballooning of “Central Europe” after the fall of communism, till “Eastern Europe” finally came to mean only Russia itself. ‘Cause as we now see, even Ukraine is part of Central Europe.)

Why this yummy pastry dish was singled out as a sign of Ottoman backwardness and not, say, ćevapi or sarma, I can’t say.

Ćevapi — köfte, essentially — (above) and sarma (stuffed cabbage) below.

And when I talk about Hapsburg South Slavs I’m obviously talking about Croats, because, let’s face it, who cares about Slovenes? And there may be very few, if any, compelling historical or cultural reasons of interest to care about Croatians either, except, that as most readers must know by now, I consider them the people most singularly responsible for the Yugoslav tragedy. And this post is my chance to come clear about why I feel that way. There may be lots of interpretations of what the “Illyrianist” intellectuals of Vienna and Novi Sad and Zagreb had in mind when they started spouting theories of South Slav unity in the nineteenth century; countless theories about how Yugoslavia or the original Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed; many analyses of what happened in Paris in 1919 and what kind of negotiations led to the Corfu Declaration; and reams of revisionist stuff written about exactly what Croatia wanted out of this union. But, for me, one basic fact is clear: that Croatians were always part of Yugoslavia in bad faith; that they wanted something out of the Serb efforts and Serbian blood that was decisive in defeating Austria in WWI, but that that something was independence, or greater autonomy within an Austria that they probably never expected to be dismembered the way it was – anything but what they felt was being subjected to Belgrade. And that became immediately clear upon the formation of the state when they – being, as Dame Rebecca calls them, good “lawyers” – began sabotaging the normal functioning of the Yugoslav government in any way they could, no matter how more democratic the Serbs tried to make an admittedly not perfect democracy, no matter how many concessions of autonomy Belgrade made to them. If there were any doubt as to the above, even when Radić and his Croatian People’s Peasant Party had turned the Skupština into a dysfunctional mirror image of today’s American Congress, even when a Macedonian IMRO activist working in tandem with Croatian fascists assassinated Serb King Aleksandr in Marseille in 1934, it was subsequently made brutally clear by the vicious death-spree Croatian, Nazi-collaborating fascism unleashed on Serbs during WWII, a true attempt at ethnic cleansing that dwarfs anything the Serbs may have done during the 90s — which is dwarfed again by what Croatians themselves did in the 90s again: the most heinous Nazi regime, “more royalist than the king,” as the French say — more Nazi than the Nazis — to appear in Eastern Europe during WWII. And they have not been even remotely, adequately, held to account by the world for any for any of the above; all this ignored, even as the West maintains a long list of mea-culpas it expects Serbs to keep reciting forever.

King Aleksandr of Yugoslavia (click)

And so, when they got their chance in the 90s, with the backing of a newly united, muscle-flexing Germany, Croatians abruptly and unilaterally and illegally declared their long-wished for (but never fought-for) independence. And so did Slovenia; but again, who cares about Slovenia? It was a prosperous northern republic that may have held the same Northern-League- or-Catalan-type resentments against a parasitic south that was draining its wealth, but it was ethnically homogeneous and its departure left no resentful, or rightfully fearful, minorities behind. But Croatia knew, when it declared its independence – as did, I’m sure, their German buddies – that they were pulling a string out of a much more complex tapestry. And did it anyway. And we all saw the results. 5*****

So when a Croat says “Nein Danke” to an offer of burek, without even the slightest concern about his past reputation and avoiding any German associations, it is for me a chillingly racist and concise summation of Saidian Orientalism, a slogan that sums up not only the whole ugliness of the tragic, and tragically unnecessary, break-up of Yugoslavia, but the mind-set of all peoples afflicted with a sense of their being inadequately Western, and the venom that sense of inadequacy spreads to everything and everyone it comes in contact with. I’ve written in a previous post about Catalan nationalism:

All of us on the periphery, and yes you can include Spain, struggle to define ourselves and maintain an identity against the enormous centripetal power of the center. So when one of us — Catalans, Croatians, Neo-Greeks — latches onto something — usually some totally imaginary construct — that they think puts them a notch above their neighbors on the periphery and will get them a privileged relationship to the center, I find it pandering and irritating and in many cases, “racist pure and simple.” It’s a kind of Uncle-Tom-ism that damages the rest of us: damages our chances to define ourselves independent of the center, and damages a healthy, balanced understanding of ourselves, culturally and historically and ideologically and spiritually. I find it sickening.

(see also: “Catalonia: ‘Nationalism effaces the individual…'” )

We’re signifying animals. And our tiniest decisions — perhaps our tiniest most of all – the symbolic value we attribute to the smallest detail of our lives, often bear the greatest meaning: of love; of the sacred; of a sense of the transcendent in the physical; of our self-worth as humans and what worth and value we ascribe to others; of hate and loathing and vicious revulsion. Nothing is an innocently ironic piece of graffiti – irony especially is never innocent, precisely because it pretends to be so.

And so I find anti-börekism offensive. Because a piece of my Theia Vantho or my Theia Arete’s börek is like a Proustian madeleine for me. Because I’m not embarrassed by it because it may be of Turkish origin. Because I think such embarrassment is dangerous – often murderously so, even. And because I think of eating börek — as I do of eating rice baked with my side of lamb and good yoghurt as opposed to the abysmally soggy, over-lemoned potatoes Old Greeks eat – as an act of culinary patriotism. 6****** And a recognition that my Ottoman habits, culinary and otherwise, are as much a part of my cultural make-up as my Byzantine or even Classical heritage are. Because just like Yugoslavia, you can’t snip out one segment of the woop and warf and expect the whole weave to hold together.

******************************************************************************************************************************************************************

*1 One thing judo taught me — or rather what I learned from how long it took me, when I started, to learn to sit on my knees and flat feet — is how orthopedically horrible for our bodies upright, Western chairs and tables and couches are. (By couch here I don’t mean the sink-in American TV couch, which you sink into until you’re too fat to get out of — that’s another kind of damage.) Knee and lower back problems at earlier ages are far more prevalent in the Western world precisely because of these contraptions that artificially support and distort our body weight in destructive ways. I remember older aunts in Epiros, in both Jiannena and the village, being able to sit on a low divan on the floor and pull their legs up under their hips with complete ease — women in their eighties and nineties and often portly at that — because their bodies had learned to sit on the floor or low cushions all their long and very mobile lives; they looked like they didn’t know what to do with themselves when you put them in a chair. I’m reminded of them when I see Indian women their age at mandirs, sitting cross-legged, or with legs tucked under as described, through hours-long rituals, rising to prostrate themselves and then going down again, and then finally just getting up at the end with no pain and no numbness and no oyyy-ings.

**2 The two masterpieces of this point: the celebration of the sophistication and sensuality of the Ottoman sensibility and a trashing of Neo-Greek aesthetics — and by extension, philisitinism, racism and Western delusions — are Elias Petropoulos’ two books: Ο Τουρκικός Καφές εν Ελλάδι — “Turkish Coffee in Greece,” and Tο Άγιο Χασισάκι — “My Holy Hash.” Part tongue-in-cheek, part deadly serious, both books are both hilarious and devastating.

***3 Unfortunately, to build this palace of Neo-Ottoman kitsch that would make Davutoğlu proud, one of Greece’s classic old Xenia hotels, masterpieces of post-war Greek Modernism and most designed by architect Aris Konstantinidis, was torn down, and most of these hotels have suffered similar fates throughout the country, as the nationally run State Tourist Organization was forced to sell off its assets by the privatization forced on Greece then and to this day.

The Jiannena Xenia, above, built in the old wooded grove of Guraba, just above the center of town, and, below, perhaps Konstantinidis’ masterpiece, the Xenia at Paliouri in Chalkidike. (click)

Fortunately, Jiannena preserves one of Konstantinidis’ other masterpieces, its archaeological museum, below. (click)

****4 Ironically, the strudel that Croats and Slovenes imagine themselves eating in their Viennese wet dreams is probably a descendant of börek; and take it a step further: let’s not forget that croissants and all danish-type puff pastry items are known generically as viennoiserie in French. So the ancestor of some of the highest creations of Parisian/French/European baking arts is something that a Slovene says “nein danke” to in order to prove how European he is. Talk about the farcicalness of “nesting orientalisms.”

*****5 Of course, in every case, this assumption-cum-accusation, about the parasitic South draining the North of its resources, is patent bullshit. Southern Italy, the southern Republics of Yugoslavia, Castille, Galicia, Andalusia, and the southern tier of the European Union today, may get disproportionately more in the allotment of certain bureaucratic funds compared to the tangible wealth they produce. But they also provide the North, in every single one of these cases, with resources, labor and markets on which that North gets rich to a far more disproportionate degree and stunts the South’s growth in the process. So haydi kai…

It’s become a common-place — and not inaccurate — observation that the catastrophic economic pressure Germany is today exercising on the nations of Southern Europe for the sake of making some sick moral point is the fourth time it’s wrecked Europe in less than a century — the third time being when it decided, immediately upon reunification, to show the continent it was a political player again by practically single-handedly instigating the destruction of Yugoslavia.

******6

Over-oreganoed and over-lemoned — like much of Greek food — and overdone, over-salted and over-oiled, perhaps the only thing more repulsive than the soggy potatoes Old Greeks bake with lamb or chicken (though one horrible restaurant — which New Yorkers are for some reason crazy about: I mean like “take-the-N-train-out-to-Astoria-and-wait-for-a-table-for-an-hour” crazy — criminally serves them with grilled fish) is the serving of stewed meat with french fries. You’ve hit the rock bottom of Neo-Greek cuisine when you’ve had a dry, stringy “reddened” veal or lamb dish accompanied by what would otherwise be good, often hand-cut french fries, sitting limply on the side and sadly drowning in the red oil.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–

(click)

These are börek in Sarajevo being baked in a gastra, a strange piece of High Ottoman technology that is still used in much of northern Greece, especially Epiros and the rest of the Balkans, particularly the western parts: Albania, Montenegro (where uniquely in the Serb-speaking world, they call börek pitta like in Greek), Kosovo and southern Serbia — regions, interestingly enough, where börek is a particularly strong regional identity marker and the object of a powerful cult of affection and snobbery. Every and each börek in these parts is subjected to intense scrutiny; is there too much filling (major demerit points because you’re obviously trying to make up for the poor quality of your phyllo/yufka); is each layer fine enough, but able to both absorb serious quantities of butter and not get soggy, like a good croissant or a good paratha. Finally, that you use real — and good — butter, which makes almost all commercially sold varieties not worth trying, since using good butter on a commercial scale would make a börek that is prohibitively expensive, and especially in a country of culinary philistines like Greece, store-bought versions are almost inedible, as is most product in Turkey these days too, Turkish street food having suffered a marked decline in quality even as the tourist literature on the country continues to rave about it. But I have had good börek in Macedonia, in Mavrovo, and in Montenegro, in Žabljak, where the hotel made us a great cheese and a great cabbage one for a hike we went on. And in a high-end restaurant in Jiannena too; but next to me was an Albanian woman, who first smelled it, pricked at it with her fork, counting the layers of pastry, and then after a few minutes of just staring at it, pushed it away in disgust. Like I said, it’s an object of great snobbery. And forget Old Greece. It’s a standard rule of thumb that the further away in place and time a region of Greece is from the Ottoman experience, the exponentially worse the food gets. No one south of Larissa can bake a pitta to save their lives, or make a decent plate of pilav for that matter. Epiros is probably the only place you can still get a nice buttery mound of pilav — like the kind Turks make — with good yogurt. Southern Greeks seem allergic to rice, and have friggin’ potatoes with almost every meal. Maybe It’s a Bavarian thing — I dunno.

Reaaally good stuff, in Mavrovo, Macedonia (click) (See post: “Macedonia: Mavrovo, Dimitri and the Two Falcons“)

But everything baked tastes better in a gastra, the same root as the word for “womb” in Greek (or “gastritis”): rice and lamb, even zeytinyağlı vegetable dishes. It’s just incredibly tedious — and dangerous if you don’t know what you’re doing — to use. It’s a cast-iron dome, suspended with a very complicated chain mechanism over a stone platform. You first lift the dome and light your charcoal fire underneath it on the stone platform. When the fire has been reduced to hot embers, and the cast-iron dome has also gotten nice and hot, you brush the embers aside, position your tepsi of food, lower the hot cast-iron dome, and then pile the still glowing embers on top of the dome. Usually when they’ve cooled down completely the dish is done. The picture above shows gastras at all steps in the process.

I dunno really. Does it make that much of a difference? Everything is better when it tastes slightly smokey or when a little bit of ash has fallen into it — like Turkish coffee made in hot ashes. But it’s a ton of work and really impractical. If, for example, the embers go out completely and you raise the dome and the food isn’t done yet, you have to start the whole process from the beginning. Arthur Schwatrz, in his ever-best cookbook on Neapolitan food, Naples at Table: Cooking in Campania — which, like most good cookbooks these days, is as fantastic a source of history, anthropology and ethnography as it is of good recipes — says that a lot of foods legendary for how long you had to cook them for them to be the “real” article, like a Neapolitan ragù (pronounce with a double “r” and a “g” that sounds like a light Greek “gamma” – “γ”) that should take at least half a day to simmer or no self-respecting Neapolitan would eat it, were never really cooked that long. Rather, they were cooked on wood fires and braziers, which were constantly going out, had to be relit, while the sauce cooled off and took time to reheat, etc. Of course, for certain sauces and stews, and the fatty, sinewy cuts of meat we like in “our parts,” this kind of cooking is ideal. And not just the slow, long heat, but the cooling off and reheating especially.

(click)

It’s like that other piece of Ottoman high-tech (I don’t mean to make fun, but it wasn’t exactly their strong suit), the mangal home-heater or charcoal brazier. (above) You’d pile charcoal into it; leave it out in the street until the carbon monoxide burned off, then cover the embers with the lid and bring the whole incredibly dangerous, glowing — and often very large — brass behemoth inside to warm the house, or one hermetically sealed room really. Then, as my mother used to describe it, you’d get under the blankets or flokates, facing the mangal, so your face would turn all red and sweaty while your back was freezing, and hope you had fallen asleep before it started cooling off or that you had generated enough body heat under the blankets to last till morning. There were countless stories about families being found dead in the morning, because in the rush to bring this silly contraption into the freezing house, the carbon monoxide often hadn’t burnt off entirely and people would die from poisoning in their sleep. I can only imagine that their use was required because it was probably tricky to build chimneys in mostly wooden Ottoman urban housing — my mother only remembered them from Jiannena; in her village where the house was stone, there were regular stone fireplaces where you could keep adding wood because the chimney would let the smoke and gas escape — and I’m sure that many of the massive fires that consumed whole mahallades of Ottoman cities over the centuries and killed thousands on certain occasions, were probably caused by one accidentally knocked over mangal somewhere.

And whole neighborhoods would burn down and then be rebuilt in wood again, something I comment on in another post — “Macedonia: Sveti Jovan Bigorski“:

This is a kind of Ottoman tradition: build in wood, suffer repeated fires like the kind that wiped out whole districts of Istanbul throughout its history and killed tens of thousands. Then rebuild in wood again. It’s not known who said that the definition of neurosis is repeating the same action over and over and expecting a different result, but it also might be the definition of stupidity. Only after a fire destroyed two thirds of Pera in 1870 in just six hours did people in those predominantly Christian and Jewish areas start building in masonry, which is why those neighborhoods are architecturally far older today than those of the now ugly two-thousand-year-old city on the original peninsula, where there is almost no old domestic architecture left (except, again, in former minority neighborhoods, for some reason, like Fanari or Balata or Samatya).

More on the symbolics of börek and the break-up of Yugoslavia in the next post.

–

Comment: nikobakos@gmail.com

–